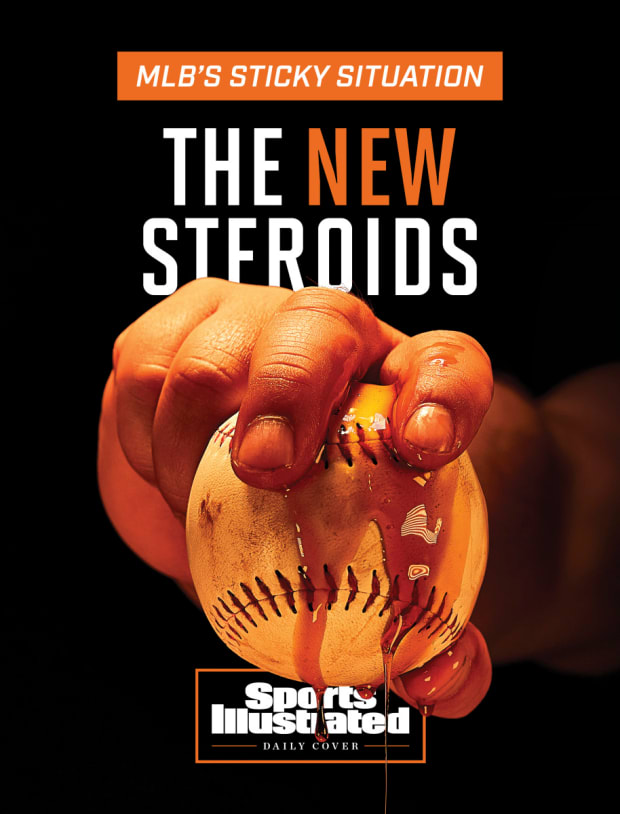

The inside story of how rampant pitch-doctoring in MLB is pumping pitchers up and deflating offenses.

To understand the fiasco of baseball’s 2021 season, which people around the game describe as sullied by rampant cheating to a degree not seen since the steroid era, all you have to do is pick up a ball.

Then try to put it back down.

One ball made its way into an NL dugout last week, where players took turns touching a palm to the sticky material coating it and lifting the baseball, adhered to their hand, into the air. Another one, corralled in a different NL dugout, had clear-enough fingerprints indented in the goo that opponents could mimic the pitcher’s grip. A third one, also in the NL, was so sticky that when an opponent tried to pull the glue off, three inches of seams came off with it.

Over the past two or three years, pitchers’ illegal application to the ball of what they call “sticky stuff”—at first a mixture of sunscreen and rosin, now various forms of glue—has become so pervasive that one recently retired hurler estimates “80 to 90%” of pitchers are using it in some capacity. The sticky stuff helps increase spin on pitches, which in turn increases their movement, making them more difficult to hit. That’s contributed to an offensive crisis that has seen the league-wide batting average plummet to a historically inept .236. (Sports Illustrated spoke with more than two dozen people; most of them requested anonymity to discuss cheating within their own organizations.)

From the dugout, players and coaches shake their heads as they listen to pitchers’ deliveries. “You can hear the friction,” says an American League manager. The recently retired pitcher likens it to the sound of ripping off a Band-Aid. A major league team executive says his players have examined foul balls and found the MLB logo torn straight off the leather.

In many clubhouses across the sport, the training room has become the scene of the crime: Pitchers head in there before games to swipe tongue depressors, which they use to apply their sticky stuff to wherever they choose to hide it, then return afterward to grab rubbing alcohol to dissolve the residue. Even that is not always sufficient. One National League journeyman reliever, who says he uses Pelican Grip Dip, a pine tar/rosin blend typically used by hitters to help grip their bats, has been flagged at airport security.

“They swab my fingers—and this is after showering and everything—and they’re like, ‘Hey, you have explosives on your fingers,’ ” he says. “I’m like, ‘Well, I don’t, but I’m sure that I have something that’s not organic on there.’ ”

The MLB rule book bars pitchers from applying foreign substances to baseballs, but officials have so far done little to curb the practice. (MLB declined to comment but says it is focused on the issue.) Meanwhile, as high-speed cameras and granular data have made it clear that doctoring the ball makes it almost impossible to hit, baseball has found itself dripping with sticky stuff.

“This should be the biggest scandal in sports,” says another major league team executive.

