This postseason has all the makings of a blockbuster, starting with a win-or-go-home epic between the Yankees and Red Sox. Anything can happen.

Consider this your operating system update. Put your pager away and stop looking at postseason baseball like it’s the 1980s. As much as we hype starting pitchers, and swoon over those rare games when they seem to put their team on their back, postseason baseball more than ever is decided by bullpens—and the managers who run them.

In the 1980s, starters accounted for 67% of postseason wins. Last season that rate dropped to 51%.

What about the team that won it all, the Dodgers? They had Clayton Kershaw, Walker Buehler, Dustin May, Julio Urías and Tony Gonsolin to start games, right? Was not starting pitching the key to Los Angeles’s winning the World Series? Not nearly as much as you think.

The Dodgers played 18 postseason games. Their starters won seven of them. Their bullpen picked up six.

Dodgers starters pitched more than six innings just once in 18 starts. They went through the lineup three full times just once. The Dodgers and Red Sox (2018) won two of the past three titles with a starter going three times through a lineup once in 34 combined starts.

Think about this: When was the last time a manager was roasted for leaving a pitcher in a postseason game too long? Grady Little in 2003? Managers are unfailingly aggressive when it comes to pitching changes. The numbers tell them to trust a fresh arm over a (potentially) tiring one.

Starters last year were much more likely to lose a postseason game than win it (27–35). They have become “game managers”—keep the team in the game one or two times through the lineup. Just don’t lose the game.

Wendell Cruz/USA TODAY Sports

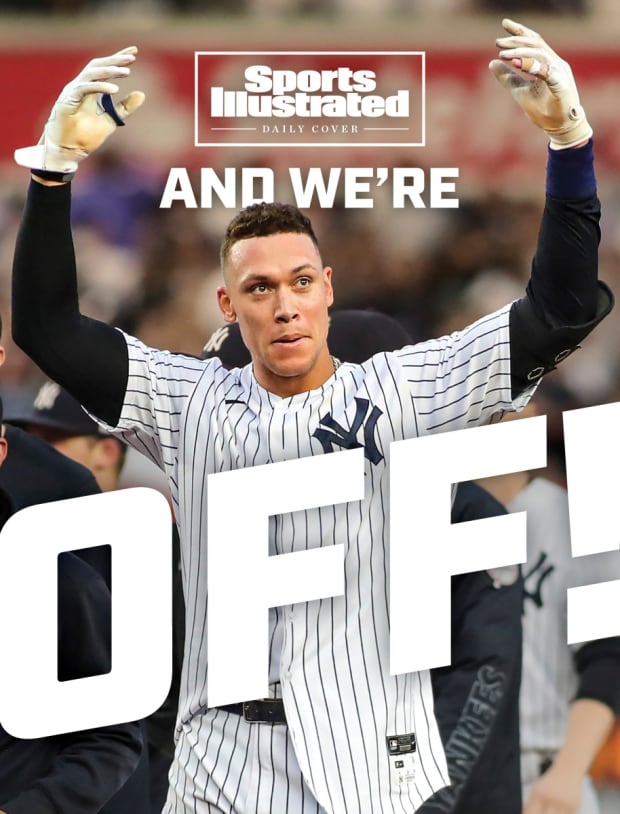

This postseason has all the makings of a blockbuster, starting Tuesday with a win-or-go-home, shades-of-’78 epic between the Yankees and Red Sox at Fenway Park.

This postseason also features a defending champion trying to end baseball’s record 20-year drought without a successful title defense. Three teams that won 100 games (Giants, Dodgers, Rays). Five of the six franchises that have won the most World Series titles: the Yankees (27), Cardinals (11), Red Sox (9), Giants (8) and Dodgers (7). Two teams, the Rays and Brewers, that have never won one.

Anything can happen. But the most likely scenario is that bullpens, and the managers that run them, will play a major role in deciding games and the next world champion.

With that update downloaded, here are some other key questions about this postseason:

Who are the most aggressive managers?

1. Craig Counsell, Brewers

2. Alex Cora, Red Sox

3. Kevin Cash, Rays

4. Gabe Kapler, Giants

5. Dave Roberts, Dodgers

This year experience matters in the dugout. The least experienced manager in the field of 10 is Cora, who has three years under his belt.

Kamil Krzaczynski/USA TODAY Sports

What is the most fascinating manager matchup?

Tony La Russa of the White Sox (second all-time in wins) vs. Dusty Baker of the Astros (12th). Where to begin? Sept. 30, 1971. Fifty years ago, La Russa and Baker were Braves teammates who played in the same game that one and only time. Each had two hits. La Russa never took another major league at bat.

Fifteen years later, La Russa was hired to manage Oakland, where Baker was playing his last season, which means La Russa and Baker were on the same team when each took their last at bat.

Baker joined the Giants as a coach. La Russa’s A’s beat Baker’s Giants in the 1989 World Series. Baker became Giants manager. Baker’s Giants beat La Russa’s Cardinals in the 2002 NLCS.

Benches emptied in Game 1 of that series over a beanball. The next year, Baker’s Cubs and La Russa’s Cardinals exchanged hit-by-pitches to the opposing pitcher, prompting the managers to yell and curse at each other from their dugouts. And seven years after that, Baker’s Reds and La Russa’s Cardinals brawled over words by Cincinnati second baseman Brandon Phillips.

Two years later, Baker hinted that La Russa snubbed Phillips and Reds pitcher Johnny Cueto for All-Star selections. La Russa called such an inference “a knife in the back.” Shortly after, he wrote in a book—without mentioning Baker by name—that the inference had the effect of “destroying a relationship.”

When they met this year for the first time they shared a handshake and a smile while exchanging lineup cards with the umpires.

Fifty years after that professional relationship began, 77-year-old La Russa and 72-year-old Baker renew the rivalry. They have managed against each other 208 times. Each has won 104 times.

Watch MLB games online this postseason with fuboTV: Start with a 7-day free trial!

Is Tampa Bay’s rotation a problem?

No, not in today’s game. Traditionalists may cringe. After all, only Orioles starters threw fewer innings per start (4.6) and no rotation averaged fewer pitches per start (73). No Tyler Glasnow and Blake Snell this year. But in the postseason last year, Glasnow and Snell pitched less than six innings 10 times in 12 starts.

The Rays used five or more pitchers in a game this year 69 times. They were 43–26 in those games. Actually, no team plays this Johnny Wholestaff game better than the Giants, who out-Ray the Rays with the depth of their staff on a game-by-game basis. The Giants used five or more pitchers 84 times and went 53–31 in those games.

Benny Sieu/USA TODAY Sports

Why are the Brewers so dangerous?

There are fewer hits in a game today than in any full season since the mound was lowered in 1969. Batting average is the lowest since the DH was established in 1973. What that means is that stringing hits together is rare, so as a pitching staff you must limit free bases (walks) and quick strikes (home runs). To do that you need pure stuff. And the best way to measure pure stuff is how a team limits slugging on pitches in the strike zone.

Minimizing slugging percentage on pitches in the zone is so important that each of the eight best teams at doing so made the playoffs. The only ones outside the top eight were the Yankees (10) and Red Sox (15).

Recent world champions that depressed slugging inside the zone were the 2020 Dodgers (first), '18 Red Sox (sixth), '16 Cubs (first) and '15 Royals (seventh). And that brings us to Milwaukee.

The Brewers ranked second in lowest slugging allowed on pitches in the zone (.427). Corbin Burnes (.338), Brandon Woodruff (.354), Freddy Peralta (.358), Jake Cousins (.310) and Josh Hader (.244) have the stuff to get hitters out in the zone, which plays up in the postseason, when getting hitters to chase or out-finessing teams becomes harder.

The only team with better stuff in the zone was the Dodgers, again, and by leaps and bounds (.406). But the Brewers’ elite stuff is missing one key arm, which raises the next question:

David Kohl/USA TODAY Sports

What are the most important recent injuries?

Just about every postseason team had to overcome injuries this year (i.e., Ronald Acuña Jr. of the Braves, Glasnow of the Rays, Jordan Hicks of the Cardinals, etc.). But the last week of the season saw several key injuries that could affect the postseason. Here are those injured players in order of biggest potential impact:

1. Devin Williams, Brewers

2. Max Muncy, Dodgers

3. Brandon Belt, Giants

4. DJ LeMahieu, Yankees

5. J.D. Martinez, Red Sox

6. Clayton Kershaw, Dodgers

What type of offense wins in the postseason?

No, the answer is not small ball. With so few hits in a game, home runs account for a larger percentage of scoring. It’s difficult to find one stat that decides who wins or loses a playoff game more than this: out-homer your opponent. Teams that out-homered their opponent last postseason were 34–5 (.872).

