Tony Rodriguez did not, ultimately, save Tina Tintor—and that haunts him to this day.

The man walks into a Las Vegas Starbucks and his hands speak first. They are small and rough and soiled, with used-sandpaper skin and nails nubbed down by an uneasy life. You can read so much from a person’s hands, and Tony Rodriguez’s hands tell the story of a troubled journey.

Or, put differently: There is no joy to the 47-year-old sitting here. Not as a medium black coffee is placed before him, not as he talks about shared geography and athletic glory days. Some folks walk the earth with a pep in their step. Others come to believe they are cursed.

Tony Rodriguez does not use that word, cursed. But there are certainly times when he wonders how, exactly, it all came to this: his past life dealing drugs along the Vegas Strip, his three years and counting addicted to heroin and meth, his long nights sleeping inside tunnels and on park benches, his hunger, his anxiousness, his waywardness.

Eric Jamison/AP

Rodriguez says he makes money today largely by sneaking onto construction sites, stealing copper wiring, stripping it down and then selling it. Some of the earnings go toward food and rent. Much goes to the heroin that he and his girlfriend, Brittany, shoot into their arms at least once every day. He is not proud of any of this. “I don’t like that I steal,” he says. “I would never hurt anyone. I just… .”

Rodriguez wraps the stubby fingers of his right hand around his coffee cup. He takes dainty sips through a bushy salt-and-pepper goatee. It is a frigid February morning, and the Starbucks door swings open with every cold gust of wind. The chill bothers most customers; they shiver and tug extra tightly at sweatshirts and jackets. But not Rodriguez. He is numb to the discomforts that disturb most of us. “To me,” he says, “they don’t exist.”

Last fall, though, something happened that would haunt even Tony Rodriguez.

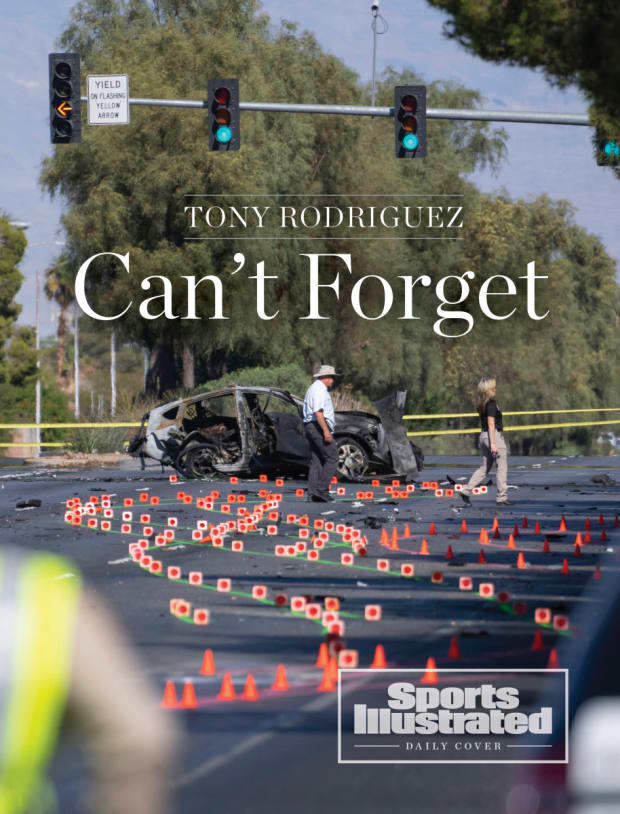

You can still see the burn marks.

They’re not as obvious now as they were a few months back; certainly not as pronounced as in the early morning hours of Nov. 2, 2021, when flames exploded from a Toyota RAV4 and onto the surface of South Rainbow Boulevard, a few miles off the Strip. But if you look closely, you’ll spot the discolored indentation, the blending of blacks and grays and charcoals onto the otherwise smooth pavement.

You’ll see where two lives forever changed.