As MLB dawdles, and batting averages dwindle, the use of substances has become all but institutionalized. One NL reliever, who says he does not apply anything to the baseball because sticky stuff disrupts the feel of his sinker, says his pitching coach suggested this year that he try it. An AL reliever, who says he uses a mixture of sunscreen and rosin, recalls a spring-training meeting in 2019 in which the team’s pitching coach told the group, “A lot of people around the league are using sticky stuff to make their fastballs have more lift. And if you’re not using it, you should consider it, because you’re kind of behind.” The clubhouse attendants of at least one minor league team, according to a player, stock cans of Tyrus Sticky Grip, another product intended to keep hitters from accidentally flinging their bats, and distribute them to pitchers who ask. The NL reliever who uses Pelican says he played for a team that hired a chemist—away from another club—whose duties include developing sticky stuff.

An SI analysis of Statcast data suggests that one team in particular leads the industry in spin: the defending world champion Los Angeles Dodgers.

According to the data, L.A. has by a large margin the highest year-to-year increase of any club in spin rate on four-seam fastballs, which are considered a bellwether pitch. In fact, the Dodgers’ four-seam spin rate is higher than that of any other team in the Statcast era. There is no proof the Dodgers are doctoring baseballs, but nearly across the board, their hurlers’ spin rates on that pitch have increased this season from last.

The Dodgers declined to comment.

Souped-up spin exists far beyond L.A., though. Across the league, some pitchers hide gunk on the brim of their cap, in their jockstrap, on their shoelaces. But most no longer bother to be so crafty. Turn on almost any baseball game these days and you can see a pitcher digging into his glove between pitches, coating the ball with his preferred concoction.

“It’s so blatant,” says the AL manager. “It’s a big f--- you. Like, what are you gonna do about it?”

Never in the history of Major League Baseball has it been so hard to hit the ball. The league batting average would be the worst full-season number of all time. Nearly a quarter of batters have struck out, which would also be the feeblest performance ever. The AL manager recently admitted to himself before a game that he expected his team to whiff a dozen times. One of the team executives says that against some pitchers, he is proud of his hitters for just making contact.

MLB introduced a new baseball this year, one that was designed to increase offense but seems instead to be suppressing it. (Baseball Prospectus found that the new ball, which is about 1% lighter than the old one, is spinning faster, making it harder to hit, and flying less far once struck.) Many hitters are still ramping up from a truncated 2020 season. After a year with the universal designated hitter, pitchers are back at the plate, dragging down numbers. All these factors contribute to the drought. But mostly, people around the game blame sticky stuff.

“If you want to talk about getting balls in play and kind of readjusting the balance of pitching and offense, I think it’s a huge place to start,” says an NL reliever who says he does not apply anything to the baseball because he believes that is cheating. “Because it seems to have created these basically impossible-to-hit pitches.”

Initially, pitchers mostly sought grip enhancements. Brand-new major league baseballs are so slick that umpire attendants are tasked with rubbing them before games with special mud from a secret spot along a tributary of the Delaware River. Pitchers also have access to a bag of rosin, made from fir-tree sap, that lies behind the mound. Hitters generally approve of this level of substance use; a pitcher who cannot grip the baseball is more likely to fire it accidentally at a batter’s skull.

But it has slowly, and then quickly, become clear that especially sticky baseballs are also especially hard to hit. For more than a decade, pitchers have coated their arms in Bull Frog spray-on sunscreen, then mixed that with rosin to produce adhesive. They have applied hair gel, then run their fingers through their manes. They have brewed concoctions of pine tar and Manny Mota grip stick (essentially, pine tar in solid form), which are legal for hitters trying to grasp the bat. A lawsuit brought late last year by a fired Angels clubhouse employee alleged that the Yankees’ Gerrit Cole, the Nationals’ Max Scherzer and the Astros’ Justin Verlander were among the users of one such substance. (The suit has been dismissed and is being appealed; SI reached out to each player through his agency but did not receive replies.)

More recently, pitchers have begun experimenting with drumstick resin and surfboard wax. They use Tyrus Sticky Grip, Firm Grip spray, Pelican Grip Dip stick and Spider Tack, a glue intended for use in World’s Strongest Man competitions and whose advertisements show someone using it to lift a cinder block with his palm. Some combine several of those to create their own, more sophisticated substances. They use Edgertronic high-speed cameras and TrackMan and Rapsodo pitch-tracking devices to see which one works best. Many of them spent their pandemic lockdown time perfecting their gunk.

“Guys have been using stuff for years,” says Marlins rightfielder Adam Duvall, “But I think recently it’s almost become an art. Guys are getting really good at it.”

