After his Pan Am Games protest made waves, U.S. Olympic fencer Race Imboden continues to push for athlete rights, racial and social justice.

NEW YORK — On a Sunday morning in September, Race Imboden mixed into the crowd in front of City Hall. The 700 or so in attendance would soon embark on a protest run on the six-month anniversary of the death of Breonna Taylor, the 26-year-old Black woman who Louisville police officers killed in her apartment during a botched raid.

Imboden stood and listened as five Black women spoke to protesters and shared their encounters with racism and law enforcement. Taxis and cars hummed by, but the crowd stayed silent. Their time to make noise came moments later when the protesters moved onto the Brooklyn Bridge and alternated shouting Taylor’s name and calls to charge the officers who fired the shots.

Before walking toward the bridge, Imboden turned and said, “We need more of this.” Protesting is nothing new for him.

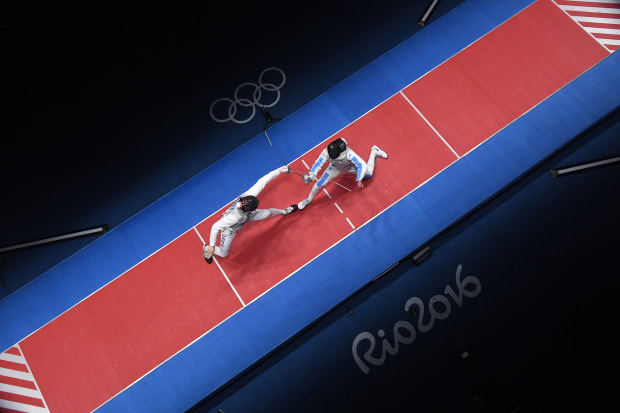

Imboden is a U.S. Olympian with a bronze medal from the 2016 Games in Rio de Janeiro. He has been fencing since he was nine years old, and he turned professional in 2013, when he dropped out of St. John’s University. Since then, he's been a regular in international fencing competitions and owns five World Cup competition gold medals. After winning a gold medal in the men’s team foil at last summer’s Pan American Games in Lima, Peru, Imboden was aiming to compete at the Tokyo Olympics. But the COVID-19 pandemic postponed those plans until at least next year and has left him working out in New York City parks while the fencing community figures out how to return to normalcy.

Despite his success on the piste, it was Imboden’s decision to take a knee on the medal podium in Peru while the Star-Spangled Banner played that drew mainstream attention.

He explained his decision to protest in a series of tweets saying: “We must call for change. This week I am honored to represent Team USA at the Pan Am Games, taking home Gold and Bronze. My pride however has been cut short by the multiple shortcomings of the country I hold so dear to my heart. Racism, Gun Control, mistreatment of immigrants, and a president who spreads hate are at the top of a long list. I chose to sacrifie [sic] my moment today at the top of the podium to call attention to issues that I believe need to be addressed. I encourage others to please use your platforms for empowerment and change.”

This wasn’t the first time Imboden had taken a knee on the podium. He did it at the Pharaoh's Challenge men’s foil fencing World Cup in October 2017 with teammate Miles Chamley-Watson, but it garnered little publicity. Imboden says his decision to protest three years ago was his way of showing support for other athletes being punished for taking the same stance, particularly in the NFL.

“I realized that I needed to speak to people who looked like me,” says Imboden, who is white. “When I took a knee, I directed it at people who looked like me. I knew that it would make them uncomfortable to see a kid like me kneeling.”

Imboden and Chamley-Watson were not disciplined for their demonstration. But that wasn’t the case in 2019.

On the same day of Imboden’s protest in Lima, U.S. hammer thrower Gwen Berry raised her fist toward the end of the national anthem after winning her event. U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee CEO Sarah Hirshland sent Berry and Imboden letters saying they were being placed on a 12-month probation for their demonstration. It was the governing body’s way of sending a message that any athletes hoping to break the IOC’s rules against political protests in Tokyo would be reprimanded.