When Henry Ruggs III, a 22-year-old wide receiver for the Raiders, allegedly drank too many mai tais and then raced his Corvette Stingray at an estimated 156 mph, his actions did not occur within a vacuum. In the passenger seat sat Kiara Kilgo-Washington, his longtime girlfriend and the mother of his one-year-old daughter. And on the road before them, driving within the speed limit, was 23-year-old Tina Tintor, with her golden retriever, Max, in the passenger seat.

Ruggs had been a first-round pick only a year earlier, a national champion at Alabama who used his athletic gifts to rise from a modest upbringing in Montgomery, Ala., to a $16 million contract.

Tintor, by contrast, lived with her brother and parents, first-generation Croatian immigrants, in a small white home five miles off the Strip. Before leaving to pursue a career in computer programming she’d worked as a clerk at Target.

In the early morning hours before Ruggs drove home drunk, Tintor was at a park with Max and a friend. She left to head home around 3:35, right around the time that Ruggs—whose blood was later measured at twice the legal alcohol limit—pressed hard on the accelerator. According to police, Ruggs’s Corvette was soaring down the middle of a three-lane street when it swerved into the far right lane. According to a statement from Kilgo-Washington, Ruggs looked up, saw the rear of Tintor’s slow-moving SUV and screamed, “What is this guy doing?!”

It was too late. Ruggs slammed on the brakes, but the front of his car collided with Tintor’s at 127 mph, the impact turning the Corvette into a crumpled tin can as it spun around and around for some 500 feet before coming to a rest near a stone wall. The Raiders’ receiver, not wearing a safety belt, was halfway ejected, his body left dangling from the vehicle.

The RAV4, meanwhile, rocketed nearly 600 feet down the northbound lanes of Rainbow Boulevard before bursting into flames.

Tony Rodriguez has seen death before.

He wants to make this clear. Just so there’s no confusion. “I’m not new to it,” he says. “Wish I were. But I’m not.”

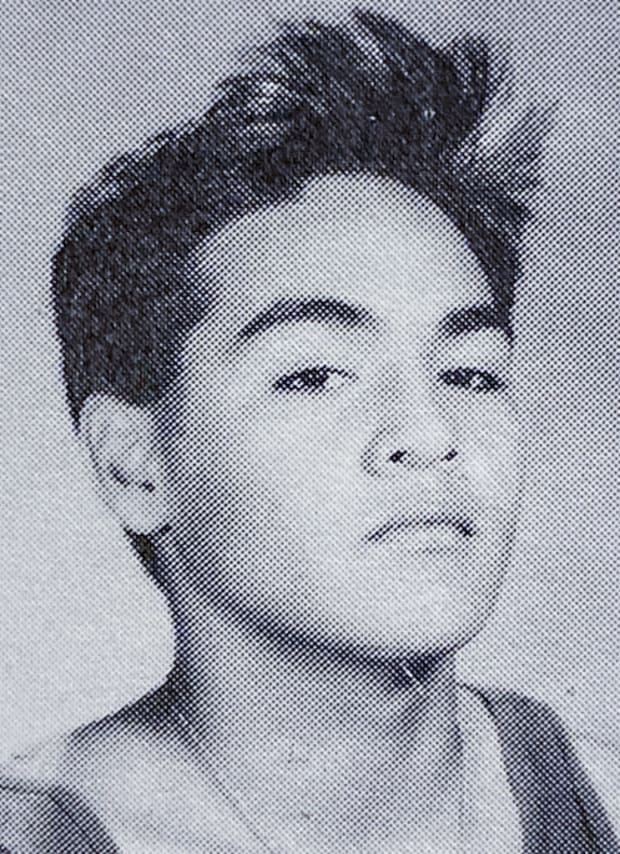

Rodriguez grew up in a small home in East Los Angeles, one of five children raised by Erlinda Vega, a social worker and single mother. The family was poor, and Tony was always in and out of trouble—fights, skipping school, some gang activity. “He was a super hyper kid,” says one older sister, Francine Telles.

