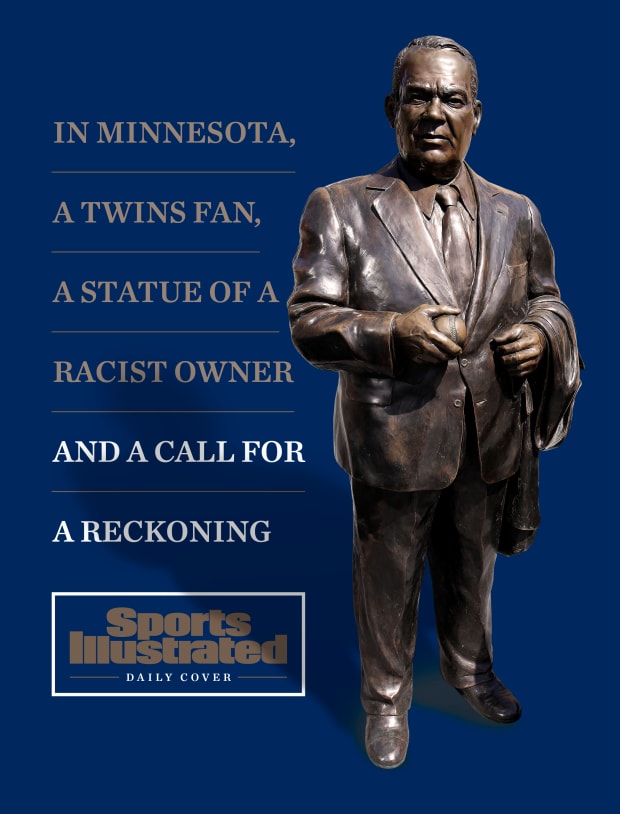

In Minneapolis, not far from where George Floyd was killed by a police officer, furor has been festering over the still-standing statue of a racist former Twins owner. This morning, it came down.

Last week, a pair of news items pushed Mike Tucker to a breaking point with his favorite baseball team.

First, the 44-year-old lifelong Twins fan watched a video of Native American–led activists at the Minnesota state capitol hurling a rope around a Christopher Columbus monument, hauling the genocidal colonizer to the ground. A day later, he read about how the Carolina Panthers had removed a monument to the team’s former owner, Jerry Richardson—former because of the accounts of racial and sexual misconduct that led to his selling the franchise in 2018—from outside their stadium, albeit with a mechanical crane (and for “public safety” reasons, the team said) rather than with raw human might.

Following along at his Minneapolis apartment, a straight two-mile shot up Chicago Avenue from the intersection where a fellow Black man named George Floyd was killed by a white police officer on May 25, Tucker was galvanized by a familiar fight. “The climate of what’s happening, it just felt like enough was enough,” Tucker says. “These two things were a sign that somebody was talking to me.”

Since 2015, Tucker says, he has quietly staged a “one-man boycott” of his beloved Twins, protesting a statue of former team owner Calvin Griffith that stands in front of Target Field. For someone who describes himself as a “ride-or-die” Twins loyalist, this has been no small sacrifice. Worn-out team gear still speckles his closet—his favorite item: a Carlos Gomez jersey with the G, O and Z scratched off on the back, so it reads just ME—but Tucker hasn’t bought anything new in five years. And, whereas he once attended as many games each season as his schedule and wallet would allow, including the famous Game 163 winner-take-all playoff against the Tigers in ’09, he now refuses to so much as set foot on the stadium’s downtown grounds. “I don’t want to see that statue,” he says, “until it’s lying on its back, or taken down by the Twins.”

Aside from rattling off the late Griffith’s well-documented résumé of racism and bigotry to anyone who’d listen, though, Tucker had never found the time to plan a real grassroots campaign for the statue’s removal. Then Floyd’s death sparked an overdue reckoning of this country’s racist roots, forcing a nationwide reconsideration of the monuments to Confederate leaders, slaveholders and other problematic historical figures that still stand in public spaces.

And so it was that Tucker logged onto Facebook, created a new group—MN Twins fans for removal of calvin griffith statue at Target Field—and invited everyone on his friends list, hoping to rally a few allies. Support, though, arrived much faster than Tucker anticipated. The group surpassed 250 members on Thursday, while more than 230 had signed a Change.org petition directed at current team owner James Pohlad, whose family bought the franchise from Griffith in 1984, calling for the statue to be torn down. Maybe this doesn’t seem like a lot of people. “But if you consider that I’ve been protesting by myself for four-plus years,” Tucker says, “I feel like the whole world’s behind me.”

