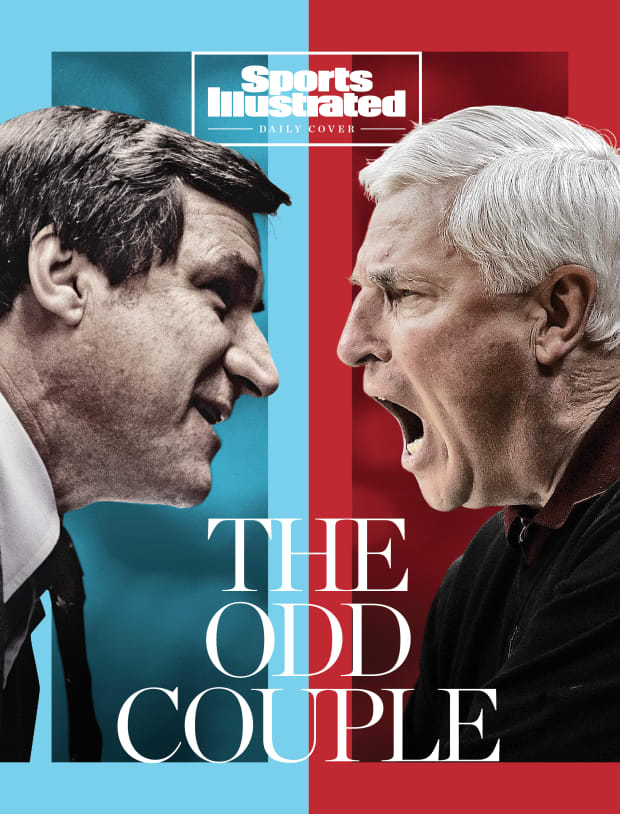

On the surface, they couldn’t have been more different. Yet Dean Smith and Bob Knight forged one of the most enduring—and most unlikely—friendships in college sports.

Dean Smith was fuming. This North Carolina team he was coaching was supposed to be better than this. Playing in Los Angeles at the Bruin Classic, the Tar Heels gave up open shot after open shot and lost to Minnesota, 76–60. ACC play was opening in barely a week, and this was not an auspicious sign.

Bob Knight was fuming. This Indiana team he was coaching was supposed to be better than this. Playing in Honolulu at the Rainbow Classic, the Hoosiers gave up open shot after open shot and lost to Texas-Pan American, 66–60. Big Ten play was opening in barely a week, and this was not an auspicious sign.

After the defeat North Carolina took a commercial flight home from L.A., changing planes in Kansas City. On that same night, Dec. 30, 1980, Indiana, fresh off one of the worst losses in program history, flew home from Hawai‘i and changed planes in . . . Kansas City. And wouldn’t you know it, the Tar Heels and the Hoosiers—who had played each other in Chapel Hill 10 days earlier, a 65–56 UNC win—were just a few departure gates away from each other.

Rich Clarkson/NCAA Photos/Getty Images (Smith); Streeter Lecka/Getty Images (Knight)

It was late and the players, equally exhausted and dejected, didn’t mingle much. But the coaches greeted each other, two friends shaking their heads at the serendipity. Meeting like this? In the freakin’ Kansas City airport? What are the odds?

Smith had remarried—as Knight would a few years later—and had recently become a father with his second wife. Now he had to get his daughter to sleep. He invited Knight to accompany him as he strolled the baby through the concourses.

So with all the airport shops closed, as dozens of abnormally tall young men slumped over seats, two of the sport’s most accomplished coaches took a walk and griped about their teams. Does Minnesota always shoot that well? From that deep?

Knight wondered aloud about how he could get two players at the same position—power forwards Ray Tolbert and Landon Turner—to operate effectively together. On it went, two coaches strategizing and commiserating until the boarding announcements.

Knight and Smith would meet again, three months later. Their teams, considerably improved, faced off in the 1981 NCAA final. The Hoosiers won 63–50, but any disappointment in Chapel Hill was short-lived. A preposterously talented player named Michael Jordan would soon arrive on campus, and in 1982, North Carolina would succeed Indiana as national champs. After which Knight confided to a friend, “If we weren’t going to win again, I’m happy it was Dean.”

Dean and Bob. Bob and Dean. Two of the sharpest basketball cortexes, rivals who between them would win five national titles and nearly 1,800 games. For decades, during the season and in the offseason, Knight and Smith would call each other—sometimes to talk basketball, sometimes to talk life. They would visit each other. They would play golf together. And often, they would swap long, handwritten letters.

