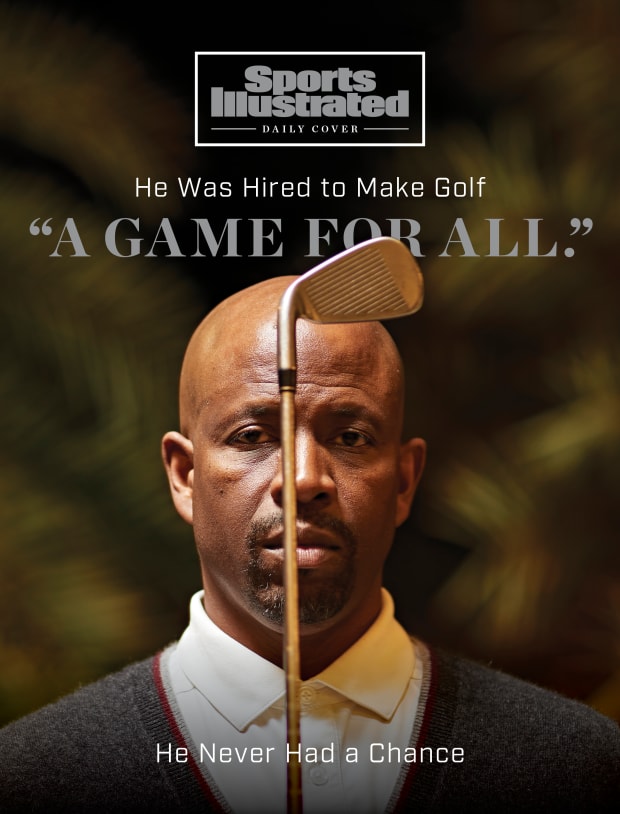

The PGA of America hired Wendell Haskins to make golf "a game for all." He never had a chance.

Barack Obama leaned over and gently fastened the blue ribbon around the 92-year-old man’s neck. This was November 2014, and Charlie Sifford, who was once denied the opportunity to compete on the tour of the Professional Golfers’ Association because of his skin color, was at the White House.

Alongside the family members and dignitaries in the East Room that day was a man named Wendell J. Haskins. This was the moment Haskins had been intent on making happen since he was hired earlier that year as the PGA of America’s new senior director of diversity. It was not easy: He had worked a connection with Alonzo Mourning, who he knew occasionally golfed with the president, asking the former NBA All-Star to plant the seed during a round with Obama. Haskins then spent months collecting dozens letters of support for Sifford from the likes of Arnold Palmer; Jim Brown; Samuel L. Jackson; South Carolina Rep. James E. Clyburn and 63 other bipartisan members of Congress; and Tiger Woods, who wrote that Sifford “helped pave the way for players like me.”

Now, the nation’s first Black president was awarding the Jackie Robinson of golf—the first Black man to compete on the PGA Tour—the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Robinson’s widow, Rachel, had been among the letter writers. Sifford, who once said he rarely smiled as a result of the discrimination he’d endured through his life, beamed.

But there was just one problem: None of the PGA of America’s senior leaders had come to Washington to celebrate Sifford. When it came to bringing racial awareness to golf—and reckoning with the sport’s racist and exclusionary history—Haskins had found it easier to get the ear of the President of the United States than the people he worked with at PGA headquarters.

In a July 2014 email, then PGA of America chief administrative officer Christine Garrity wrote that it was not appropriate for the group to “take credit” for the Sifford initiative “as it should be postured as a collective movement of many organization[s] and people.” She additionally cited the PGA of America’s history of racism and Sifford’s assumed but unconfirmed bitterness toward the organization as a reason to not acknowledge the efforts. “It’s also important to remember history, and it was the PGA that denied Mr. Sifford membership in the organization until 1962, so there is bitterness from Mr. Sifford toward the PGA and the PGA TOUR (rightfully so) that is still palpable for Mr. Sifford,” she continued in the message, reviewed by Sports Illustrated. (Garrity left the PGA of America in 2015; she did not respond to requests for comment.)

Even if Garrity’s goal was to share credit, though, Haskins says the upshot was a missed opportunity to make amends for the PGA of America’s history of mistreating Sifford. Haskins had wanted to plan a reception around the medal ceremony, which he saw as an opportunity for the PGA of America to forge a stronger connection with the Black community, but was restricted in his efforts. He says that another PGA colleague, Sandy Cross, now the organization’s chief people officer, told him that this was not the time to be planning a party for his friends. (The PGA of America did not make Cross available for an interview.)

Meanwhile, Haskins says the board also denied his petition to expedite Sifford’s candidacy for the PGA of America Hall of Fame. Sifford, who died two months after the medal ceremony, was inducted into the Hall posthumously.

Seth Waugh, who became the PGA of America’s CEO in 2018, said he could not comment on the handling of specific incidents or decisions that were made before he joined the organization. (The PGA of America is a separate entity from the PGA Tour; it oversees the 29,000 golf professionals who work at courses across the country while pursuing its mission to grow the game. The PGA of America also hosts and organizes some tournaments, including the PGA Championship.)

This summer, as sport after sport went through some form of racial reckoning in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, Haskins watched as golf barely took the time for a glance in the clubhouse mirror. What he did see from the PGA of America seemed like it was only surface-level. It brought him back to the neglect and disinterest he says he experienced in his nearly four years working there, and he felt compelled to lay it out on paper. On June 12, he wrote a letter to Waugh and the association’s president, Suzy Whaley.

I find it necessary to share this with you in the hope that it will help you in understanding the culture of your company and taking the courageous and necessary actions to make the PGA of America a truly diverse and inclusive organization.

Haskins’s letter, which he also posted publicly, sent waves through the golf world. Over six pages, he laid out a detailed list of issues and hurdles he says he faced while with the PGA, which he elaborated on to SI, providing emails and other documentation to back his claims. “This isn't just a PGA of America problem,” says Haskins, 53. “I've worked at the PGA of America, but it's the golf industry that has a problem. My experiences were a reflection of a larger issue.”

All of which raises the central question, as the golf world once again descends on the famously restrictive Augusta National: Is golf finally ready to reckon with racism within the sport?

* * *

More than any other tournament, the Masters reminds us that golf’s history cannot be separated from its present. Its legend is largely built on the exclusivity of a club that did not admit a Black member until 1990 and a female member until 2012. Sifford was never invited to play in the tournament, despite his two PGA Tour victories after breaking the color barrier in 1961; not until 1975 did Lee Elder become the first Black golfer to compete at Augusta National.

Woods has more than made his mark at Augusta, but his ascension to the top of the sport hasn’t created the pipeline of Black golfers that many had hoped. He and Cameron Champ are the only two Black competitors in this year’s Masters field, joining Harold Varner III and Joseph Bramlett as the only four Black full-time PGA Tour members; Mariah Stackhouse is the only Black full-time LPGA Tour member. Renee Powell, who in 1967 became the second Black woman to play on the LPGA Tour, describes a “regressive” trend, recalling there being about a dozen Black golfers playing the Tour in the ’70s, many of whom entered the game as caddies.

The PGA of America has similar representation issues: Only 174 of its 29,000 golf pros are Black—about half of a percent—per the association. “Not a good number,” Waugh says. The association also says it does not currently have any Black C-suite-level executives working at its headquarters. Haskins believes the experiences he has shared, as one of the few Black executives to work for the PGA of America, are not specific to one workplace or entity—rather, they are common to the culture of the sport he loves. But they stood out at a governing body with a stated mission of growing and advancing the game.

After growing up in northern New Jersey, Haskins began playing golf in the late ’90s, when he was a young professional living in Brooklyn and working as a director of artist development for Island Black Music. His father gifted him a used set of Ben Hogan graphite shaft irons, and he started going to Chelsea Piers’ driving range to learn how to play in time to join a golf trip with a mentor, Michael Vann, an entrepreneur who owned a popular New York soul food restaurant called Shark Bar. Haskins struck up a friendship with a Black teaching professional at the driving range, trading CDs for extra time in one of the hitting stalls. Later, as he mastered the game’s fundamentals, he’d play Brooklyn’s Dyker Beach Golf Course early on weekday mornings before heading into Manhattan for work.

Haskins fell in love with how the sport presented endless playing possibilities at courses all over the world. It wasn’t until he read the book Forbidden Fairways, though, that he began to understand the depths of the game’s complicated history. The author, Calvin Sinnette, opens by explaining how a Black dentist named George F. Grant patented the first wooden golf tee in 1899. His invention came a quarter-century before that of William Lowell, the white dentist in New Jersey who was for decades recognized as the tee’s inventor.

This moved Haskins to create, in 2000, a golf tournament celebrating the unheralded history of Black golfers. He named it the Original Tee. He started consulting for the NBA around this time, helping produce commercials and the All-Star Game halftime show, which connected him with greats like Julius Erving and George Gervin, who loved to play golf. These connections in sports and entertainment helped the Original Tee grow into an annual gathering of influential members of the Black community, where emerging Black golfers had the rare chance to play in front of a mostly Black gallery at New Jersey’s Crystal Springs Resort. He drew Erving, Doug Williams, Anthony Anderson and Luther Campbell; he honored Sifford and Elder years before he pushed golf’s establishment to do so. “We have to stop, particularly white people in golf, seeing this as Black golf history,” Haskins says. “It’s American history.”

All of this led to Haskins’s being hired by the PGA of America in 2014. Then CEO Pete Bevacqua said at the time he wanted Haskins to use his connections “to make golf a game for all.” But working on diversity and inclusion efforts for a governing body that held a “Caucasian-only clause” as part of its bylaws for membership until 1961, 14 years after Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers, posed challenges that Haskins did not need to explain when he described the opportunity to people close to him. “Are you ready to be part of firsts?” Erving says he asked him. “If you’re not, step back and let someone else do it. But if you are ready, then go after it.”

In many ways, Haskins had been preparing for this role for most of his life. His father, Bill Haskins, was one of the first Black football players at Syracuse, suiting up at running back a few years before Jim Brown arrived. Haskins recalls his father recounting to him what happened when he arrived at his dormitory, trunk in tow, as a college freshman in the late 1940s: “Nobody told me a [n-word] was going to be staying in this dorm,” the resident adviser said to him. William later went on to be an executive for the National Urban League, where Wendell grew up playing under the desk of civil rights activist Vernon Jordan.

All of this was on Haskins’s mind this summer, in the days following the release of video of a white Minneapolis police officer kneeling on a Black man’s neck until well after he stopped breathing. During the days of protests that followed Floyd’s killing, millions of Americans demanded that our country, and its institutions, confront racism. Haskins thought about what his father told him when he took the job at the PGA of America, drawing on his own experience fighting for Black Americans: Don’t be scared. Bill, who had had Alzheimer’s, died three months later, leaving these words as an enduring directive for his son. And so, Haskins opened his Original Tee letterhead, and he began typing.

* * *

Haskins wrote his letter just a couple of miles from the PGA of America headquarters in Palm Beach Gardens, Fla., where he still lives with his wife and three sons. Now the chief marketing officer of the Professional Collegiate League, he never intended to share publicly the details of his tenure at the PGA from January 2014 to September 2017. But as he encountered what he describes as resistance to doing the job he was brought in to do, he started filling a notebook and keeping printouts of emails in a desk drawer. He drew from this record of his experiences as he sat down to write his letter.

There were myriad microaggressions, unscrupulous practices and instances where the PGA could have stepped up, stepped in or merely showed up to improve race relations and did not.

Haskins’s Original Tee Golf Classic paved his opportunity with the PGA of America, and, by the time he arrived, the tournament was a well-oiled machine. But a few months after he started at the association, Garrity, the chief administrative officer and his supervisor at the time, advised him to postpone or cancel that year’s event, suggesting it could be held in conjunction with the PGA’s Minority Collegiate Championship the following year, subject to the association’s approval of his business plan. In an email reviewed by SI, Garrity wrote that planning had started too late to meet the PGA’s “quality standards,” and, if Haskins did go forward, he must not use any PGA affiliation or collaborate with PGA staff for the event. “These are all busy people and it’s important for them to disengage from the event this year and focus on other matters at this point,” she wrote. Haskins continued on his own with the 14th year of his tournament, which that year honored Powell and counted the NBA and Mercedes-Benz among its sponsors.

During his first year at the PGA of America, Haskins connected through a mutual friend with Kevin Clayton, the former chief diversity officer of the USTA, to seek his input on developing a diversity and inclusion plan for the PGA of America, designed to position these efforts as also good for business. But Clayton soon became alarmed by what he saw as a lack of support for Haskins, who did not control a budget. “I have never seen the blatant sabotage that Wendell went through,” says Clayton, now the VP of diversity and inclusion for the Cleveland Cavaliers. In July 2014, another executive, Cross, was appointed to the same role Haskins was hired for and designated to be what he describes as his “peer supervisor.”

Despite early hurdles, Haskins hoped his work to honor Sifford would be a turning point for the PGA of America with the Black community. He emailed Garrity suggesting the association hold a reception the day of the White House ceremony and invite the people who penned letters of support for Sifford, describing this as “a key opportunity to message this very influential group and establish deeper relationships with them that can help drive the mission of the department.” Garrity replied, in an exchange read by SI, that she did not think guests would be motivated to travel for a reception, “unless I’m missing something.” Haskins says Cross, who was the person who told him it was not the time to plan a party for his friends, instructed him to return travel vouchers he’d secured from Delta for this purpose.

“I had always envisioned this would be a watershed moment for golf, where people would recognize this Black man for his contributions to the game,” Haskins says. “The PGA of America president and CEO would come and shake his hand and tell him, Thank you for what you did for golf. … I've seen the things they do and how they celebrate their successes at the PGA. If it was Jack Nicklaus, or somebody like that, the budget would have been wide open.”

Ultimately, Haskins organized a small private dinner for Sifford the night before the White House ceremony. Anthony Stepney, the first Black golfer to earn the PGA’s high-ranking master professional status, worked with Clyburn and now-late Rep. Elijah Cummings to host a larger reception of about 150 people at the U.S. Capitol after the medal ceremony. This was funded by a private donations, Stepney says; the PGA of America had no involvement, and no leadership attended. Since the airline vouchers had already been issued, instead of returning them, Haskins passed them to Stepney to invite a handful of guests, including Varner, then an up-and-coming golfer, and now one of the four Black full-time PGA Tour members. Stepney says that, had he not been so committed to his work in golf, the PGA of America’s resistance during the planning of the Sifford festivities could have been enough to discourage him from being a member.

“There were some decision-makers within our association that unfortunately didn’t understand the value of diversity and inclusion and equity,” Stepney says. “This is a great example of what happens when we lack diversity in decision-making: We miss out on opportunities, and we are guided by our limitations, our blind spots and maybe fear or lack of understanding.”

As for Sifford’s presumed bitterness, cited by Garrity in her email: Haskins and Stepney say that no such feeling was conveyed by Sifford or his family during their efforts to honor him. The 92-year-old mingled late into the evening with those who had traveled to D.C. for him. In the final months before he died, Sifford woke up every Sunday morning before church, got dressed and put on the medal he’d received from the president.

Haskins later shifted to a different role within the PGA, director of sports and entertainment marketing, but says he continued to encounter roadblocks. In 2016, he says that a senior director of media was hesitant to air a commercial he’d worked on, featuring Chris Paul and his family playing golf with a PGA pro, saying it was “too different.” The commercial did ultimately air prominently during the Golf Channel’s championship coverage. The following year, in 2017, Haskins spent several months building a relationship with Warriors star guard Steph Curry. “The golf industry is so monolithic in their thinking. They only market the game for the most part with professional golfers,” Haskins says. “I was trying to change that with guys like Steph Curry and Chris Paul, who love the game and have so much influence on a new demographic of people.”

Haskins leaned on his NBA contacts to introduce him to Curry after a game in Cleveland during the 2017 Finals. Later, Haskins says Curry’s camp offered a meeting with him in Oakland to discuss his becoming an ambassador for PGA Junior League Golf. But in August 2017, while attending the PGA Championship at Quail Hollow Club, Haskins received a discouraging phone call: PGA chief commercial officer Jeff Price, he says, told him to reschedule with Curry because Price couldn’t make the meeting. Haskins says he soon learned Price rebooked through Curry’s reps without him, cutting Haskins out of a relationship he had initiated. The following year, Curry was announced with soccer star Alex Morgan as the first two ambassadors who were not professional golfers; Price was quoted in the release saying that Curry would help youth golf reach a new audience. (The PGA of America did not make Price available for an interview.)

Haskins’s feelings of being marginalized and not having the chance to close an important deal rushed back to him this summer. Amid the national calls for change following Floyd’s death, Waugh and Whaley both wrote open letters, condemning racism and promising to take actions to make change. An email address for ideas was distributed to PGA members: Inclusion@pgahq.com. One news story Haskins read, on Golf Digest’s website, used a photo of Waugh and Whaley standing with Curry at a joint charity golf event between the PGA and Curry’s foundation.

“It takes me back to a Black person doing the original work, and then a white guy being able to get the credit for it,” Haskins says. “That’s really what made me write that letter.”

* * *

One evening in 2016, Haskins headed to Abacoa Golf Club, a public course not far from the PGA headquarters, to play nine holes after work. A young employee soon drove up in his cart and asked whether he could join Haskins. About six holes in, Haskins noticed a tag on the golf bag of the staffer, who was white: “Young N---- Wilson.”

Haskins says he asked about the meaning of the tag, and the employee explained he was given that nickname and the label by a PGA pro at the club, because he was the rookie in the cart barn. Haskins quietly took a photo of the tag, which he has shared with SI, before they parted ways. Haskins says he sent a detailed account of what had happened to senior leadership at the PGA of America, and they apologized and told him they would address it. As far as he knows, no actions were taken, and he has never learned whether the staffer's explanation that it was a PGA pro who affixed the label was true.

“We were never contacted by PGA of America or anyone else,” says Rob Young, the owner of the Jupiter, Fla., course. “If we had been made aware of this incident at the time, it would have been investigated, as I do not condone the actions described by Wendell, nor do my business partners or the management of Abacoa Golf Club.”

Says Waugh, “I certainly would have made a call if that had happened in my time.”

Waugh adds that he “explored as closely as possible” the incidents that Haskins wrote about in his letter, “events which in some cases may have happened five years ago.” In response to SI’s sending a detailed list of Haskins’s assertions to the PGA for comment, Waugh said, “While we never comment on employee issues, past, present or future, I can say that I am in full support of all of our current employees and the work to make golf and the PGA more inclusive and equitable.”

Haskins had hoped to use his own experiences and conversations with people working at the ground level of the game to broker changes from the PGA of America headquarters. A graduate of Hampton himself, in December 2015, he worked to set up a meeting between a group of HBCU golf coaches and the PGA of America’s chief operating officer, Darrell Crall, along with another executive. The coaches had expressed concerns to him regarding the direction of the PGA’s Minority Collegiate Championship, which was created in the 1980s to be a national tournament for HBCU programs.

Gary Grandison, then the head golf coach at Alabama State, hoped to use the occasion to lobby for more of the money from the tournament’s corporate sponsorships to be directed to support HBCU programs through scholarships and travel reimbursements. Since HBCUs often have smaller funding sources, Grandison says the support of major institutions like the PGA of America is vital for young Black golfers to continue having the opportunity to both play and participate in the networking opportunities the sport provides. The meeting was so important to Grandison that he left his ailing father to make the daylong drive to Palm Beach Gardens.

While the coaches were already en route, though, Haskins learned that both executives had canceled on them. “Why is it when all of these ‘Black’ things come up, it's never a priority?” Haskins asks. While Grandison was driving home a few days later, his father Johnny, who had cancer, died.

Grandison, who now coaches at Texas Southern, decided shortly after that his teams would no longer participate in the tournament because of what he saw as a clear demonstration that the top leadership of the PGA of America did not care about HBCU golf. “I question if growing the game is the real priority of some of our organizations,” Grandison says.

(Crall was not made available for comment; the PGA of America had no additional comment on this incident.)

Three years later, the PGA of America hired a former HBCU coach, Scooter Clark, to manage the tournament and expand its support of HBCU programs. The tournament is now run by an arm of the PGA REACH foundation, which Waugh says is also working to grow the share of children of color participating in its Junior League program to close to 20 percent and the share of girls to about 35 percent. Others in the game point to additional efforts across the sport: This summer, the LPGA created the Renee Powell Grant to support youth golf programs serving Black girls in Powell’s home state of Ohio. And the Advocates PGA Tour, a grassroots effort that is now supported by the PGA Tour, runs golf tournaments and player development programs to provide golfers from underrepresented backgrounds with the resources and the support needed to play at the professional level.

Haskins had hoped to grow the Original Tee under the PGA umbrella as another way to support rising Black golfers. Wyatt Worthington II, who in 2016 became the first Black club pro in 25 years to qualify for the PGA Championship, made more money that year winning the Original Tee’s $16,000 purse. As he continues to pursue his goal of earning status on the Tour, Worthington points out how this pursuit is expensive, from entry fees to travel costs.

“There needs to be so much more representation on Tour,” Worthington says. “If you look at the PGA Tour, it kind of represents the United States in that there are so many white people that have money and power. … I’m just looking for an opportunity to have a chance to make that change.”