It might as well be. Consider recent efforts across the sports world alone. A petition to rename the University of Cincinnati’s baseball stadium, which bears the moniker of known anti-Semite Marge Schott, has just shy of 10,000 signatures and the endorsement of Bearcats alum Kevin Youkilis. Heisman Trophy winner Johnny Manziel and current Texas A&M quarterback Kellen Mond are among tens of thousands more who want to bring down a campus statue of former school president Lawrence Sullivan Ross, a brigadier general in the Confederate army. A couple hours away, University of Texas athletes have refused to participate in recruitment or donor events unless, among other demands, a campus statue of segregationist James Hogg is removed. And Memphis Grizzlies rookie Ja Morant recently sent a passionate letter to a county judge in Kentucky, urging the same fate for a Robert E. Lee statue and a monument to Confederate soldiers in Murray, where Morant played in college.

“We can't change the culture of racism unless we change the celebration of racism,” Morant wrote. “Please help us take a stand and remove the symbol of hatred and oppression.”

No statue is just a hunk of stone or metal. If a person stands there, frozen in time, then so cast is what that person stood for. As Tucker sees things: Why should Twins fans continue tolerating a reminder of the last MLB owner to house players in racially segregated hotels at spring training, ending that practice only four months before the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act was passed? Why should Griffith, once quoted as telling an all-white Lions Club gathering that he’d relocated the Washington Senators to the Twin Cities in ’61 because he’d “found out you only had 15,000 Black people here,” continue to preside over a partially-taxpayer-funded stadium, outside a ticket entrance named after Twins legend Rod Carew, who is Black, and whom Griffith’s own comments alienated and drove out of town?

“We’re asking for very little,” says Tucker. “We’re not asking for, like, a meet-and-greet with the players. We’re asking to be accounted for as representatives of the community. We weren’t welcome when this guy was around—so now he’s not welcome when we’re around.”

***

Growing up in Duluth, two hours north of Minneapolis, Tucker fell hard for the local team after they won the 1987 and ’91 World Series. Soon he was sporting an oversized WORLD CHAMPIONS hat, wearing his Twins sweatshirt until the lettering wore off, taping every game on television. He still records games, even though he hasn’t attended one himself in five years. “You never get over your first love,” he says.

It was love that Tucker recalls feeling in 1991, cheering from home as Jack Morris went 10 innings to beat the Braves in Game 7 and capture another Series. “That was the pinnacle,” he says. It was love that lured Tucker to devour every baseball book at his school library, memorize the trading card stats of every Twins player and buy “whatever magazine I could get my hands on” to learn about the top prospects in Minnesota’s farm system. And it was love that ultimately drove Tucker to leave Duluth in 2005 and relocate to Minneapolis, where he works today as a hospital registrar during the coronavirus pandemic. “The big reasons I came down were to watch [former Vikings receiver] Randy Moss in person and to go to Twins games,” he says. “Then Randy Moss got traded, and I found out the Twins had a racist statue.”

Griffith’s likeness has loomed at Target Field since the stadium opened in 2010, but Tucker didn’t know anything about the white man behind the bronze until ’15, when he read a Vice.com article headlined “Why the Twins Should Tear Down Their Statue of a Former Owner.” There he learned about the Lions Club incident, and the weak rebuttal Griffith issued in his defense, telling the Star Tribune: “What the hell, racism is a thing of the past. Why do we have colored ball players on our club? They are the best ones. If you don't have them, you're not going to win." Clicking to another story, Tucker learned, too, about how Carew had reacted in disgust to those remarks before forcing a trade to the Angels in 1979. “I will not come back and play for a bigot,” Carew declared. “I’m not going to be another n----- on his plantation.”

At first, Tucker was conflicted. “I was like: Surely, whoever put this statue up, they didn’t know [about the details of Griffith’s past],” he says. But it didn’t take long to realize: “I figured it out by a simple internet search—the Twins obviously had way more information as to who [Griffith] was and what he stood for.” His boycott began then and there. “They let me and a lot of their fans down,” he says. “It’s like when a family member betrays you. You’re hurt, but you’re more disappointed than mad. Had I not loved the Twins so much, I probably wouldn’t care.”

For years, Tucker struggled to get others behind his cause. His younger brother Scott agreed to end their longtime tradition of catching a Fourth of July–weekend ballgame in Minneapolis together—“Really wanted to go, but have to support the cause,” Scott says—but even those in Tucker’s inner circle seemed to struggle in understanding why he’d quit cold turkey on the team. “Mostly they laughed,” he says. “One friend was like, ‘I’ll buy your ticket!’ Well, no, that’s not the point.”

Still Tucker stayed away. In June 2017, one day after a police officer was acquitted of manslaughter charges in the killing of a Black civilian named Philando Castile, Tucker posted on his Facebook page:

"I wonder if anyone else notices the irony of the Cleveland Indians visiting Target field on the same weekend a law enforcement officer gets away with unjustified murder. Cleveland has a racist logo and a team nickname that has been considered politically incorrect and derogatory for decades. While playing in the #Mntwins ‘state of the art’ stadium, that has a statue of a documented racist, former owner Calvin Griffith, outside of it."