Together they formed one of college basketball’s deepest—and most unlikely—friendships.

On March 22, 1984, Michael Jordan played his final college game. He was held to just 13 points as his top-seeded Tar Heels fell to the fourth-seeded Hoosiers, 72–68, in the Sweet 16. Jordan, though, had hardly seen the last of Knight. A few weeks later he packed a duffel bag for Indiana to audition for the 1984 U.S. Olympic team, which Knight was coaching.

That summer night, Knight had presciently declared MJ the best basketball player he had ever seen. Asked in Bloomington for the biggest difference between his college and Olympic coaches, Jordan smiled. “Coach Smith is the master of the four-corner offense,” he said, pausing a beat. “Coach Knight is the master of the four-letter word.”

Jordan could have kept the bit going. Smith was almost a decade older, Knight six inches taller. Their temperaments, leadership styles and ideas of decorum were jarringly at odds. And Lord knows, they were at different coordinates politically.

For all that, they were fast friends.

Their bond had many sources, starting with their middle-class upbringings in Middle America towns. The son of a railroad man and a teacher, Knight was from Orrville, Ohio. Smith grew up mostly in Emporia, Kans., where both his parents taught and his father also coached basketball. Knight was 24 when he became the coach at Army. Before taking the UNC job, at 30, Smith spent a season as an assistant at Air Force. Each played on a championship team, Smith at Kansas in 1952 and Knight at Ohio State in ’60. Both led programs at flagship universities in states rich with basketball tradition and could relate to the pressures and privileges that came with the role.

They also held a common—or at least vastly overlapping—set of basketball principles. Running a clean program. Stressing process over outcome. Seeing to it that their players went to class. Believing firmly in defense, film study and the idea that a team ought to be greater than the sum of its parts.

Knight rejected out of hand the notion of having names on the back of IU’s red-and-white jerseys. Smith famously instructed his players that, upon scoring a basket, they ought to point to the teammate who passed them the ball. Old joke: Who was the only man to hold Michael Jordan to under 20 points a game? Dean Smith.

“The mutual characteristics were actually very strong,” says Eddie Fogler, a longtime Tar Heels assistant who saw the friendship firsthand. “You had two great coaches who had this love for the game, this respect for the game, and love and respect and care for the athletes.”

Owing in no small part to Smith and Knight’s fondness, Indiana and UNC scheduled a home-and-home series. The night before the games, the two coaches would dine together. They would not only bring their respective staffs, but Knight also regularly included his close friend Bob Hammel, a longtime sportswriter for the Bloomington Herald-Times. “Coaches and their staffs sitting down to dinner before a big game—and inviting the local media?” says Fogler. “Yeah, that doesn’t happen today, does it?”

Consider this: In the spring of 1980, Knight called Smith seeking his opinion. His protégé, Mike Krzyzewski—who played for Knight at Army, served as an Indiana assistant and then, like Knight, took his first head job at West Point—was in the running for two openings the following season: Iowa State and Duke. Knight reckoned that because Iowa State was in the Big Eight, a lesser conference than the ACC, there would be less pressure to win. Smith didn’t disagree but thought Krzyzewski would have an easier time recruiting in Durham than in Ames. That was enough for Knight, who threw his full force behind getting Duke to hire Krzyzewski. Which it did.

Here’s another throwback: Roy Williams recalls that when he was a Carolina assistant in the 1980s, he began to get restless. Around the same time, Knight was trying to add someone to his staff. As Williams remembers it: “Coach Smith said to Coach Knight, ‘Well, who are you looking for?’ ”

“And I think Coach Knight said, ‘Somebody like Roy.’ ”

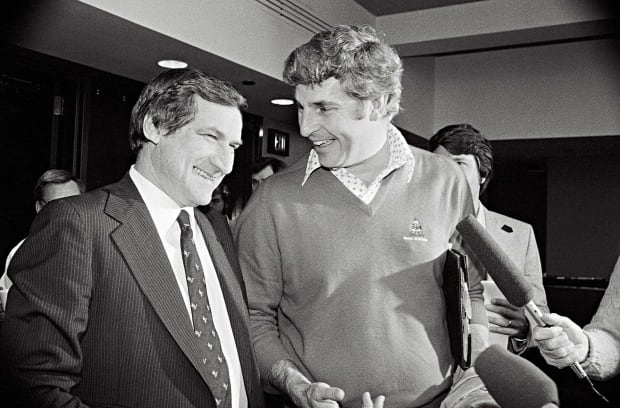

Bettmann/Getty Images

Smith offered to lend Williams to Knight for a year. Knight would get access to a bright, diligent coach. Williams would get exposure to another program and would likely return energized and with new ideas. Smith was, apparently, unconcerned that Knight would try to poach Williams. Knight was, apparently, unconcerned that Williams would return with trade secrets.