Worthington began playing golf at the public driving range in Columbus, Ohio, where his dad hit balls after his shift at a GMC plant, and received a lesson from Woods at age 14, through an opportunity with the First Tee of Columbus. Years later, as his playing career was taking off, he says he encountered his own resistance at the local level. Worthington put in long hours as a caddy at a country club in Ohio, while turning heads at PGA section events, which he prepared for by chipping and putting at his old high school course. When Worthington, one of a handful of Black PGA members in Ohio, was told caddying would not meet membership requirements, he took a job as a teaching professional at The Golf Depot. The year he qualified for the PGA Championship, he says other PGA members began showing up or calling his workplace to check whether he was meeting the weekly hours quota for him to compete as a club pro. “It was such a tale of two sides, because at the same time I had all these people reaching out to me saying you inspired me, or you helped me get back into the game,” Worthington says.

Haskins and Worthington struck up a friendship, and he shared with Worthington what happened that evening at Abacoa. Worthington, who spends his winters working at a golf club in Florida, says he stopped giving Abacoa his business. That led him to playing a different course, about 20 minutes away, in early 2017. As he walked over to put his clubs on a cart, he passed another golf cart and did a double take: sticking out of the top of a pink golf bag were two knit monkey club head covers, next to a Confederate flag.

* * *

In June, a few days after Haskins sent his letter, he and Waugh met for a video call that lasted about two hours. Waugh says he regrets that he had not followed through to connect with Haskins earlier that year, when a mutual connection tried to introduce them. Haskins told Waugh the story behind his Original Tee tournament, and how it helped lead to his writing an open letter.

“I'm not sorry he wrote the letter. Not at all,” Waugh says. “It woke us up on certain points, and a lot of them we're working on and we'll continue to work on.”

The reaction to Haskins’s letter varied. Clayton told Haskins he gave the PGA of America “a gift.” Powell says Haskins’s letter “caused a bit of a stir.” She adds, “It made people think about not just the PGA, but the entire golfing industry.” Another person close to the PGA of America says that some past and present employees waved off Haskins’s experiences as that of a disgruntled ex-employee, but the person added that he nonetheless sparked a necessary internal dialogue. Haskins was surprised to hear from Ted Bishop, the past PGA president who was ousted in October 2014 for sexist comments made in social media posts. Bishop acknowledged the roadblocks Haskins faced and the “good work” Haskins was trying to do.

“I'm not trying to be adversarial to these governing bodies or trying to expose them,” Haskins says. “But if this exposes what already exists and lets them know the ways that they have to be better, then that's what this is for.”

He adds: “You’ve got people who have been hurting over golf for years. Older men, who would be my father’s age, who've been excluded from public golf courses. Black people treated like s--- when they come to enjoy a round of golf with their kid or their friends. People love this game. And unfortunately, it's not the game that hasn't loved them. It's the people.”

Making “atonement” was one of the 11 recommendations included in the final page of Haskins’s letter. Among the others: Establish a seat designated for a Black independent board member, named after Powell and her father, Bill, the first Black man to open and operate his own golf course; hire Black executives at PGA headquarters who control a budget and have decision-making authority, neither of which Haskins had; and be willing to let go of bigots and racist members. In July, the PGA Board of Directors voted to change the name of an award named for Horton Smith, the former PGA president who defended the Caucasian-only clause. This was another prescription proposed by Haskins, as well as others within the PGA.

In July, after the letter, Waugh and Whaley also held two open forums with their Black PGA members—something that Powell, the PGA of America’s only Black board member, says had never been done before. On one of these calls, Stepney says concerns were raised about the 2022 PGA Championship, which is scheduled to be held at Trump National Bedminster. In 2015, after Donald Trump referred to Mexican immigrants as “rapists” while announcing his bid for the presidency, the PGA of America pulled its Grand Slam tournament from his course in Los Angeles but kept its other future events at Trump courses. That same year, Trump told Fortune magazine: “Let golf be elitist,” which some PGA members point out is antithetical to the organization’s stated goal of growing the game.

“Here’s a great example of, listen to your Black PGA professionals,” Stepney says. Waugh confirms these concerns were raised, and says the PGA has “done some thinking about it,” but “we don’t have anything more to say about it at this moment.” Asked whether the input of Black PGA members will be considered in the decision, he adds, “Absolutely. We want to hear all voices. But we have 29,000 of them.”

This week, the Masters are again a symbol for how far golf still has to go in confronting and correcting its racist history. On Monday, though, there was a step in the right direction: Augusta National announced that Lee Elder would be an honorary starter for the 2021 Masters, joining Nicklaus and Gary Player. In Palm Beach Gardens, Haskins received the news with happiness and satisfaction. He’d first suggested the idea six years ago, when he walked in the doors of the PGA of America, not expecting how soon he’d be walking back out.