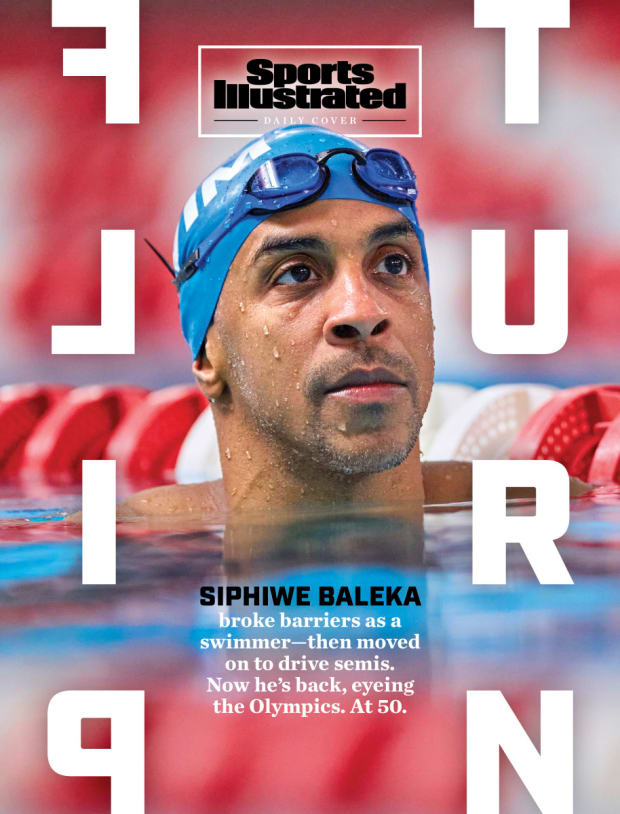

Siphiwe Baleka broke Ivy League barriers as a swimmer—then dropped the sport to drive semis. Now he's back in the pool.

It’s a snapshot that’s being replicated all over the world. Athletes at the height of their physical powers, training for the next Olympics. By turns, they are imbued with both a sense of anticipation and a sense of uncertainty. The goal is to stay conditioned and sharp, without peaking too soon.

Again and again they’ve been assured that the Tokyo Games, delayed for 2020, will be staged next summer. But they’ve also been warned that these Games will be like no other, and, as the cliché goes, to “expect the unexpected.” Likely, there will be no fans in the stands. Maybe there will be no athletes’ village. Maybe the format for the competition will be altered.

In these ways, Siphiwe Baleka is like nearly all his fellow Olympic aspirants. A swimmer, he usually arrives for training early, 4:45 a.m. on this day; other times he arrives late at night. But each time he jumps into the pool and begins an hour’s worth of laps, his arms and legs working in synchronicity, his motion at once economical and extravagant. He is trying to stay in shape and bend time, shaving down his personal best. He is also cautious of rationing his energies, saving what he calls “my best self” for when he enters the pool in Tokyo the last week in July, 2021.

The comparisons, though, between this Olympic hopeful and thousands of others worldwide, effectively end there. For one, he represents the country of Guinea-Bissau, a West African republic with a population of less than two million, its Olympic profile so modest that it has never sent a delegation of more than five athletes to the Games and has never won a medal of any kind. Without the benefit of a federation to help fund his training, he has to work full-time, which, until recently, the former All–Ivy League swimmer did by driving an 18-wheeler.

And there’s this: the guy knocking off all those early morning laps in the pool? This upcoming April, months before the Opening Ceremony in Tokyo, he will turn 50 years old.

***

A native of Oswego, Ill., in the early 90s, Tony Blake—as he was known then—sliced through water faster than all but a small handful of college swimmers. At 5’ 8” and 148 pounds, Blake was a sprinter but he would also train in distance lanes. At Yale, he would swim the 50-, 100- and 200-meter freestyle, the 100- and 200-meter breaststroke and—a bit of symbolism for the fiercely singular competitor—the 200-meter individual medley.

As a sophomore, Blake finished fifth in the Eastern Seaboard Championship and became the first Black swimmer to be named First Team All–Ivy League. Then, as a junior, he entered the 1991 U.S. Open Swimming Championships with hopes of qualifying for the 1992 U.S. Olympic team that would compete at the Barcelona Games.

Like most competitive swimmers, Blake had harbored Olympic ambitions for most of his life. He funneled his training into the 100-meter freestyle event. His times were off, but not by much. If everything broke right, who knew? “It was my last, best shot of ever qualifying for the Olympics,” he says. "I got myself to a point where I felt good about my chances.”

But when the day came, he swam a poor race. In the 100-meter freestyle, Blake says, he missed qualifying by .8 seconds. It wasn’t just that he had failed; it’s that, up to that point, his life had been a constellation of successes and falling short had barely occurred to him. A consoling friend said he could always try again for the Atlanta Games in 1996. But Blake knew that he’d be 25 by then, practically geriatric, he reckoned, in the dog years of swimming. Right there in that Minneapolis cool-down pool, he tearfully administered last rites to his dream. “I was heartbroken," he says. "This was the first time I wanted to do something and couldn't do it.”