Williams went home to bounce the idea off his wife, Wanda. She had just read John Feinstein’s A Season on the Brink, which portrayed Knight as both a basketball genius and an emotionally turbulent bully. “She said, ‘Are you serious?’ ” Williams recalls. He graciously declined the sabbatical: “When I told Coach Knight that story, he thought that was the funniest thing he’d ever heard. But, yeah, that shows you what great friends they were and what trust they had.”

Hammel remembers this moment from the 1981 Final Four: In the first game, Indiana trailed LSU at halftime 30–27. While walking to the pressroom, through the bowels of The Spectrum in Philadelphia, Hammel passed Dean Smith.

Aware that Carolina was to play Virginia in the second game, and believing Smith was focused on his preparations, Hammel decided to pass in silence. But Smith, without breaking stride, muttered to Hammel, “We’ve got to get [Indiana forward] Tolbert playing better this half.”

Hammel was surprised that Smith had been paying such close attention to the Hoosiers’ game. But what really stopped Hammel cold? Smith’s use of the pronoun we.

There doesn’t seem to be an obvious Dean and Bob origin story. Friends surmise that they first met at a coaching clinic or convention in the early 1970s. The consensus is that their connection deepened in ’76. (Smith died in 2015; Knight’s health did not allow for a conversation today.)

That year Indiana won the NCAA title and went unbeaten, a feat that hasn’t been accomplished since. That same year, Smith was the coach of the U.S. Olympic team. After the squad’s debacle at the 1972 Munich Games—the U.S. lost the gold medal game to the Soviets, owing largely to scandalous timekeeping—Smith needed to reestablish his nation’s basketball supremacy.

Smith took a “team of rivals” approach: College coaches who competed fiercely would now come together to help select the team. Knight was among those Smith invited to tryouts in Raleigh.

Southern Historical Collection, The Louis Round Wilson Special Collection Library/University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

In the end Smith chose four members of his own team: Phil Ford, Mitch Kupchak, Walter Davis and Tom LaGarde. But two of the starters were Hoosiers, Quinn Buckner and Scott May. “I liked the idea of having Knight’s players, who were disciplined and well-grounded in fundamentals,” Smith wrote in his 1999 memoir, A Coach’s Life. “The work habits of the North Carolina and Indiana players set the tone for the whole team.” The U.S., which, in the end, did not have to go through the Soviets, won gold.

Eight years later, Knight served as Olympic coach. He, too, was expected to win gold and also reestablish supremacy after the 1980 boycott. Emulating Smith, he invited rival coaches to Bloomington, often watching the trials from an elevated platform, Smith by his side. Two starters on Knight’s ’84 team were Tar Heels—Jordan and Sam Perkins—and the U.S. won gold.

Dean Smith was three years old when his father coached an Emporia High team that not only won the 1934 state Class A title but was also the first racially integrated basketball entry in Kansas tournament history. Yet when Smith was a senior at Topeka High, the school had two teams, one for white players and one for Black players. Smith protested vigorously. The year after he graduated, the teams of Topeka High integrated.

Smith was only warming up. When he arrived in Chapel Hill as an assistant coach in 1958, one of his first acts was to accompany a Black student into a local restaurant with a whites-only policy. As head coach, defying a state stuck in the Jim Crow era, Smith recruited the first Black scholarship athlete to UNC, guard Charlie Scott. When he wasn’t protesting the Vietnam War, Smith was opposing capital punishment or recording radio spots advocating a freeze on nuclear weapons. In 2013, President Obama honored Smith with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor, saying, “His successes go far beyond X’s and O’s.”

Knight skewed considerably to the right of Smith. He was a firm believer in the supremacy of the U.S., and if a conflict required military might, so be it. He believed he paid too much in taxes. He was never accused of being a feminist or a social progressive.

Knight and Smith, though, didn’t ignore their differences. They debated and tried to explain to each other the error in his thinking. Says Williams: “[Smith] would always say that we had the same end in what we were trying to do.” (Mutual friends do think their relationship would have been challenged by Knight’s support of Donald Trump.)