Experts do not entirely understand why sticky stuff works so well, but they agree that it does. The addition of any substance to the surface of an otherwise mostly smooth projectile will make it behave unpredictably—Gaylord Perry’s spitball helped get him to the Hall of Fame—but tackier products have even more promise. For one, says one of the NL relievers, gluing the ball to your hand gives you more control over when and how you release it.

“I think that a good portion of the increased velocity is because guys can throw pitches at 100% all the time,” he says. “They can rear back and literally throw with everything they've got and still have a reasonable amount of control because of the sticky stuff. I think if the ball feels a little slick, your mechanics have got to be a little better; you’ve got to stay within your means a little bit more.”

But the biggest benefit of using sticky stuff is the way it contributes to spin. The faster a baseball spins, the more potential for movement it has. And movement is what makes a baseball so hard to hit. If a pitcher can harness that added spin, he can make his fastball appear to rise as it reaches home plate, so the hitter swings under it.

One way to increase spin rate is to increase velocity. Another is to apply shear force to the ball, probably by adjusting finger strength. It is possible to make modest gains, especially on breaking pitches, through improving the efficiency of a pitcher’s grip and delivery. But the most effective means is to produce friction, and the best way to do that is to smear gunk on the ball.

“You can just create and leverage [friction] better if you have some sort of a substance, whether that’s legal or illegal,” says a pitching expert who works for an independent facility and also consults for an MLB team. “So guys are chasing, yes, more spin, but it’s not the raw spin itself that’s making the pitch better. It’s what that raw spin affords, which is more total movement, potentially.”

For hitters, all this suddenly acquired extra movement is catastrophic. What was an elite spin rate in 2018 is now average. The added spin means that the average four-seam fastball drops nearly two inches fewer this year than it did in ’18, according to Statcast, making it appear to hitters as if it’s rising. So far in ’21, facing fastballs down the middle thrown at 2,499 revolutions per minute or fewer, hitters have batted .330. Facing fastballs down the middle thrown at 2,500 rpms or more, they have batted .285. And the percentage of high-spin fastballs has increased threefold since ’15.

“I’m tired of hearing people say that players only want to hit home runs,” says Rockies rightfielder Charlie Blackmon. “That’s not why people are striking out. They’re striking out because guys are throwing 97 mile-an-hour super sinkers, or balls that just go straight up with all this sticky stuff and the new-baseball spin rate. That’s why guys are striking out, because it’s really hard not to strike out.”

Hitters spend their entire careers building a library of pitches, explains Garrett Beatty, who teaches physiology and applied kinesiology with a focus on sports at the University of Florida. Because they have only 200 to 400 milliseconds—about the blink of an eye—to decide whether and where to swing, they have to extrapolate where the pitch will end up, based on all the pitches they have seen in their lifetimes.

“There’s some [pitchers] where, if you swing where your eyes tell you, you won’t hit the ball, even if you’re on time,” Blackmon says. “I have to go out there and if my eyes tell me it’s in one place, I have to swing to a different place. Which is hard to do. It’s hard to swing and try and miss the ball. But there’s some guys where you have to do it, because their ball and the spin rate or whatever is defying every pitch that you’ve seen come in over the course of your career. … I basically have to not trust my eyes that the pitch is going to finish where I think it’s going to finish and swing in a different place, because the ball is doing something it has no business doing.”

Hitters are bothered on a mechanical level. They are bothered on a moral one, too.

“It is frustrating because there’s rules in this game,” says Duvall. “I feel like I’ve always been a guy that’s played by them, and I expect that of others, too.”

Before his career ended in infamy amid the Black Sox scandal, Eddie Cicotte baffled opponents throughout the early 20th century with his signature “shine ball,” coating it with talcum powder that he’d poured in his pants pocket; decades later, in addition to saliva, Perry lubed up with Vaseline and K-Y Jelly. But only a handful of hurlers have ever been caught in the act and punished, most recently when relievers Will Smith (of the Brewers) and Brian Matsuz (Orioles) were ejected and handed eight-game suspensions, less than one week apart, in May 2015. Last week, when umpire Joe West noticed a mark on the brim of Cardinals reliever Giovanny Gallegos’s cap, he confiscated the hat but left the pitcher in the game.

If players have been doctoring the ball for a century, why is this all coming to a head now? Nearly everyone interviewed for this story mentioned one person in particular: Dodgers righthander Trevor Bauer.