Blake returned to campus, but had lost his buoyancy. After a roommate found him passed out near bottles of pills, he was sent to the psychiatric ward of Yale–New Haven Hospital. Blake says it wasn't an earnest suicide attempt—"It was more of an academic exercise," he says—but he wasn't allowed to check out until a few days later, when his coach came and vouched that Blake wasn't a danger to himself.

Blake kept swimming, and swimming well. As a senior, he led the winning relay team when Yale beat Harvard and Princeton to win a share of the Ivy League swim title. Then, a few weeks after that—and a few weeks short of graduation—Blake dropped out of school. He had been reading about towering figures in history. He figured it was time to go searching for truth away from campus. "All of this is garbage if you don't actually do it,” he says. “Yale wasn't helping me; it was stifling me. I know people thought I was nuts for leaving when I did, but I didn't want to be there."

In 2014, Sports Illustrated caught up with Blake. But he was no longer Blake. In the 20-plus years since he’d been a college athlete, he had traveled the world, including stops in Ghana, Benin, Togo, South Africa and Ethiopia, using money he had saved, he says, making wood furniture and doing desktop publishing. In South Africa he met with tribal elders. They said that when a son of the soil returns home, a new name is conferred on him. They dubbed him Siphiwe (pronounced seh-PEE-way), a name common among the Xhosa and Zulu tribes. They said it means Gift of the Creator. For a surname, they chose Baleka, an anagram of “A. Blake” that variously (and appropriately) means “fast” and “he who had escaped.”

Though Siphiwe Baleka had returned to Yale to pick off those last few credits, graduating in 1996, he ended up finding a line of work that required no college degree. In 2008, he became a long-haul trucker. From his base in Springfield, Mo.—the headquarters for Prime Inc., one of the country’s largest commercial fleets—Baleka climbed into his steel whale and drove around the country. One week he’d be delivering steaks to Seattle; the following week, it could be appliances to Miami.

Soon, driving was only the half of it. A former elite athlete, he was appalled by what trucking could do the human body. Because of the rigors of the road, truckers have some of the highest obesity and morbidity rates of any profession. “The world’s unhealthiest profession,” Baleka called it. And he couldn’t abide by this. He would pull into truck stops to exercise, often using his cab for resistance.

He would run sprints around his rig. In the rare instances he wasn’t feeling time pressure, he would go for rides mid-route on a fold-up bike he kept in the cab. For every driver who flashed him a funny look, 10 would ask for tips. Soon Baleka, effectively the Jane Fonda of the long-haul set, was leading exercise classes and designing fitness regimens specific to drivers. (Full disclosure: He and I collaborated on a book, “Four Minute Fit.”)

Baleka is nothing if not a searcher. And around the same time, he spat into a tube and sent his DNA to African Ancestry, which specializes in the genealogy of people of color. The results came back after a few weeks: on his paternal side, Baleka descended 100% from the Balanta, an ethnic tribe from West Africa. While the Balanta span several countries, in Guinea-Bissau they represent the largest ethnic group and roughly one-quarter of the population.

“I started looking for information on the Balanta just as a curiosity,” he says. “There wasn’t much there because they never had leaders or kings. Western scholarship was never interested in them. I started compiling and writing anything I could. This is heritage. Eventually, I founded the Balanta History and Genealogy Society.”

When he wasn’t maneuvering an 18-wheeler across ribbons of interstate, when he wasn’t helping his colleagues get in shape, and when he wasn’t going down what he calls “the rabbit hole of my history,” Baleka was back in the pool. He realized that swimming, not unlike bike-riding, is a skill that cannot be unlearned. The strokes and rhythms felt instantly familiar in the water, his natural habitat. Shedding body fat and time in equal measure, he came within a few pounds of his college weight and a few seconds of his college times.

In the meaty years of his 40s, he began swimming in masters events, and his competitive fire flickered at first and then burned steadily. He began winning events, turning in times comparable to the best masters swimmers, including Rowdy Gaines. “I wanted to be the best in the world,” he says. “It was like, I wanted it in my 20s and I want it again now.”

In 2017, Baleka entered the World Masters Championship in Budapest, ranked first in two events. He ended up winning four silver medals, but no golds. He wasn’t the best in the world. He got a little of the same sting he felt at the U.S. Olympic trials more than a quarter-century before. But it wasn’t as intense. It helped that he proposed to his girlfriend on the medal stand. He also emerged with a new goal: swimming in the next Summer Olympics.

Like many of Baleka’s ideas, it sounded, at first, crazy. Until it didn’t. In the course of studying his ancestry, Baleka came to learn a great deal about Guinea-Bissau. It’s the fifteenth-poorest country in the world, with an average per capita income at around $800. (For comparison: in the United States, it’s around $65,000.) According to the United Nations’ Human Development Index, it ranks among the least developed countries in the world.