Like any friends, they had their laughs and their inside jokes. In the fall of 1988 Indiana and North Carolina played in the Preseason NIT at Madison Square Garden. Ahead of the tournament, the coaches, team officials and media were invited to a promotional cocktail party at the World Trade Center. It was the kind of schmoozefest that Knight hated and, accordingly, he declined.

Southern Historical Collection, The Louis Round Wilson Special Collection Library/University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

But Smith, with Williams and Fogler, headed to downtown Manhattan. Hammel recalls that, over hors d’oeuvres and between cigarette breaks, Smith worked the room. Eventually, he made his way over to the man who was—titularly, anyway—Knight’s boss: Ralph Floyd, Indiana’s athletic director. Floyd was there with his wife, Sue. She and Dean soon realized that they, improbably, shared a hometown and had even attended the same church in Emporia.

When Smith told Floyd his father’s name, she paused, and then stared delightedly at Smith.

“Oh, wait!” she said. “You’re little Deanie!”

Smith was crowding 60 at the time.

As Hammel recalls it, Smith blushed, while behind him, Williams and Fogler practically chewed their sleeves to avoid howling with laughter. Soon enough, the “Little Deanie” story made its way to Knight, who filed it away for future deployment.

The Smith-Knight bonhomie extended to former assistants such as Williams, too. In 1988, he moved on to coach Kansas. Before a game against Indiana, his wife, Wanda, baked brownies for Knight and his team. The two coaches met again years later, when Williams was at North Carolina and Knight at Texas Tech. Williams remembers that, before the game, Knight emerged from the locker room stone-faced. “Where’s Wanda?” he demanded as the coaches met at midcourt. Nervously, Williams pointed to the stands, where his wife smiled warmly and waved. Knight then strode sternly over to her and, in a voice loud enough for all to hear demanded, “Where are my f------ brownies?”

Like most friendships, the one between Smith and Knight benefited from common enemies, or at least figures that neither held in high esteem. That Final Four game in which Smith referred to Indiana as we? It was, perhaps, no coincidence that the opponent was LSU, whose coach, Dale Brown, was not always reputed to confer full faith and credit on the NCAA rule book.

More seriously, friends say that Smith and Knight were united in their disdain for Kentucky’s segregationist coach Adolph Rupp and thought him unworthy of being considered one of the titans of the profession. In 1997, Smith challenged Rupp for all-time coaching victories among Division I men’s coaches. Knight watched raptly. “When Coach Smith won that [877th] game, there was no one happier than Coach Knight,” says Hammel. (On Dec. 23, 2006, Knight, then at Texas Tech, tied Smith’s mark.)

For years in Bloomington, Knight wielded power and influence that rivaled that of the governor. Local prospects knew that if they didn’t want to play for Indiana, there was a way they could stay in the good graces of Knight—and by extension Hoosier Nation. They could sign with UNC. So it was that Indiana became a mini pipeline to Chapel Hill, where Eric Montross, Rick Fox and Tyler Zeller all became stars.

This remained true even when Knight’s time with the Hoosiers reached its stormy conclusion. In 2000, after a former player said that Knight had choked him in practice, other allegations of violent and bullying behavior started to spill out. Following an investigation, Indiana gave Knight one more chance, but by September he was gone.

The next year, Scott May’s son Sean was a senior at Bloomington High North and ranked among the best players in the country, a power forward with an NBA-ready body. Had Sean stayed in town and played for Indiana, it would have been seen in some quarters as an act of betrayal, playing for the school that had run off Knight. Leaving Bloomington had its complications, too. May minimized them by choosing UNC. “No question,” says Ford, who became a Smith assistant. “[We] got a look at Sean because of Scott’s and [Indiana’s] relationship with the Carolina program.” May would help lead the Tar Heels to the 2005 national championship.

Rich Clarkson/NCAA Photos/Getty Images

’84 Olympics.

Peter Read Miller/Sports Illustrated

One way Smith reciprocated: He often came to Knight’s defense. When Knight was first nominated for the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1987, a member of the selection panel tried to block the nomination because of the coach’s notoriety. Hearing of this, Knight being Knight told the Hall to shove it and to perform other acts of impurity on itself.

Someone at the Hall responded that the institution could exist quite nicely without Bob Knight. Before Knight could return fire, Smith stepped in, playing peacemaker but siding with his friend. Knight was inducted in 1991.