In 2018, Bauer seemed to accuse the Astros of applying foreign substances to baseballs in a cryptic tweet replying to a comment about Houston’s rotation. “If only there was just a really quick way to increase spin rate,” he wrote. “Like what if you could trade for a player knowing that you could bump his spin rate a couple hundred rpm overnight...imagine the steals you could get on the trade market! If only that existed…” (Houston denied the allegation.) He complained to reporters that by ignoring the problem, the league was sanctioning illegal behavior.

Bauer said he had done tests in a pitching lab and found that sticky stuff added about 300 rpm to his four-seam fastball. He wrote in a Players’ Tribune essay that after eight years of trying, “I haven’t found any other way [to increase spin rate] except using foreign substances.”

He also tried to make his point on the field: He used Pelican in the first inning of a 2018 start and watched his four-seamer, which usually averaged about 2,300 rpm, tick up to 2,600 rpm. After the first inning, that number dropped back to normal.

“If I used that s---, I’d be the best pitcher in the big leagues,” he told SI in 2019. “I’d be unhittable. But I have morals.”

From March through August of that year, his four-seamer averaged 2,358 rpm, according to Statcast. In September, it jumped to 2,750. In 2020, when he won the Cy Young Award for the Reds, it was 2,779. This season, the first of a three-year, $102 million deal that makes him the highest-paid pitcher in history, it’s 2,835.

Before Bauer’s spin rate jumped, he had an ERA of 4.04 and the 228th-best opponent batting average, at .241. Since the increase, those figures are 2.31 and an MLB-best .161. The Athletic reported in April that the league had collected several balls from Bauer’s first start that “had visible markings and were sticky.” Asked about the report at the time, Bauer said, “MLB is just collecting baseballs to do a study. Like, they’re not doing anything with them. No one’s under investigation, or no one’s—like, just these gossip bloggers out here, writing stuff to try to throw water on my name or whatever.” (The league is indeed collecting balls from every pitcher for analysis, and there has been no finding that Bauer did anything wrong.)

Through both his agent and the team, Bauer declined to make himself available for an interview. Manager Dave Roberts says he does not know if his players use sticky stuff.

Los Angeles this year is Spin City, according to the SI analysis. In March, the league sent a memo to teams to warn them that it would begin studying the problem, collecting those baseballs for analysis and using spin rate data to identify potential users of foreign substances. Officials have focused on four-seam spin rate, because breaking pitches can sometimes be enhanced naturally. But four-seamers are thrown with the hand and wrist behind the ball and with true north-south backspin, so there are fewer variables.

SI found that through June 2, the Dodgers had the highest increase in year-to-year four-seam spin rate, at 7.01%. The next highest was 4.21%, by the White Sox. That increase and that gap are enormous. The Red Sox came in third, at 4.01%; the Nationals fourth, at 3.07%; and the Yankees fifth, at 2.94%. The league-average increase has been 0.52% this year. (All clubs declined or did not respond to requests for comment.)

Some of this surely relates to personnel. L.A., for instance, traded away Dylan Floro and Adam Kolarek and did not re-sign Pedro Baéz, all low-spin pitchers. They signed Bauer and Jimmy Nelson and traded for Garrett Cleavinger and Alex Vesia, who all spin the ball. Still, every active Dodger pitcher except one has a higher spin rate than he did last year.

L.A.’s four-seam spin rate is 97 rpm higher than that of any other team in the Statcast era. The 2020 Reds, Bauer’s former team, and a group that calls itself Spincinnati—because of their development of pitchers with high spin rates—rank second. (When SI asked for an interview with a Cincinnati pitcher about sticky stuff, longtime Reds PR chief Rob Butcher refused to make the request to the player. “I am not asking him to participate in your project,” Butcher wrote in an email.)

Whether or not Bauer is using sticky stuff, other players around the league have taken note of his success and have begun experimenting. In 2018, Bauer compared the use of foreign substances to that of steroids: MLB looks the other way while those unwilling to cheat put themselves at a disadvantage. Other people in the sport echo him.

“People need to understand the significance of spin,” says one of the team executives. “It is every bit as advantageous as a [performance-enhancing drug]—except it has been sanctioned by the league and there are no [harmful] consequences for your body.”

“We’re just doing the same thing we did during the steroid era,” says the other team executive. “We were oohing and ahhing at 500-plus-foot home runs. ... A 101-mile-an-hour, 3,000-rpm cutter, isn’t that the same thing as a 500-foot home run? It’s unnatural.”