For a brief period, young Tony found salvation in sports. He played on the JV football team at Mark Keppel High and as a sophomore caught on as a backup catcher with the varsity baseball squad. The Aztecs had a star pitcher-shortstop named Keith Walters, and Tony thought that scouts coming to see Walters might notice him, too. But “that was probably unrealistic,” says Walters (who never played college sports and recently wrapped a lengthy military career). “Tony had a strong arm but horrible footwork. He was a raw hitter, completely fundamentally unsound. But, boy, he could hit the ball a long way.”

Ultimately, Rodriguez was kicked off the baseball team because of his grades and attendance, and as a junior he dropped out of school. He worked for a short period at Disneyland, but the L.A.-to-Anaheim commute ate up his time and gas money. That led him, at 18, to Metro First Call, a service used by morgues and mortuaries to retrieve dead bodies.

Rodriguez would get his assignments, fire up his Ford Aerostar and head off to collect the deceased. “I’ll never forget my first one: Harold Miner, from Arkansas,” he says. “He was tall, maybe 6’ 7”. And his feet hung over the gurney.”

Every day Rodriguez looked death straight in the eye. From stillborns (“I’d always put a sheet over them”) to seniors, he drove hundreds of hours alongside the lifeless, the hum of a car radio providing the lone connection to humanity. “He’d always wanna tell me all the things he saw,” says Francine. “I was always like, ‘Tony, please. I don’t need to hear about the dead bodies.’”

Courtesy of Jeff Pearlman

One day in the mid-1990s, a mortuary director asked Rodriguez to go fetch the body of someone who shared the same last name: Larry Rodriguez. “Your brother,” the director joked. Haha.

As tended to be the case, the director shared with Rodriguez a little background information: This person, a felony arsonist, had died by suicide while serving time at Solano State Prison, a good six hours up the coast.

“And it really freaked me out,” Rodriguez recalls, “because it actually was my brother.”

He says his boss at Metro First urged him not to take the assignment, but he felt the pull of family. Rodriguez drove the six hours to Solano County, stared at his lifeless sibling, shed some tears, then loaded the corpse into his vehicle and ferried it away.

“I wanted to bring Larry back home,” Rodriguez says, decades later. “It needed to be me. He was family.”

The burden of that job outweighed any financial benefits, and over the next two decades Rodriguez bounced from gig to gig and city to city—some more time in Los Angeles, several years running gas stations in St. Louis, and finally, 15 or so years ago, a permanent move to Vegas, near Francine. Tony liked the city and he spent a number of years rigging for stage shows around town. Ultimately, though, he found there was far better money to be made bouncing from casino to casino, peddling crystal meth. “Eight hours a day, all I did was sell drugs,” he says. “We would start at Mandalay Bay, drive all the way down the boulevard and stop at every casino, making deals.”

It was all going smoothly—as smoothly as possible, considering the circumstances—until Rodriguez started using meth himself. “It’s the worst mistake I’ve ever made,” he says. “Sometimes you’d be up for, like, five days. And after three days you start seeing these shadows.”

The fall was quick. Rodriguez went from living in an apartment to living under bridges. From using occasionally to using habitually. Meth morphed into heroin—and heroin, for Tony, is the devil. “It f---s up everything,” he says. “I want to find the other side of life again. I want to be the person I should be. But it’s so damn hard.”

On the morning of Nov. 2, under a black Las Vegas sky, the air crisp and cool, Rodriguez and a friend named Johnny Ellis departed early from the rented garage that both men (and a handful of other recently homeless people) use for lodging. They were driving south on Rainbow Boulevard in Tony’s rusted, unregistered white GMC truck, en route to gather metal, when they encountered two demolished cars. One was aflame.

Rodriguez says he parked his truck in the middle of the street, got out and heard a woman screaming. Kilgo-Washington was standing outside of Ruggs’s Corvette, pleading for help. As Rodriguez sprinted toward her, he says he saw a young-looking Black man in a black sweatshirt, his lower body still planted inside the car but his torso dangling on the road. “I was about to tell her not to move him, but it was too late—she grabbed him and pulled him fully out,” Rodriguez says. “I have no idea who he is. I don’t care about football. Never heard of Henry Ruggs. But I didn’t see no life in his body. I thought he was dead.”