The next best thing to out-homering your opponent is hitting a second home run. Going back to 2015, the unofficial start to the Three True Outcomes Era, winning percentage in the postseason goes up 192 points upon the second homer, from .471 to .663. The proof of the impact of home runs in the postseason:

Postseason Outcomes by Home Runs Hit, 2015-20

How does it apply this year? The Yankees seem scary with their Jumbo Package of Aaron Judge, Giancarlo Stanton and Joey Gallo. But they can be streaky and are strikeout-prone. The home run advantage is another edge for the Giants, who have a ground-ball staff and fly-ball hitting offense and are more likely to out-homer opponents than any other team.

Home Runs Hit vs. Allowed, 2021 Postseason Teams

Any advice for managers?

Run on the closer. Stringing hits together off a closer is extremely difficult. For instance, Kenley Jansen of the Dodgers pitched 69 times this year. He gave up zero hits or one hit in 61 of those 69 games. Playing for three singles is foolish. You must turn singles or walks into doubles by stealing second base. The odds are much better.

Here are the closers most vulnerable to the stolen base:

Who will be the Randy Arozarena of this postseason?

Reliever Camilo Doval of the Giants is a breakout player waiting to happen. With just 29 games and three saves under his belt in the big leagues—and with a filthy two-pitch mix with deception—Doval, 24, has a chance to be to this postseason what Francisco Rodríguez was to 2002 (5–1 in 11 games). The Giants play baseball like the Rays, which means Kapler will use his best relief arms without a formula. Doval, not just Jake McGee, could end up closing games.

Brad Mangin/Sports Illustrated

A former shortstop signed for $100,000, Doval has a whip-like, if stressful, arm swing. (His forearm drifts far from his head, putting the arm in a loaded position greater than 90 degrees, which can stress the shoulder.) His low release point (5.43) and velocity (98.6) are near statistical twins of Jacob deGrom’s four-seam fastball (5.49, 99.2)—only Doval’s heater has more spin. And that’s not even Doval’s best pitch: that would be a slider that he throws 12 mph slower with nasty downward bite that calls to mind the slider of Brad Lidge. He has true closer’s stuff.

Two years ago, he was in A-ball walking 34 batters in 56 1/3 innings. Last year he did not pitch competitively because of the pandemic. Now he may be asked to get some of the biggest outs for the winningest team in Giants history.

Wait, what about Wander Franco?

I assume that by now the Rays’ rookie infielder is a known quantity. He plays like a veteran. He does have the swing, approach and calmness to exceed in postseason pressure situations. Franco is an elite breaking ball hitter (.296, 15th best in MLB) who rakes against relief pitching (.327) and late in games (.387 after the sixth inning), doesn’t swing and miss much, and keeps getting better. In 50 games since July 22, Franco is hitting .323/.382/.502.

Kim Klement/USA TODAY Sports

How dangerous are the Astros?

They are being overlooked as strong potential World Series winners. The bullpen will decide how far they go. Houston’s pen has the highest ERA of any postseason team (4.06) and the second most losses (31, two fewer than Atlanta). But the veteran lineup knows how to play postseason baseball. Yuli Guriel and Carlos Correa are the two most improved hitters in baseball when it comes to chase rate.

If there is one stat most in Houston’s favor, it is this: The past four World Series winners all ranked among the four toughest teams to strike out. This year, Houston is the only playoff team to rank in the top six in lowest strikeout rate.

Past Six World Series Champions

But if we include teams that reached the World Series, the tough-to-strike-out theme loses some of its strength:

Past Six World Series Losers

So how does it all end?

As much as we have come to believe that the postseason is a crapshoot, seven of the past 12 World Series teams led their league in wins during the regular season. The best teams are getting through more often than not.

This year the Giants and Rays led the NL and AL, respectively, in wins. They also have home field advantage, they hit home runs, they have aggressive managers, and they have deep bullpens to gain as many batter-pitcher matchup advantages as possible. That makes them the teams best equipped to navigate the updated version of postseason baseball.

Sign up for our new MLB newsletter: Five-Tool Newsletter.

More MLB Coverage:

• Expert Predictions: Who Will Win the World Series?

• MLB Power Rankings: Sizing Up the Postseason Field Ahead

• The Blue Jays Build Up Some Scar Tissue

• Will the Cardinals' Hot Streak Matter in the Playoffs?

Read more of SI's Daily Cover stories here

Sports Illustrated may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website.