“It’s like steroids,” says one of the NL relievers. “For us that refuse to use sticky [stuff], we get pushed out, because ‘you don’t have great spin rate.’ Well, no s---, because I don’t cheat.”

The tacit approval leaves everyone doing difficult moral math. At the moment, umpires generally rely on managers to request that they check a pitcher. Managers largely refuse to do so, in part because they know their own pitchers are just as guilty, and in part because they worry their team may someday acquire the pitcher in question. Executives and coaches who personally abhor the practice do not see much benefit in telling their own pitchers to knock it off, knowing that will accomplish little more than losing games and angering their employees. Fringe pitchers tell themselves that everyone is doing it—indeed, that the league’s clumsy management of the game all but requires it.

“MLB has been changing the balls for so many years now and it’s so inconsistent with how they’re rubbed up and what the seams feel like and how stretched the leather is and everything,” says an NL reliever who says he uses a mix of pine tar, Mota stick and rosin. “The only thing that's consistent is what we put on our fingers.”

And they understand that they are being evaluated in an environment in which everyone else is using it. Four minor leaguers have so far this season been caught with substances, ejected and suspended for 10 games. (After one of those incidents, says a player who was there, relievers on both teams headed to the clubhouse to switch out their gloves.) Those punishments are supposed to send a message, but players hear a louder one.

“The calculus is whoever gets outs better gets to play major league baseball,” says the NL reliever who says he uses Pelican. “There’s some guys that might have a moral dilemma about it, but I’m not one of those guys. It's not bad for your health. Steroids ... could kill you. That’s different than washing your hands of stick at the end of the game.”

Meanwhile, the league is weighing rule changes designed to increase offense. The minor leagues have begun experimenting with larger bases, a ban on infield shifts and a limit on pickoffs. If any of these show promise, the majors could adopt them.

“They talk about rule changes,” says one of the team executives. “I think people would be absolutely shocked if they actually enforced this, how much you’ll start to normalize things without rule changes.”

Bauer has in the past suggested that the league legalize everything, and there is merit to that approach: Many of these substances are hard to police. But legalizing everything would only make pitchers even more dominant and the game even less watchable.

Most other people around the sport want the Spider Tack gone. Rawlings, which produces MLB baseballs, has experimented for years with a precoated ball such as the ones used in Japan and South Korea. MLB has sent prototypes to a handful of teams in spring training over the years; they reported that the tack wore away too quickly. That process is ongoing. Some pitchers propose a universal substance, developed and distributed by MLB, much the way rosin is.

The AL manager suggests a TSA-style screening in the bullpen, then a 10-game suspension for anyone caught with anything afterward. One of the team executives supports suspending skippers for their players’ infractions. Managers generally did not make enough money as players to retire comfortably; pulling their game checks, he says, would turn them into hall monitors. Several players bring up the idea of escalating suspensions for pitchers. “At some point,” says the first NL reliever, “you should just get kicked out of the [league].”

People familiar with the league’s plans say that stepped-up enforcement is forthcoming—despite some teams’ attempts at subterfuge. Once baseballs are out of play, they are supposed to be thrown into the home dugout, where they can be collected by MLB for analysis. Some teams, observers note, have tried tossing especially sticky balls into the visitors’ dugout. Meanwhile, league officials plan to begin punishing offenders. Days or weeks from now, they will encourage teams to police their clubhouses, then instruct umpires to start checking pitchers more frequently. Offenders are to be ejected and suspended 10 games.

“Pitchers are shortsighted if they’re not mad [about sticky stuff],” says Marlins reliever Richard Bleier, who says he has never used anything more than sunscreen and rosin because he wants to feel proud of his career. “Like, ‘Oh, we don’t want hitters to hit’—well, look what’s happening now. Hitters aren’t hitting, and now everybody’s going to be penalized.”

Not everyone agrees. Three minor league pitchers tell SI they use sticky stuff and they don’t feel guilty about it. “We’re all trying to make the big leagues, and if that’s what it takes to get there, that’s what it takes,” says one. “They want the guys with the best stuff, and the guys with the best stuff are using something.” So he digs his fingers into his team-issued can of Tyrus, and he heads to the mound.

Additional research by Dan Falkenheim.

• How the L.A. '84 Olympics Changed Everything

• At the Indy 500, Roger Penske Is Still Running Circles Around Everyone

• The Mental Peril of This NBA Season

• Police Killed George Floyd. An MMA Fighter Punched Back