Rodriguez and Ellis ran next for Tintor’s RAV4, which by then was engulfed in flames. All four windows were closed and the doors were locked. Ellis dashed back to the truck and returned with a hammer. He smashed in the passenger-side window, and when he found no one inside he flipped the tool to Rodriguez, who was kneeling by the driver.

Rodriguez hammered open the driver’s window, reached in and gripped an arm. “Johnny!” he screamed, finding Tintor and her dog. “They’re here! They’re here!”

By now, smoke was oozing out of the SUV’s front windows; it was nearly impossible to see or breathe near the car. Still, Rodriguez punctured a discharged airbag with the hammer and yelled “Come on!” to Tintor inside. “You have to help me! You have to!” He could hear breathing, but a seatbelt was wrapped tight around the driver’s body. He yanked, tugged, pulled—to no avail. “I was trying to cut it out, trying to figure out a way,” he says. “Nothing was working. I started on the door, fighting to open it. To get this person out somehow.”

Ethan Miller/Getty Images

A security guard from a nearby residential complex tried to assist, then bailed when the smoke became too thick. Rodriguez remembers that someone else showed up with a small fire extinguisher, but with the car coated in flames it was useless. “One more guy came and tried to help, then jumped away,” Rodriguez remembers. “Then Johnny jumped away. And it was really me by myself. I don’t know why God put me in that position. I couldn’t do anything.”

The heat became insufferable. Rodriguez knew it was time to leave. But something kept him there. Dropping out of school. Picking up dead bodies. Living on heroin and meth. Stealing scrap metal. He is the father to four children, none of whom he raised. Life has been one screw-up after another. He hated himself. Hated what he’d done.

But here was another human, needing him. Needing Tony Rodriguez’s hands.

It felt like hours—the smoke and the heat, waiting for the emergency workers to arrive. In reality, it all lasted no more than 10 minutes. But now hope was gone. The car was barely visible. Rodriguez didn’t know who was inside, only that they had to be dead.

“Tony!” Ellis yelled out. “There’s nothing we can do!”

As the two friends retreated to the truck, Rodriguez (whose recollections are backed by police reports and witness retellings) remembers staring down at his palms, coated with Tina Tintor’s blood. He opened his truck door, turned the key and drove up Rainbow Boulevard, “the orange of fire filling the rearview mirror,” he says. “You could hear the tires popping from the heat.”

A mile or so down the road, Rodriguez says he pulled into the parking lot of Spring Valley Hospital. “Johnny,” he said, “I have to get this blood off of me. And I have to pray.”

They entered the building and found a sink. Rodriguez can still picture the water turning red as it pooled in the drain. He can still hear his prayers echoing off the tile. Rodriguez is not a religious man. He cannot remember the last time he entered a church. But it all came out.

“Please, God, get me through this. Please, God…”

Back in Starbucks, Rodriguez is holding the warm cup in a cold room that he can’t feel.

“I’m gonna be honest,” he says. “God hasn’t gotten me through it.”

Tina Tintor was buried as she lived. Quietly. Humbly. Her resting place in the rear of Palm Memorial Park is easy to miss. No stone has yet been placed, merely a white wooden cross with TINA TINTOR running horizontally in black and gold decals, bisecting the years of her birth (1998) and death (2021). A small ornament with Max’s picture on it dangles from a red ribbon. Miles away, outside her home, a small piece of paper with a picture of Tina, protected from the elements by plastic, reads: Under the tremendous pain and saddens [sic] we announce passing of our beloved.

When police finally arrived on the scene of that passing, Tintor’s car was a ball of fire, and Ruggs and his girlfriend were sitting on the sidewalk in a state of shocked disbelief. The Raiders’ receiver refused a field sobriety test, but later, at a hospital, blood was drawn and his BAC was found to be 0.16%. According to the police report, Ruggs was placed in trauma bed No.1, where investigators tried unsuccessfully to conduct an interview.