The United States has no embassy in Guinea-Bissau. So Baleka has reached out directly to government leaders and tribal elders. Baleka tells the story of a conversation he had with Balanta elders. He had asked a simple question: “What do you need most urgently?” The response surprised him. The elders said: “We need solar panels for this pump and we need taps.” When Baleka asked why, they explained that people have to pull water from a well and carry it home.

He also learned that there were only a handful of swimming pools in the entire country. “I’m thinking,” says Baleka, “that if I became a citizen, I would probably be the best swimmer in the entire country.”

Then he thought of Eric Moussambani. Remember Eric the Eel? He had taken up swimming after high school in Equatorial Guinea, a small country in central Africa. At the Sydney Olympics, he represented his country in the 100-meter freestyle. When two competitors in his heat false-started, he had the pool to himself. It was the longest distance he had ever swum, as his native country had no Olympic-sized facility. Mid-race, he began struggling. The crowd sensed this and cheered him on. His time was irrelevant; he finished the race. It marked one of the great heartstring moments in Olympic history, fodder for a classic NBC “spirit-of-the-Games” vignette.

With some digging, Baleka realized that the same program that enabled Moussambani to compete in Sydney was still in effect. Under the International Olympic Committee’s “universality system,” spots are reserved for smaller countries with developing programs in select sports. Not only does universality exist for swimming, but the standards have been eased for the Tokyo Games, on account of the pandemic.

Suddenly galvanized by the not-unrealistic goal of becoming an Olympic swimmer, Baleka stopped driving his truck and cut back on his trucker fitness programs and trained with a single-minded pursuit. Last October, he competed in the first International Masters Swimming Championship in Cairo. He won six gold medals. He swam with his body painted in traditional African designs. He took the medal stand draped in the Guinea Bissau flag with the word “Balanta” written across it.

He did some quick math in Cairo. His time of 24.96 seconds in the 50-meter freestyle was less than a second off his best time as a college swimmer. He is not in the same time zone as, say, Brazil’s César Cielo, who holds the world record in the 50 free at 20.91. Then again, had Baleka competed in the Rio Games, he would have swum faster than 27 competitors. Says Baleka: “I’m realistic—which is not something I say often. I’m not winning an Olympic medal. I’m not coming in first. But I’m not coming in last either.”

In January, Baleka visited Guinea Bissau, the first member of his family to return since they were forced to leave during the Middle Passage 250 years and 10 generations ago. He was already a minor celebrity in his motherland, the image of him wearing the Balanta shirt in Cairo having rocketed around the country. He was assured that gaining citizenship would not be a problem.

The Ledger Hotel in the capital city of Bissau is home to one of the nation’s few pools, and the manager made a barter deal with Baleka: If he gave swimming lessons to the locals, he could not only use the pool for training, but also stay in a room free of charge.

Baleka returned home to southwestern Missouri fired up with more confidence than ever, only for COVID-19 to hit. In some senses, it’s been a curse. He is unemployed, no longer working for Prime, and his finances have been battered. He’s also struggled to find pool time. (He usually trains in the pool at Drury University on Springfield’s north side but the only available slot is 4:45 to 5:45 a.m.) Then again, the pandemic has also allowed him an extra year of training and extra time to make his appeal to swimming authorities.

As it stands now, Baleka needs the funds—and COVID-19 travel clearances—to return to Guinea Bissau so the country can grant him citizenship and so that its National Olympic Committee can formally submit a “universality places” application on his behalf. Baleka and Guinea Bissau must then appeal to Dr. Mohamed Diop of Senegal, the FINA Bureau Member and president of the Senegalese Swimming Federation, who is highly influential in the approval process for the universality swimming slots.

Diop has thus far responded tepidly to Baleka’s unusual quest and request, informing the Guinea Bissau Olympic Committee that Baleka needed to “prove” himself by competing in a series of races in South Africa. “This is nearly impossible on such short notice, and quite impossible when the lockdown began,” says Baleka. He also responded that, by competing in Cairo, he had already proven himself at an international swimming event held on the African continent. Diop, he says, did not get back to him. (Diop did not return SI’s messages seeking comment.)

As Baleka has studied the history of his ancestral home he’s realized that the notion that Guinea Bissau has no swimming history isn’t really accurate. “When Europeans first came to West Africa, it was the West Africans who were the best swimmers. A sign of the effects of the last 500 years is how Europeans went from being the worst swimmers to the best and Africans went from being the best to the worst, including a drownings crisis among African American and African European swimmers,” he says. “[Imagine] what this would mean to the people of Guinea Bissau, especially if this could lead to a national swim program.”

Then there’s the full circle—the flip-turn, as it were—aspect of Baleka’s personal swimming journey. When he was in his early 20s and failed to make the Olympic team, he did not think his ambitions were simply being deferred for 28 years. “When you dream about making it to the Olympics, you don’t imagine yourself there at the age of 50,” he says. “But, trust me, life takes you to different and exciting places, and sends you in directions you never expected.”