Fifty years later, the author recalls his bond with Mark Spitz, whose unprecedented Olympic performance was overshadowed by an act of terrorism.

If he’d had a mind to, Mark Spitz could have celebrated on a far grander scale. He could have whooped it up with coaches, teammates and his legion of fans who now were everywhere in Munich. But he wasn’t a party animal, and even on this night of epochal triumph, he wouldn’t become one. Nine days of pressure—actually, four years of pressure—had been lifted from his shoulders, leaving him relieved and happy but with emotions in check. For him, the cobbled-together, late-night dinner at Käfer-Schänke would be celebration enough.

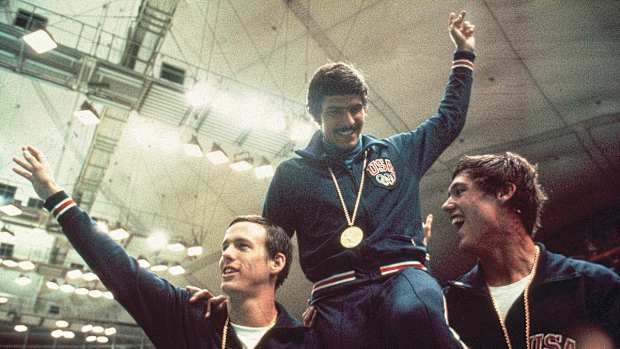

He had ended his athletic career in glory. Shortly after 9 p.m. on Monday, Sept. 4, 1972, 50 years ago, in the final event of the swimming competition at the Munich Olympics, the men’s 400-meter medley relay, Spitz entered the water for the last time. Swimming the butterfly leg, he helped propel the U.S. team to victory, completing a personal feat that redefined perfection: seven events, seven gold medals, seven world records.

Illustration by The Sporting Press; Kurt Strumpf/AP (terrorist); Neil Leifer (police); John G. Zimmerman (Spitz, 2)

Afterward, changed into street clothes and surrounded by well-wishers in a hallway of the Olympic Schwimmhalle, he accepted congratulations, signed autographs and posed for photos. Rakishly handsome, with a recently acquired jet-black mustache set off by a movie-star smile, he obliged the band of photographers who weren’t content until they had captured him from every angle. Finally, as the crush of admirers thinned, he was ready to leave. The tragedy that would befall these Olympics was mere hours away. The Munich Games were about to be transformed, Spitz’s achievements both eclipsed by a murderous attack and fated to be forever twined with it in Olympic history.

In Munich as a writer for Sports Illustrated, I was covering the Olympic swimming competition, which meant, really, that I was covering Mark Spitz. On the Spitz beat with me were two German-born Sports Illustrated colleagues, photographer Heinz Kluetmeier and Olympics reporter Anita Verschoth. We knew Spitz well and he knew us well, and when I invited him to have dinner with us, he accepted. Anita asked around and came up with Käfer-Schänke, a stylish Munich restaurant open during the Olympics until the wee hours. Heinz was bringing a date. It would be the five of us.

Or maybe six. At the last minute, Spitz asked a member of the U.S. women’s team,15-year-old freestyler Jo Ann Harshbarger, to join us. There had been news reports of a romance between the 22-year-old Spitz and Harshbarger, which he laughed off. “I’m too young for Donna de Varona,” he said mock ruefully, referring to an earlier American swimming star who, at 25, had become a grand dame of the sport, “and I’m too old for Jo Harshbarger.” Spitz had a mischievous side to him, and I think he may have invited the teenager mainly to keep the rumors going. Because of the late hour and on the counsel of her cautious minders, Harshbarger declined his invitation. He didn’t seem disappointed.

No plans for dinner until I mentioned it to him? Shot down asking for a date? This was Mark Spitz on this night of all nights. No worries. He was mellow Mark.

It was after 11 when we arrived at the restaurant. Entering, Spitz was greeted by rolling applause. During dinner, free drinks came our way, but he didn’t touch a drop. On other occasions he could be chatty, sometimes overly so, but tonight he went with the flow. All I remember of the evening’s conversation was his asking Heinz questions about underwater photography and telling how he’d gotten a kick out of meeting Duane Bobick, the U.S. heavyweight boxer who later in the week would be knocked out by the eventual gold-medal winner, Cuba’s Teófilo Stevenson. Dinner was leisurely, and time flew by.

With Heinz driving, we dropped Spitz off outside the U.S. compound in the Olympic Village a little before 3 a.m. He was scheduled to hold a press conference at 9 the next morning. I told Mark I’d see him there, and we watched him head for the elevator. It was now Tuesday, Sept. 5.

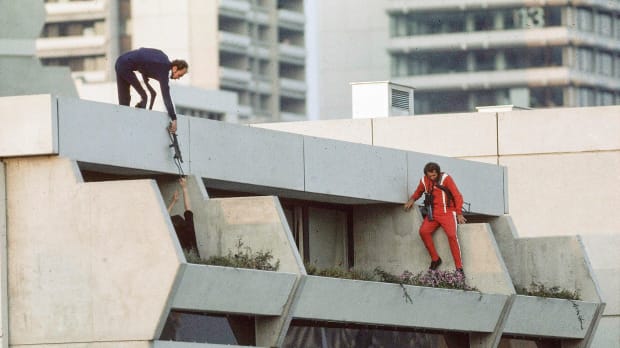

At 4 a.m., very near to where we said goodnight to Spitz, eight terrorists, members of Black September, an extremist arm of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, carrying assault rifles and explosives, scaled a two-meter-high perimeter fence of the Olympic Village. They couldn’t have known how close they had come to meeting face-to-face with the Jewish hero of the Games.