Less than 24 hours after the accident, the Raiders issued a one-sentence statement, cutting the receiver. That afternoon he was released from the hospital and booked at the Clark County Detention Center, where he was charged with reckless driving and DUI resulting in death. (He was also hit with misdemeanor gun possession after police reported finding a loaded handgun in his wrecked vehicle.) Ruggs was released the next day on $150,000 bail.

Steve Marcus/Pool/Getty Images

When, in the shadow of the accident, Raiders quarterback Derek Carr addressed the media about his teammate, he spoke of a broken heart. “He needs people to love him right now,” Carr said of Ruggs. “He’s probably feeling a certain way about himself right now. And he needs to be loved.”

As you read this, Ruggs is a fly trapped in amber—a prisoner in a decadent home that once symbolized all of his success. He remains on house arrest pending a preliminary hearing on May 19. If he is found guilty on all charges, he faces upwards of 50 years in prison.

“We’re human,” says Mac Hereford, who lined up at receiver alongside Ruggs at Alabama. “And people make horrible mistakes.”

“This whole thing has f---ed me up.”

Tony Rodriguez is still here, in Starbucks, but he’s not entirely here. His eyes are glassy. He’s staring off into the distance. He assures me he has not yet taken his daily heroin hit today. “Later,” he says.

I watch him, curious what’s running through the mind of a man who has seen too much. Then he snaps out of it.

“This whole experience, it’s done something to me,” he says. “I’ve withdrawn from my girlfriend, from my friends. I thought I was going to be able to live with this. But … I dunno. It’s something I need to deal with.”

To Rodriguez, this pain can feel misplaced. He lived. Tina Tintor died. “I’m not the victim,” he says. “That poor woman is.” The garage that he calls home is near the accident site, and he passes it seven, eight, maybe 10 times per day. He set up a small vigil nearby with some flowers and candles, and one recent morning he woke beside it. “I fell asleep there,” he says, “just thinking about it all.”

Some of the candles disappeared recently. The flowers are dead. Rodriquez still visits. “I have to,” he says.

On the darkest of days, Rodriguez replays the entire tragedy. Did he do enough? Could he have saved Tintor? There was another tool in his truck, alongside the hammer—a pipe bar, used for digging. “I bet I could have jammed open the door with it,” he says. “Why didn’t I?” Sitting in a coffee shop, he can still see the flames and feel the heat. He hears the tires popping. His hand is touching Tina Tintor’s arm. He is back there. Always back there.

Courtesy of Jeff Pearlman

“People have told me I’m a hero,” he says. “I’m not a hero. I’m not even close to a hero. A hero saves that woman. I didn’t.”

A pause.

“To be honest, I kind of wish I’d crashed instead of her,” he says. “She had her whole life ahead of her. Everything waiting for her.

“What do I have?”

There is nothing to say. The cup of coffee is nearly empty. Tony Rodriguez is nearly empty, too. I ask if I can buy him another drink, and he tells me Brittany loves caramel. I purchase a large iced beverage, pass it toward him.

“Thanks, man,” he says. “It’s kind of you.”

We shake hands and rise to leave. Rodriguez’s truck—“too many miles to count”—sits in the parking lot, a sore thumb amidst all the Vegas vanity. Tony will deliver the drink to his girlfriend. Then they will shoot their heroin.

“You asked me about the drugs,” Rodriguez says before opening the door to his truck. “You asked me why I do ’em. Heroin, it makes me forget about things. About all the things I’ve seen.”

He pauses.

“The problem,” he says about what he witnessed four months ago on Rainbow Boulevard, “is it’s always there. No matter what I do, it always comes back.”

Read more of SI’s Daily Cover stories here:

• Their Countries Are on Opposite Sides of a War, but They Stand United

• Inside Tito Ortiz’s Tumultuous Term Governing His Hometown

• ‘I Am Lia’: The Trans Swimmer Dividing America Tells Her Story_