In 1997, this magazine ran a long story, headlined KNIGHT ERRANT, which opened: “After several years of feeble finishes and now a public squabble between coach and player, even Indiana basketball fans are asking, has Bob Knight lost it?” In response, a letter to the editor arrived bearing a Chapel Hill postmark, which SI would print in full:

Coach Knight was and is a brilliant technical coach and teacher of skills. He is a great recruiter. Sophomore Jason Collier and incoming freshman Luke Recker could have gone to any school in the country, but they chose Indiana because of Knight. Knight will not cheat in recruiting, although many coaches in the Hall of Fame with him have been on NCAA probation. Knight demands that his athletes get their degrees. Every school would like to have a coach who wins games, whose players have been recruited legally and who graduate, and who brings in millions of dollars to support the many men’s and women’s programs that cannot support themselves. I am not aware of any player who has graduated from Indiana who is not grateful to Coach Knight for his experience with the Indiana basketball program. —Dean Smith, Chapel Hill, N.C.

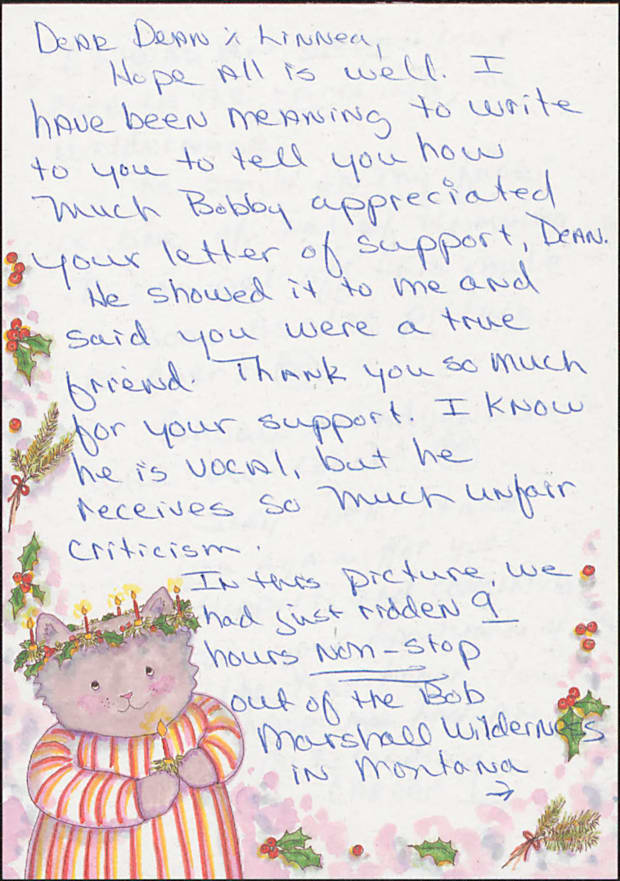

Knight would later write to Smith: I gave the copy of your letter to Karen [Knight’s wife] that you wrote to Sports Illustrated. Before she read it, I told her no one had ever done or said anything on my behalf that I appreciated as much. . . . As she read the letter tears trickled down her cheeks and when she finished reading she looked at me with tears on her face and said, “Dean Smith is a real friend.”

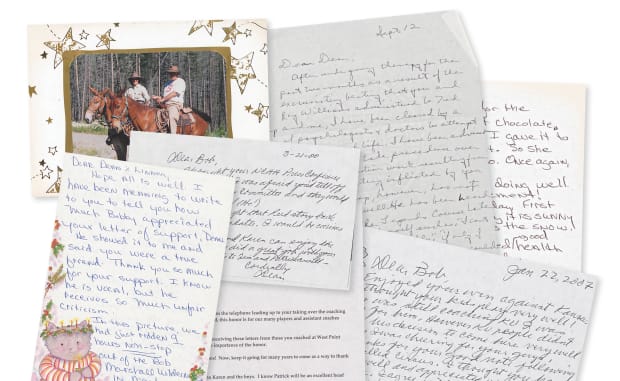

We know this because Smith donated his letters and writings to the UNC library. Amid photos dating back to Kansas, documents pertaining to Jordan, audio from talks—a man ahead of his time, he often gave the keynote for campus-wide flu shot and vaccine kickoffs—Smith included his correspondences with Knight. There are three folders holding more than 200 digitized items.