Now that more supporters have come around, Tucker has accelerated his efforts to get the Twins to take notice. Through the Facebook group, an email campaign was organized, flooding the team’s community relations department with demands to take down the statue before the start of the delayed 2020 season (whenever that is). Between shifts at the hospital, Tucker keeps busy by reaching out on social media to current and former players—“Torii Hunter on Instagram and Twitter; Max Kepler on Instagram; Miguel Sano, Byron Buxton, Eddie Rosario,” he says, to name a few—sharing the bullet points about Griffith’s past and asking them to consider taking a stand. “Sooner or later,” he says, “someone will catch wind of this. Like, if we had Torii Hunter sign the petition, I think that might go a long way.” (A message left at Hunter’s agency was not returned.)

Hunter is Tucker’s unquestioned all-time favorite Twin, though he does reserve a special place for another one of the franchise’s star center fielders. As a child, Tucker didn’t just worship Kirby Puckett for his World Series heroics, or for how downright relatable the star outfielder looked with a bat in his hands. “His body type,” Tucker says. “He shouldn’t be good at baseball.” There was also the simple fact that Puckett looked like him and his family. “There weren't a lot of Black people in Duluth, and I was the only one of my Black friends who liked baseball,” Tucker says. “The minority and people of color players the Twins have had, I’ve always been the biggest fans of them.”

Which is why the statue bothers him and others so much. They see a dissonance between Black players who have carried the Twins—including Carew, Puckett, Hunter and, most recently, Gold Glove winner Byron Buxton—and the team’s continued association with Griffith. They wonder how the team squares the Pohlad family’s recent commitment of $25 million to Twin Cities racial justice efforts with the man memorialized outside its front gates. “It’s important for the Twins to take a stand, reach out and show that they support the community,” says Scott Tucker. “The Twins [posted] something about standing with Black Lives Matter, but it’s kind of hypocritical to say that and have their statue remain, knowing his character. People want to say, he’s the first Twins owner, he brought the team to Minnesota, he deserves to have a statue. I get that history, but I think the more important history is what he stood for. I don’t think monuments like that should be standing in the first place.”

In idolatry, as in physics, what goes up tends to come down, anyway. Human history is littered with the remains of once-glorified statues that fell amid wider societal change. In 1776, colonial Americans toppled a statue of King George III and melted the metal into bullets for the Revolutionary War. Some two and a half centuries later, monuments to Columbus and Confederate leaders are crumbling across a country that was long ago seized from Native Americans and subsequently built on the backs of Black slaves. This is not history being silenced; these statues were erected to silence the memories of the people whom they loomed over in the first place. Rather, it is simply history running its course, evidence of what can happen when enough voices come together to demand a better future.

***

Through Thursday night, according to Tucker, no Twins players or front-office officials had gotten back to him, despite his many overtures. One member of his public Facebook group, though, did post a brief reply from the Twins’ manager of community relations and youth engagement, Josh Ortiz: “Thank you for sharing your thoughts. I have sent this to the appropriate people in our organization.”

While Tucker waited, he was already mulling over next steps for the campaign. More emails and messages, for sure. Perhaps a peaceful protest at the statue, just like the two he attended outside Minneapolis police precincts in Floyd’s memory. “I don't care if it’s only five of us, 10 of us,” he says. “I just want them to give a statement saying how they really feel about this. I’m giving them the benefit of the doubt. Somebody in the organization, their heart has to be in the right place.”

On Friday, the 155th anniversary of the official end of slavery in the United States, Tucker’s years of persistence were, if not outright acknowledged, then nonetheless rewarded. In announcing that Griffith’s statue had been removed earlier that morning—around the same time that a monument to segregationist and former NFL owner George Preston Marshall was taken away from Washington’s RFK Stadium—the Twins issued a statement that included the following:

"While we acknowledge the prominent role Calvin Griffith played in our history, we cannot remain silent and continue ignoring the racist comments he made in Waseca in 1978. His disparaging words displayed a blatant intolerance and disregard for the Black community that are the antithesis of what the Minnesota Twins stand for and value.

Our decision to memorialize Calvin Griffith with a statue reflects an ignorance on our part of systemic racism present in 1978, 2010 and today. We apologize for our failure to adequately recognize how the statue was viewed and the pain it caused for many people—both inside the Twins organization and across Twins Territory. We cannot remove Calvin Griffith from the history of the Minnesota Twins, but we believe removal of this statue is an important and necessary step in our ongoing commitment to provide a Target Field experience where every fan and employee feels safe and welcome.Past, present or future, there is no place for racism, inequality and injustice in Twins Territory."

Now that his boycott is officially over, now that he can watch his beloved Twins in person again, Tucker knows what he’s going to do. First, he wants to email “the powers that be for the Twins and let them know, I appreciate it, and the city appreciates it,” he says. Next he will make the two-mile trek from his apartment to Target Field to bear witness to the empty spot where the bronzed bigot once stood.

“Then I plan on buying a Buxton jersey,” he says. “I can’t wait for Opening Day.”