Twenty years after the greatest U.S. men’s run in the modern era, the team with arguably the greatest potential takes to the World Cup stage.

Back in Frisco, Texas, the U.S. men’s national team’s unexpected and thrilling run to the 2002 World Cup quarterfinals is commemorated permanently at the National Soccer Hall of Fame by a player’s participation medal and a No. 17 DaMarcus Beasley jersey signed by members of that historic squad.

But those two pieces of memorabilia don’t begin to convey the depth of that tournament’s long-term significance. For a more complete, immersive, flesh-and-blood exhibit, head about 8,000 miles east to Qatar. Here, the resonance of that U.S. run, and the transformative impact it had on the men who engineered it (and, consequently, those who followed), will be on full display.

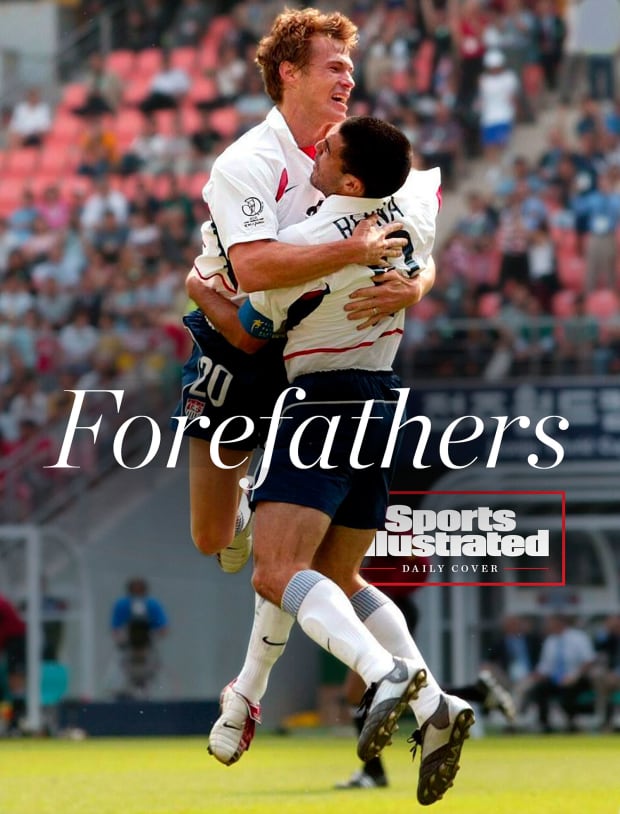

This month, and then in December if things go well, that 2002 team—regarded as the greatest in American men’s soccer’s modest history—will stage a mini 20-year reunion at the ’22 World Cup. The pair that dazzled in South Korea as 20-year-olds and offered a dose of welcome fearlessness to that veteran ’02 side will be here. Landon Donovan, now the coach of the USL Championship’s San Diego Loyal, will be working as a broadcaster. Beasley, a co-owner and director at USL League Two team Fort Wayne FC, is coming to Qatar as well. He’ll be acting as an MLS ambassador while doing some TV for Fox, as will Hall of Famer Cobi Jones. The captain of the ’02 team, Claudio Reyna, will be in the stands watching his son Gio, the gifted 20-year-old attacker who’s finally healthy and poised to add to his family’s legacy (mom Danielle was a U.S. international as well).

PanoramiC/Imago Images

Then there’s the trio who bookended that five-game 2002 journey with surprising moments that remain lodged in American soccer lore. The current U.S. squad, which was the youngest on the planet through much of qualifying, will kick off the World Cup against Wales on Monday as the second-youngest in the competition (35-year-old defender Tim Ream tipped the scales). And it’s been built meticulously over the past three-plus years by three ’02 alumni.

U.S. Soccer sporting director Earnie Stewart, men’s GM Brian McBride and coach Gregg Berhalter don’t share many stories of their Korean exploits with their players. But that World Cup helped inform their team-building philosophies, and it served as a springboard to their post-playing careers. A good World Cup can elevate and then cement personal relationships that bear professional fruit years later. It provides a valuable blueprint for future projects, while adding a veneer of achievement and gravitas to any résumé.

“I don’t think it's a coincidence,” Stewart says of the 2002 team’s fingerprints on this new U.S. side and American soccer at large.

“Now to say that we were sitting around a dinner table [in 2002] and Jeff [Agoos] and I are talking ‘Oh, you're gonna be doing that?’ That was also not the case,” Stewart adds. “The thing that I see there is kind of the passion for the sport. So when we sat around tables, it wasn't about all kinds of other things. It was about the game. It was about training. … That group influencing each other to have those conversations and then later on, when you do get there and you see people in different roles, you think ‘Hey, that actually makes a lot of sense.’”

Stewart, McBride and Berhalter arrived in Korea during a moment of uncertainty for American soccer. The 1998 World Cup had been a disaster for the U.S., a fractured team that lost all three matches and finished dead last in the 32-nation tournament. And MLS was teetering, having contracted clubs in Miami and Tampa before the 2002 season. There was just one soccer-specific stadium at that time (in Columbus), and only four investors sharing ownership of all 10 MLS teams.

The sport needed a boost, and it came just four minutes into the World Cup opener against highly touted and heavily favored Portugal in Suwon, South Korea. Stewart, wearing the captain’s armband while Reyna nursed a muscle injury, whipped in a corner kick that McBride, the fearless center forward, got his head to in the penalty area. Portugal goalkeeper Vítor Baía made the diving save but couldn’t control the rebound, and U.S. midfielder John O’Brien finished from close range. There was shock and euphoria, and, by the time it wore off, after an own goal and a score from McBride, the Americans were up by three.

Imago Images

The nail-biting 3–2 win over the fifth-ranked Portuguese sparked the U.S. on a run that would briefly capture the national imagination, take it through the famous round-of-16 win over Mexico and then into the quarterfinals against powerhouse (and eventual 2002 runner-up) Germany. There, in Ulsan, the Americans played perhaps their best game of the tournament before falling, 1–0, in controversial circumstances. Early in the second half, Berhalter’s lunging first-time shot was blocked on the goal line by the arm of German defender Torsten Frings. But Scottish referee Hugh Dallas wasn’t interested in intervening.

The U.S. had enjoyed some good fortune that summer—it advanced to the second round only because South Korea scored a late goal against Portugal in their group-stage finale. The Americans then drew a second-round opponent they knew they could beat. But the luck ran dry in Ulsan. World Cups are fickle, and the margins are razor thin.

“I had the feeling that the referee didn't want us to go to the next round,” Berhalter said in a U.S. Soccer retrospective. “I just had the feeling that he knows the place of football in the world, and he couldn't bear to see Germany getting knocked out by the United States.”

America’s status did rise a bit from there, however.

"I remember going back to the Premier League [with Sunderland], and my profile changed just from your colleagues’ level of respect,” Claudio Reyna told U.S. Soccer.

World Cups can validate you, especially in a country where soccer becomes truly mainstream only once every four years. They open doors and change narratives. McBride went on to become a Premier League fixture at Fulham, where he remains an icon. Stewart entered management and worked as a technical or sporting director at two Dutch clubs before moving on to the Philadelphia Union and then U.S. Soccer in the summer of 2018. At that point, he became the first “soccer person” with administrative control over the national team. And Berhalter went into coaching, first as an assistant under ’02 U.S. manager Bruce Arena at the LA Galaxy, then to the head jobs at Sweden’s Hammarby IF and the Columbus Crew.

Imago Images (2)

The three men were bonded and seasoned by their experience in South Korea, and Stewart leaned on that when deciding who he’d entrust with reshaping the U.S. men.

“Gregg is a very curious individual,” Stewart says. “He's always had that but after his [playing] career, when he was at Hammarby and I was at AZ Alkmaar, he’d call sometimes just to hear things and ask, ‘How do you guys organize that?’”

“He’s a very curious person into how to better himself—back in the day as a player then later on as a coach—and he's always had that. Brian is somebody who is about relationships, and he’s really, really good at that piece, and that just comes natural to him. He had that within the [U.S.] playing squad and he still possesses those qualities.”

McBride was part of the 1998 debacle and the 2002 triumph (as well as the ’06 World Cup team), and believes a blueprint can be fashioned from both highs and lows.

“Just like we talk about giving our younger players more experiences at higher levels, it helps you. It helps you understand how games are shaped, how teams are built, the good teams and teams that fail,” McBride explains. “All those things and understanding those experiences and having gone through them, it helps you. There’s no doubt about it. And then knowing people, understanding people and being able to communicate to individuals. So you make sure that connection is also there.”

Interestingly, that communication doesn’t happen through stories and tales of games and goals gone by. The 26 players representing the U.S. here in Qatar all know to some extent what their managers and forebears achieved. But it wasn’t a lived experience for most. Only 11 of the 26 were at least 5 years old during the 2002 World Cup, and three weren’t even born.

“I was in my mom's belly at the time. That’s what my mom tells me,” Gio Reyna says.

U.S. Soccer | Brad Smith/ISI Photos/Getty Images

For them, these are stories that, if not portrayed in black and white, are at most standard def. They were also authored by a group of men who seem more interested in using their experience than crowing about it.

“They’ve been very few and far between where there’s ever been any conversations. … It’s not about us anymore,” McBride says. “There’s times when you can interject possibilities from experiences, but to get into detail is only necessary unless there’s an issue or some fear. Curiosity is great, and you can quickly go over it. But it never gets into detail with things that are going to take their focus away from what they need to do on the field, because everybody’s experience eventually is going to be different individually.”

Berhalter adds, “I think we’re very selective about when we talk about ourselves. I think if we can impart wisdom on the guys, we do that. But it’s more about looking forward.”

Individuals might approach him and ask about something like playing at the cavernous Estadio Azteca in Mexico City, Berhalter says. But it hasn’t been collective, and there’s been no sense that players have any interest in immersing themselves in U.S. national team history.

“What does it help to tell them that we won a game at a World Cup? I don’t necessarily see that. If we’re asked about experiences or ‘How would you do this? Or how would you do that?’ We definitely try to help. But to show some kind of highlight reel of 20 years ago—this is a different game,” Stewart says.

So has he been asked about his experiences, or about how he would do this or that?

“No!”

“They’re in their careers. They’re busy,” he continues. “I don't know if I did that with Tab [Ramos], as an example, who was in the 1990 World Cup. I didn't do that in ’94—ask him about his experiences. And that's even closer [in time]. I was so concerned and worried about my own career.”

Multiple current U.S. players have said that 2002 rarely, if ever, comes up.

“No, not at all. I’ve never talked to any one of them about that,” forward Tim Weah says. “We know the greatness. Hopefully that switches over to us.”

Defender Joe Scally, who grew up in New York as a friend and teammate of Gio Reyna, says that Claudio “never really did” tell stories about 2002. Even Gio admits that his father “doesn’t really like to talk about himself.”

Courtesy of U.S. Soccer

The current squad’s only World Cup veteran, DeAndre Yedlin, was 8 in the summer of 2002.

“It's interesting,” the defender says. “I would like to hear about that, to be honest. But I think at the end of the day, it’s just focused on this group, and that’s what they’re really trying to do.”

Yedlin is astute. That’s exactly what’s going on. Stewart, McBride and Berhalter are harnessing their World Cup experience in a different way—not by sharing it verbally or via grainy highlights, but by using it to guide the construction of a group they think will have the collective strength to compensate for youth and deficits in quality.

“If we want to be successful at the World Cup, we’re not going to have the most talent in the World Cup. So we have to gain an advantage in other areas. And our advantage is our brotherhood,” Berhalter says.

Both he and Stewart were on the bench at times in Korea. Berhalter, a defender, didn’t play a minute during the group stage, then took the field as Arena switched formations and helped the U.S. shut down Mexico and then, nearly, Germany. The lack of overt ego within that 2002 squad, and the absence of players putting their own ambitions above the team’s, created an advantage, the trio says. You can’t account for bounces or fate during a World Cup. It’s not up to you whether Korea scores against Portugal or whether that handball by Germany is called. Culture and locker room composition, however, is.

Imago Images

“When you talk about teams, it's not only putting the best players together. It’s actually putting players together that can actually function as a team. Bruce did an amazing job of that in 2002 in putting this group together that was there through thick and thin even though sometimes a player did not play and probably was disappointed,” recalls Stewart, who was a knockout-round substitute.

“In the end, everybody got their head straight that they knew it was about that team at that moment,” he adds. “If I thought about ’98, I felt that was kind of like the [problem]. Everybody was pissed off at a certain moment within that tournament, and it hurt the team dynamic. That was something that Bruce managed really, really well in 2002, even while he also had to disappoint people.”

Berhalter has taken that lesson and run with it, spending significant amounts of time, resources, energy and study on constructing a cultural foundation for a squad that was built basically from scratch following the program’s failure to qualify four years ago. From the empathetic manner and increased frequency with which coaches communicate with players, to the way they structure meetings, meals, field trips and training sessions, to the perks available in the hotels and players’ lounge, just about everything is geared meticulously toward fostering that brotherhood.

“The attention to detail from Gregg is something that you recognize and that will always stay with you. He had that as a player and he has that now as a coach,” Stewart says.

"What the guys don’t realize is that what we're doing is based on what we've learned from the World Cup and what we learned from the national team,” Berhalter explains. “In 2002, we had a really close team. And that’s why we were very intentional about how we wanted to create this environment with this group. So even though we're not saying explicitly, ‘Listen guys, in 2002 the group was really close, and when we’re really close we're going to be good.’ We've used the last three and a half years to build what we think is the key to success.”

The players who’ve made it to Qatar are true believers. Multiple people around U.S. Soccer have said that this group is the most comparable to 2002 in terms of interpersonal chemistry and support. That word, “brotherhood,” is heard repeatedly from players and staff alike. The pursuit of it is one ripple effect of that run in Korea 20 years ago.

“First, it’s about building a culture, which we’ve done over the past four years. And the staff and Gregg have done a great job of that and kind of saying, ‘These are our values. This is what we stand for,’” says Yedlin, who’s played under four U.S. managers.

Among those values, he says, are “being hardworking” and “making people feel welcome.” Another is, “whatever’s best for the team.”

Yedlin explains, “I know there’s going to be times when I don’t play. But it’s, ‘What can I do to have the guy in my position and everybody else on the field be at their best?’ The better the team does, the better I do.

“The feeling you get when you’re with this group is literally that everyone genuinely wants the best for you.”

There’s a funny moment during a Canal+ podcast recorded this summer by U.S. midfielder Weston McKennie and his Juventus teammate Polish goalkeeper Wojciech Szczęsny. McKennie mentioned that he remembered watching the U.S. play Poland in a 2006 friendly while growing up in Germany. Szczęsny and his Polish cohost then reminded McKennie that Poland met the U.S. in the group-stage finale of the ’02 World Cup.

“Who won?” McKennie asked.

When told the final score (3–1 Poland, with the U.S. still advancing thanks to that goal from South Korea). McKennie deadpanned, “Lucky game, maybe. Probably lucky.”

He was 3 years old when that match took place. The box score isn’t relevant. But that tournament is, in large part because it was a significant catalyst for the environment McKennie’s in now. Arena was a players’ coach, someone who recognized the importance of chemistry and empathy, and of providing space and support for individuals to express themselves. Berhalter is similar, even in difficult moments. Berhalter sent McKennie home from the opening World Cup qualifying camp in September 2021 because the midfielder violated the team’s coronavirus protocols. It was done in a firm and fatherly way, however. McKennie’s place in the group and his affection for the staff remained secure.

"I’ve had many situations where I can—any player can, really—just go to someone on the coaching staff and sit down and have a life talk with them,” McKennie says. “I think that’s beneficial for us outside of soccer, in general. We’re human beings. We have a life outside of soccer.”

Ashley Landis/AP

A life outside of soccer, sure. But it’s worth considering how many of the 23 men who went to Korea two decades ago also have a life in soccer. It was, as Stewart said, a group that loved the game, and being associated with a run like the one they experienced in 2002 can only help. Just two of Arena’s 23 work outside the industry. Berhalter, Donovan, newly minted MLS Cup champ Steve Cherundolo, Pablo Mastroeni, Josh Wolff and Carlos Llamosa are coaching. Wolff works for sporting director Claudio Reyna at Austin FC. Eddie Pope was an agent and now is launching a new MLS Next Pro team in his native North Carolina. Agoos is a senior VP at MLS. Eddie Lewis runs a company that furnishes training programs and O’Brien is a sports psychologist. Goalkeepers Kasey Keller and Tony Meola do TV.

“If you've experienced a World Cup, positively or negatively, I think people do take that into account,” Stewart says. “We’re all lucky to be part of it, and that our names are somewhat attached to it. We all understand how big this tournament is. It’s the biggest sport and tournament in the world and it’s on the global stage. But it’s not going to help us to remind the players that every single day. It’s just not.”

So they keep the details to themselves and focus on trying to re-create the magic. It’s tough to guess how this new, young U.S. team will fare here. Its four-nation, first-round group, which also includes England and Iran, is the toughest at this World Cup based on average FIFA ranking. No. 19 Wales isn’t as prohibitive an opening-game favorite as Portugal was 20 years ago, but it’s a team full of Premier League players that’s proved tough to break down. A three-goal, first-half explosion would be great. But that stunning salvo in South Korea will be hard to replicate.

The next two weeks are an unknown. Berhalter has said that the only thing you can count on going into an event like a World Cup is that it’s not going to go how you think it is. So when the 2002 alumni do give advice, it’s focused on something under the players’ control. It’s about soaking it in, so if one day they’re called upon to make use of what they learned or experienced, it’s there.

“I’m 100% sure that Gregg and I … have emphasized to enjoy the competition and the challenge that’s in front of you. And that is something from day one that has always been part of it. No matter who we play you have to enjoy it at the same time,” Stewart says.

That’s what Gio Reyna has taken away from captain Claudio as well.

“He told me [it’s] a moment not to take for granted and yeah, just enjoy it. It’s a special moment,” the younger Reyna says. “World Cups don’t come around too often, so you gotta enjoy the moment.”