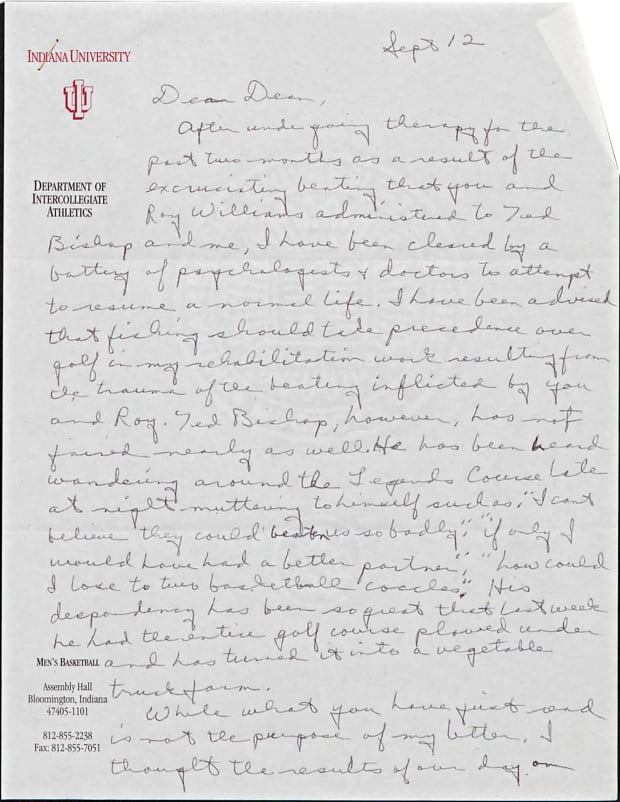

The Smith-Knight letters range from the serious to the mundane (“A late thank you for the organic coffee, tea and hot chocolate”) to the personal. They are filled with inside jokes and golf yuks. Knight once wrote: After undergoing therapy for the past two months as a result of the excruciating beating you and Roy Williams administered to Ted Bishop and me, I have been cleansed by a battery of psychoanalysts and doctors to attempt to resume a normal life. . . . Ted Bishop, however, has not fared nearly as well. He has been heard wandering around the Legends Course muttering to himself . . . how could I lose to two basketball coaches?

Southern Historical Collection, The Louis Round Wilson Special Collection Library/University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Amid Knight’s ugly denouement at Indiana, in April 2000, he wrote to Smith “to get your thoughts about what I should do.” Before calling him back, Smith scrawled notes, so, one imagines, he would be best prepared to offer counsel:

Bob, for what it’s worth—certainly you are in the position to make good decisions.

1) Stay where you are. 2) You say you will try to change to more standard centralized techniques. Actually the players over the years laughed about them when they have graduated. 3) Remind them Indiana has won more (70s-80s-90s) than other Big Ten—graduated at a high rate.

The collection of letters between Knight and Smith stops in the early 2000s. Smith retired in 1997 and within a few years was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and dementia. Suddenly, he was seldom seen in public. Cared for by a heroic spouse, here was a fiercely proud leader of men who, by his 80s, was deeply dependent.

One of his core strengths had always been his memory; now Smith struggled to recall names and faces. Until the end, friends wondered whether he could still access the memories—the Final Fours; the Olympic gold; Jordan, No. 23, hitting that jumper from the left baseline in the Superdome in 1982; all those branches on his coaching tree. He died seven years ago at 83.

By that time, Knight had long retired. And while he was working for ESPN at the time, his memory and health may well have already been failing, too. Today, at 81, Knight has returned to Bloomington. Cared for by a heroic spouse, here was a fiercely proud leader of men who, in his 80s, is deeply dependent.

One of his core strengths was always his memory; now Knight struggles to recall names and faces. Friends wonder whether he could still access the memories—the Final Fours; the Olympic gold; Keith Smart, No. 23, hitting that jumper from the left baseline in the Superdome in 1987; all those branches on his coaching tree.

One last bit of symmetry between these two coaching titans and dear friends: Look at the winningest Division I coaches. At the top of the list, you’ll see Krzyzewski, now in his final season at Duke, a onetime acolyte of Knight and longtime rival of Smith. Scan down and you’ll see Knight with 902 wins, sixth all-time. Smith is next with 879.

Others may come along and surpass their marks. But here they are, side by side, not unlike those two sleep-deprived coaches traipsing through the Kansas City airport all those years ago. You have to figure that if history recalls Smith and Knight like this—back-to-back, bracketed together—it would be just fine by them.

More Daily Covers: