Napier was one of the most sought after coaches last offseason after turning the Ragin' Cajuns into a well-oiled machine.

LAFAYETTE, La.—Sure, Billy Napier says while leaning away from his desk and glaring across the other side, he thought about leaving Louisiana for another head coaching job last offseason.

Who can really blame him? When you’re the coach at a Sun Belt program making six figures and a major conference school engages you with a gift basket of goodies—quadrupled salary, double staff pay pool, sparkling facilities, a massive donor base—you at least peak into the basket.

Napier peaked. He thought, he prayed and he sought advice from mentors within the profession. Of all the reasons he remained here—he and his family enjoy living in Lafayette, for one, and secondly, his goal of claiming a conference title hasn’t been achieved—there is one that rose above the rest: He knew he’d have a good team in 2020, maybe his best team yet.

“I kept thinking about coaching another team,” he says, “and the one team I could get excited about coaching was this team here that we got coming back. This job’s not done.”

Seven months after that interview and 10 months after spurning that wave of job inquiries, Napier has the 2020 Ragin’ Cajuns at 3–0. They opened the season by knocking off Iowa State and cracked the top 25 for the first time at the school since the 1940s. They’ve got an NFL prospect at nose tackle, two more pro-caliber players at running back and an offensive tackle generating NFL interest too.

They’ve been far from perfect, of course. Like many teams this year, the Cajuns battled a host of COVID-related issues (more than a half-dozen starters missed one game), and they needed two last-second escapes against Georgia Southern (a 53-yard field goal as time expired) and Georgia State (a win in overtime) to get here undefeated.

On Wednesday night, in front of a nationally televised audience on ESPN, Napier’s team meets fellow Sun Belt unbeaten Coastal Carolina (3–0), a clash of two teams that have both toppled Big 12 programs (Coastal beat Kansas in its opener). The game has been rescheduled two times within two weeks—the first for COVID-related issues at Appalachian State and the second for Hurricane Delta, which roared ashore last Friday, causing only minimal damage to Louisiana’s campus, thankfully.

The UL athletic department didn’t need anymore adversity. Starting in January 2019, the school has experienced a disturbing string of unrelated deaths. Six members of the athletic department have unexpectedly died, many of them from heart-related issues. The most recent came in August, when 31-year-old offensive line coach D.J. Looney collapsed and died from a heart attack during a camp practice.

It was the sixth passing in about 19 months. Geri Ann Glasco, 24, the head softball coach’s daughter and a volunteer assistant, was involved in a fatal, five-car pileup on I-10 just east of Lafayette. Leonard Wiltz, a longtime UL groundskeeper, and Lynn Williams, the UL equipment manager, both passed during the same week in March last year. Mastern “Saint” Julien Jr., the department’s bus driver, died at age 68 that June, and Tony Robichaux, the winningest head baseball coach in school history who still presided over the program, succumbed to a heart attack that July at age 57.

“It was horrific,” says Bryan Maggard, the school’s athletic director. “You had these bombardments. At some point, part of the moniker here was ‘Who’s next? What’s next?’”

The most recent death hit the football program hardest. A bubbly, infectious person, Looney has been part of the team since Napier took over in 2018, helping a program battle back from NCAA probation by achieving what many thought to be improbable: advancing to the conference championship game the first two seasons and winning a school-record 11 games last year.

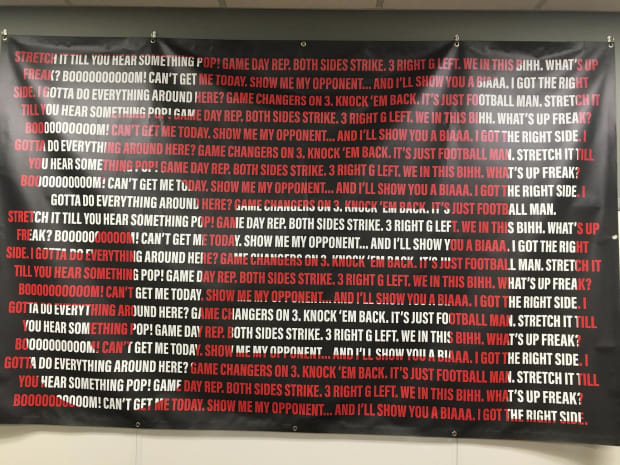

In the team’s offensive line meeting room, a poster stretches across one wall portraying quotes often used by Looney. Rob Sale, the program’s offensive coordinator, emotionally gestures toward the wall art, reading off a few Looney-isms.

We in this bihhh!

Can’t get me today!

I gotta do everything around here?!

Stretch it till you hear something pop!

“It hit me hard,” Sale says.

Looney was a key piece of a well-oiled machine that Napier has created here by using a specific model: the Bama Way. Napier, 41, spent six seasons on Alabama’s staff, one in 2011 as an analyst and five in 2013–17 as receivers coach. He says Saban “picked him up off the streets” after Dabo Swinney fired him from his position as offensive coordinator at Clemson in 2010.