“My letter to the USOC in response to my probation asked to set up places for athletes to speak outside of medal stand protests. It was ignored,” Imboden says. “I have been partaking in this conversation for a very long time. Do I think I had a full understanding of the effects as deeply I do now? Absolutely not. I don’t think any of us did.”

Sports Illustrated spoke with Berry in early June about her reaction to the uprising and awakening in the U.S., she said: “When I took my stance, I was completely misunderstood. Now I feel like everyone feels how I felt.” Although she put together one of the best seasons of her career and finished ranked as the No. 3 hammer thrower in the world, Berry lost sponsors and a majority of her annual income. But she has absolutely no regrets about taking her stand. When the USOPC issued a letter to U.S. athletes condemning “systemic inequality that disproportionately impacts Black Americans in the United States,” Berry was quick to point out the hypocrisy and demanded an apology from them.

The USOPC organized a town hall where athletes could openly discuss how they had been personally impacted by racism in America and recent protests. Imboden was invited as a facilitator, but declined. While Berry garnered more media attention in recent months, Imboden reached out to her to show his support but primarily stayed out of the limelight.

“Because there are so many voices and because so many people started to speak up, the trend was to yell louder and be the loudest,” Imboden says. “I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to find out how I could use my voice in a way that drives change. That’s very difficult to do. My voice is the same as it’s always been.”

Imboden did accept a spot as a member of the steering committee for protests and demonstrations on a 44-person Team USA Council on Racial and Social Justice that was assembled by the USOPC and national governing bodies in August. John Carlos, who raised his fist in protest with teammate Tommie Smith at the 1968 Olympics, is also on his team.

Carlos and Imboden have been vocal about abolishing Rule 50 of the Olympic charter, which says: “No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.” In June, the IOC stressed that athletes will face bans for hand gestures, kneeling or any political messages or armbands displayed. The IOC said athletes could freely express themselves in interviews, press conferences and social media throughout the Games. Imboden has also seen the number of athletes participating in these discussions diminish since their first meeting. It is why when asked if he also finally feels “understood” like Berry, he says he feels the opposite.

“What does us talking about this do? We communicate this to someone, who then goes into a room with someone who we don’t know, to vote? How much power do we hold? How much do these conversations matter?” he says. “The excuse has always been that this takes time. We’ve heard it forever. We’re experiencing a lot. I’m just not sure that the excuses are enough anymore.”

For an Olympic athlete in an individual sport, it can be more challenging to take a stand. Finances might not be as stable as that of an NFL player; it’s rare to get millions of viewers on a game like NBA players. Imboden has an Olympic medal tucked away in his New York City apartment, but still models and works outside of his sport to make a living and a name for himself. When LeBron James considered walking away from what ended up being a championship-winning season for his Lakers, Imboden was moved. Next summer, he views the ultimate sacrifice as U.S. athletes’ walking away from the Olympic Games in a protest. While he’s not promoting that idea, he says there are athletes discussing it.

There are critics who might question Imboden’s sincerity, or point out the dissonance of a white athlete assuming a leadership position in the national fight for racial justice. But to him and so many of his peers, the movement for athlete rights is inextricably tied to the push for racial and social justice.

“Some people don’t believe me, and they don’t think it’s genuine,” Imboden says. “All of that stuff I had to prove. I believe that I have.”

Athletes like Imboden and Berry have fought for the right to use their platform as stars in their sport to voice concerns over enormous social issues, and don’t intend to stop anytime soon. The stakes are high, and the road ahead long, but Imboden intends to continue applying pressure wherever he can to the powers that be, for the ability to live freely and with dignity.

“I’ve been consistent with my efforts and I knew that I had to be reflective and open. I knew I had to listen and then turn around and be human by pushing myself and elevating myself so that my message can reach as many people as possible,” he says. “I do think I’m fighting for the right thing.”