Over the first few days of competition, the sport has put the world on display: how it’s changing, becoming more inclusive, less traditional and more diverse.

Sign up for our free daily Olympics newsletter: Very Olympic Today. You'll catch up on the top stories, smaller events, things you may have missed while you were sleeping and links to the best writing from SI’s reporters on the ground in Tokyo.

TOKYO — The rain resumed shortly after 8:30 p.m. here Monday, ramping up in stages, from drizzle to downpour to deluge. There were hurdles on the track at National Stadium. Runners, too, along with umbrellas, ponchos and those little white robot cars that measure throws. By then, an important point had become clear: those cars are not only precise and festive; they’re also waterproof.

“For those of you disappointed not to get tickets to the swimming venue, you’ve discovered it,” boomed the announcer over the loudspeakers playing in a mostly empty venue. He was, of course, laughing, unspooling a dad joke from dry ground. The athletes who spent their entire lives waiting for this exact moment, only to be super-soaked, did not crack so much as a smile. For some reason, "Sweet Caroline" began playing at max volume.

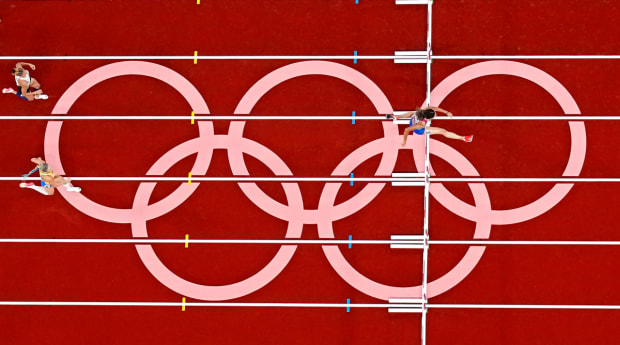

There stood Sydney McLaughlin, the 400-meter hurdles specialist and reigning world record holder. The American favorite bounced in the starting blocks, her steel gaze pointed forward, rain falling in biblical sheets. An opponent promptly jumped the gun, leading to a disqualification and another distraction. No matter. No matter the downpour and no matter the stakes, McLaughlin shot around the track as if running above the clouds, the event she has long dominated. By the time she had circled toward the finish line, she led by the length of a semi-truck, beating her closest competitor by 1.19 seconds in a race that concludes in under a minute.

Her performance, while expected, continued a theme at track and field for this Olympics, the first held in 17 years without a certain sprinter from Jamaica of worldwide renown. No, Usain Bolt was not here, nor were his primary competitors, titans like Justin Gatlin, Asafa Powell and Tyson Gay. But that didn’t matter, either. Not when track and field took a Games defined by a pandemic, low television ratings and a distinct lack of electricity and reminded those who were watching what makes the Olympics, well, the Olympics.

Sunday night featured two medal ceremonies, back-to-back national anthems for Italy that served to further illuminate the first four days of track and field competition here. There was Lamont Marcell Jacobs, a 26-year-old speedster born in El Paso who competed for Italy, who won the 100-meter dash and became the so-called fastest man in the world, surprising even … himself. The journalists from his country formed the best “crowd” at these Olympics, with wide eyes and standing ovations and chants of Italia! It felt right to have a crowd again.

As Jacobs stood atop the medal podium, his eyes welled with tears. He thumped his chest. And then he found Gianmarco Tamberi, a fellow Italian competitor, both men wrapped together in their country’s flag as they embraced.

Tamberi also climbed atop the medal podium. But he did not climb alone. Mutaz Essa Barshim of Qatar stood next to him, thanks to an Olympic quirk. All night Sunday, Tamberi and Barshim dueled in style, with Barshim sporting sunglasses that all but covered his face and Tamberi leaning into the theatrics, waving his arms before attempts to summon whatever noise he could, then celebrating with fist pumps and flexed muscles and little dances, his face the definition of either anguish or delight.

When both men failed three times to clear 2.39 meters (or roughly 7 feet, 10 inches), they were called over by the event judges and presented with an option neither knew existed: they could partake in a jump-off, which just sounds cool, like a high jump decided by penalty kicks; or they could stop right there and win golds. As in, both of them, which sounded far cooler to anyone other than those who prefer 50% odds over 100% ones. So cool, in fact, that Barshim shattered those shades of his while celebrating.

This was how track unspooled over the last few days, like a giant pinball machine of elite athletes attaining remarkable feats, the focus shifting from the oval to the jump pits to the infield. Those in attendance forgot about COVID-19 momentarily, as competitors unfurled their own bolts of energy to an empty stadium, shifting the focus from who was not here to who was and breathing life into these pandemic Games.

Three female Jamaican sprinters swept the 100 meters; one, Elaine Thompson-Herah broke a 33-year-old Olympic record by one one-hundredth of a second, defending her gold from Rio.

An American shot-putter, Raven Saunders, dyed her hair green and purple, wore a plastic filter mask and Air Jordans, and won silver on Sunday. At the ceremony, she stepped down and crossed her arms above her head after receiving it, drawing an X and attention, she said, to “the intersection of where all people who are oppressed meet.”

On Sunday, sprinter Fred Kerley won the silver in the 100 meters. This, after what he called the best sleep of his night, a full 13 hours. More proof that mental health matters. And so does youth. With his medal hanging around neck, he walked off the track in slow motion. It was like he wanted to take the moment in, which is how it felt to sit here, transfixed by drama inside this stadium—and the Italian reporters.

Yulimar Rojas of Venezuela also competed Sunday, the stadium stopping every time she began a triple jump attempt. An LGBTQ advocate with hair dyed pink, she did not disappoint, adding a world record to her gold-medal-winning attempt of 15.67 meters (about 51 feet, 5 inches). This was the world on display, how it’s changing, becoming more inclusive, less traditional, more diverse. That's a good thing.

Mr. Jumps, or JuVaughn Harrison, became the first Olympian since Jim Thorpe more than 100 years ago to compete in both the long and high jumps at one Games. Mr. Jumps acquitted himself well, finishing seventh and fifth, respectively, while cementing that moniker with four days of leaps.

On Monday, the pace continued unabated. Jasmine Camacho-Quinn nabbed a gold in the women’s 100-meter hurdles. She became the first athlete from Puerto Rico to medal in these Olympics and won the first track and field gold in the history of her country and just the second overall.

American Keni Harrison won that silver. Later Monday night, her countrywoman, Valarie Allman, triumphed in the discus, ran to the stands, hugged her coach and draped an American flag over her shoulders. Now, she can get back to Stanford, Olympic excitement injection complete.

So it went, and so it will go. Heads must remain on swivels to keep up. After qualifying on Monday, Thompson-Herah, Shelly-Ann Frazier-Pryce of Jamaica and America’s new sprint star Gabby Thomas will square off in the 200-meter final. Another American contender, sprinter Noah Lyles, will begin his 200 heats; the prodigious Armand Duplantis, a pole vaulter who lives in Louisiana but competes for Sweden, will seek to continue his unmatched dominance; seven-time long jump world champion Brittney Reese—nickname B-Reese Da Beast—will try and add one final medal in her final Olympics.

McLaughlin will be back, too, for the 400-meter hurdles final. Rain or shine, expect speed, theatrics and a reminder of one sport that delivers, always. The one with lowered expectations for Tokyo that has already exceeded them.

More Olympics Coverage:

• Former Gymnasts Left Paralyzed Are No Stranger to the Struggles Biles Faced

• Bright Future Ahead for U.S. Swimming After Tokyo

• It's Time to Appreciate the Olympic Legacy of Brittney Reese

• Caeleb Dressel's Picture-Perfect Tokyo Olympics