Over the next half-decade, Napier watched, learned and assisted in one of the greatest dynasties in college football history. His UL program is a smaller version of the one in Tuscaloosa. His on-field and support staff includes a half-dozen people from the Saban lineage. Sale, himself a former strength coach for Saban, describes the Cajuns as having the “Alabama backbone.”

With Maggard’s blessing, Napier grew the UL support staff by 75%, created a snack budget of $1.5 million and increased the assistant salary pool by 40%. He developed a thriving, 50-player walk-on group called “The Heartbeat,” which affords the team more bodies to practice like Saban does, using what he calls “2-spotting,” the art of splitting the team into four squads (the 1s, 2s, 3s and rookies) and holding two scrimmages simultaneously on adjacent fields.

While his program resembles a bite-sized version of Saban’s, Napier isn’t like his mentor. He’s “chill,” players and assistants say, a laid-back country boy who speaks softly and slowly, the son of a football-coaching family whose roots are in the hills of north Georgia.

Mark Hocke, UL’s strength coach and another Saban disciple, describes Napier another way.

“He’s just different,” says Hocke.

Maybe that explains why he’s still here. One of the most sought-after coaches last cycle, Napier fielded interest from a bevy of programs. Napier isn’t one to discuss such things. He declines to speak about specific schools and gives only brief answers when asked about last offseason.

Industry sources say Napier fielded interest from Ole Miss during the early portion of the hiring cycle, when he was preparing his team to play in the Sun Belt championship game. Buried in game work, he declined to speak with representatives until after the game (by then, the Rebels hired Lane Kiffin). Missouri inquired into Napier’s interest as well ahead of the Sun Belt championship game, before hiring Eli Drinkwitz.

Later in the hiring cycle, Mississippi State and Baylor expressed more serious interest in Napier. In fact, the coach interviewed with Baylor officials in New Orleans the week of the national championship game. He learned then about NCAA sanctions that the Bears were expecting to receive—a turnoff.

Through it all, Maggard wasn’t too worried.

“I had some inside information about how... some jobs he wasn’t interested in. I felt like there was mutual interest [in one],” Maggard says without expounding. “It’s not like I was not expecting him to be a hot candidate. It’s constantly on your mind.”

Napier’s staff, meanwhile, kept “the blinders on,” says Hocke. “A lot of people were calling and texting, ‘What’s going on!?’”

Baylor eventually hired then-LSU defensive coordinator Dave Aranda. Mississippi State eventually hired Washington State coach Mike Leach, who signed a contract paying him $5 million a year—five times that of Napier’s salary.

“When you coach, it goes back to the root of what’s life about and what’s your purpose here,” Napier says. “I got into coaching because my dad was a high school football coach. I didn’t choose the profession because I was going to be on the cover of a magazine and make a lot of money.”

That said, Napier changed sports agents this offseason, choosing as his representative one of the country’s most powerful college coaching operatives, Jimmy Sexton and his firm, CAA.

Maggard believes he can keep his coach in Lafayette for at least the next several years with even more of a financial commitment to the program. For example, Louisiana is soon starting a capital campaign to go toward a $65 million stadium renovation. And while the program gave Napier a two-year extension and raise in January, Maggard hopes to make it even more in the future. Napier will make a base salary of $880,000 this year in a deal escalating to $950,000 in its final year, 2025.

Maggard views the football program as the front porch of a university that needs to expand.

“I think we have found the guy, and we need to invest millions in him,” says Maggard, a longtime Missouri athletic administrator before landing at UL in 2017. “I believe there is a correlation between a successful football program and enrollment growth at the university.”

The pandemic may impact Napier’s tenure at the school. The bizarre, shortened season coupled with the financial strains on athletic departments is expected to produce one of the slowest coaching cycles in modern history.

Napier’s decisions last offseason already show that he’s selective with his next move, his focus on landing at a blueblood program with the resources and history to compete for a conference championship and national title. However, the leap from Group of Five head coach to a football powerhouse is somewhat rare.

Over the last seven hiring cycles, there have been 15 openings at what many in college football would refer to as a blueblood program (the top 13 in athletic budgets plus USC, a private school). Only four of the 15 were filled by Group of Five head coaches, and two of them had close connections to the school: Mike Norvell (Memphis to Florida State, 2019), Tom Herman (Houston to Texas, 2016), Jim McElwain (Colorado State to Florida, 2014) and Charlie Strong (Louisville to Texas, 2013). The other 11 openings went to assistants at the Power 5 level (4), Power 5 head coaches (6) or NFL coaches (1).

Napier, though, isn’t focused on any of this. After all, he’s got more to accomplish here—and it starts Wednesday in a Sun Belt showdown against Coastal Carolina.

“One thing I’ve learned over time, in just two short years as a head coach,” Napier says, “is ultimately you’ve got to have passion for the next challenge and next team you’re going to coach.”

For Napier, that is the 2020 Cajuns.