The Palestinians were on a mission that can be summed up with grim statistics: a wrestling coach and weightlifter gunned down in the Israeli quarters in the Olympic Village; nine other Israelis taken hostage; those nine killed along with five of the terrorists and a Munich police officer in a bungled rescue attempt later that night at the city’s Fürstenfeldbruck Air Base.

The Munich massacre shattered what to that point had been a joyous Summer Olympics. For the West German organizers, the Games of the XX Olympiad were intended to put a more humane face on Germany. And they were largely succeeding in that objective. In contrast to the previous Olympics held in Germany, the notorious 1936 Games that glorified Hitler and reeked of racism and antisemitism, the1972 Munich Olympics were friendly, open and relaxed. Perhaps too relaxed.

Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated

Munich also afforded a chance at redemption for Spitz. Four years earlier, at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, as a callow, wise-cracking 18-year-old, he had boasted that he would win six gold medals. Instead, he choked, winning two gold medals only as a member of U.S. relay teams, while settling for a silver and a bronze in individual events. For most other athletes, such a performance would have been hailed as a success, but for Spitz it was seen as humiliation. He was ridiculed by some of his own teammates, who didn’t appreciate his loose lips and what they took to be his me-first attitude.

On arrival in Munich, determined this time to keep his foot out of his mouth, he had announced that he wouldn’t talk to the press during the swimming competition but, win or lose, would hold a press conference after his last event. Reporters bristled at the many times he told them, “no comment.” He may have grown tired of uttering those two words himself.

His press embargo, I was happy to learn, didn’t apply to me. For whatever reason, Spitz seemed to trust me. At 34, I was too young to be a father figure to him, and anyway, he had father enough in Arnold Spitz, a pugnacious man who reveled in his son’s achievements and didn’t hesitate to take full credit for them. But my previous stories about Mark for SI had apparently met with his approval. What I wrote hadn’t always been flattering. I had mentioned his occasional laziness at workouts and his head-spinning swings between braggadocio and bouts of deep insecurity. However, I didn’t dismiss him, as some other writers did, as simply a spoiled brat—at least not in those words.

Something else that may have worked in my favor: Spitz knew that if he shot off his mouth in Munich in front of TV or newspaper reporters, the world would hear about it immediately; because I wrote for a weekly publication, any ill-considered remarks he might make wouldn’t see the light of day until the swimming competition was over.

Often, I was at Spitz’s side. My entrée to him gave me access to much else. If I was challenged by security in the Olympic Village, sponsor tents or restaurants, Mark said, “It’s O.K., he’s with me,” and I was waved through with him. I was his shadow and sometimes his confidante. I knew that reporters aren’t supposed to get too close to their story subjects, and I’ll leave it to the journalism ethics police to determine if I crossed lines.

Well, all right, I know I crossed lines, but I wasn’t wringing my hands about it. For all the negative things Spitz was reputed to be and often was—brash, standoffish, self-centered—I saw him as a sympathetic figure, never more so than in Munich. I thought he was being failed there by some of the elders around him and needed a friend. I can’t say that I was that friend, but at times I acted like I was.

There was even a moment when I might have passed as his press representative. In the days before the Opening Ceremonies, Time planned to put Spitz on the cover of its Olympic preview issue. Faithful to his vow of silence, he declined to be interviewed by the magazine. I had worked at Time before joining Sports Illustrated and was friends with Ray Kennedy, the writer doing the story. Knowing my connection to Spitz, Ray asked me whether I could get him to change his mind.

I saw no harm in putting in a good word for Ray with Mark. I also mentioned to him that making Time’s cover might not be such a bad thing for him and whatever opportunities might await him in his post-Olympics life. He relented, saying he would meet with Kennedy but only if I came along. I said I would, but now it was my turn to stay mum. I said I would be there only for moral support.

The interview took place at mid-afternoon in a mostly empty Munich pub. The three of us sat in a booth under a hanging ceiling lamp, Spitz and I on one side of a wooden table, Kennedy across from us. Mark smoothly answered Ray’s questions. He talked frankly about his disappointments in Mexico City and said of his prospects for success in Munich only that he would do his best. When Ray asked him how he felt as a Jew competing in Germany, Mark was diplomatic. He answered that he wasn’t thinking about Germany’s past. He said he had been warmly greeted by the Munich hosts and had only good to say of the German people. “Actually, I’ve always liked this country,” he said.

Then, on impulse, he lightheartedly touched the lampshade above the table and said, “Even though this shade is probably made out of one of my aunts.” I watched Ray writing furiously in his notebook. The quote, vintage Mark Spitz, appeared in Time’s cover story.

A few hours after our dinner at Käfer-Schänke, I was preparing to depart for the long-awaited Spitz press conference. In the lobby of the Munich Sheraton, where Sports Illustrated staffers and a large complement of other American journalists were staying, I ran into Peter Jennings, a member of the ABC-TV team covering the Games who would one day become the network’s evening news anchor. Peter gave me the shocking news about the two Israelis shot to death and the others taken hostage. There was now, obviously, a bigger story in Munich than Mark Spitz.

As I arrived, the Press Center was filling with journalists anxious to get updates about the terror in the Olympic Village. Soon I saw Spitz entering from a side door with Peter Daland, the head coach of the U.S. men’s swimming team; Don Gambril, an assistant men’s coach; and Sherm Chavoor, the women’s team coach who also was Spitz’s club coach. They were in good spirits.

I walked over to them. Mark thanked me for dinner. “I had a really good time last night,” he said.

“You don’t know, do you?” I could tell that he didn’t.

“Don’t know what?” he asked.

I told them all what little I knew. Spitz was no longer mellow Mark. He said he didn’t want to go before the microphone, where he thought he’d be too easy a target. “They’d just take me hostage—they wouldn’t kill me, would they?” he asked. That may sound like paranoia, but the truth was, at the time nobody knew the extent of the terrorist threat.

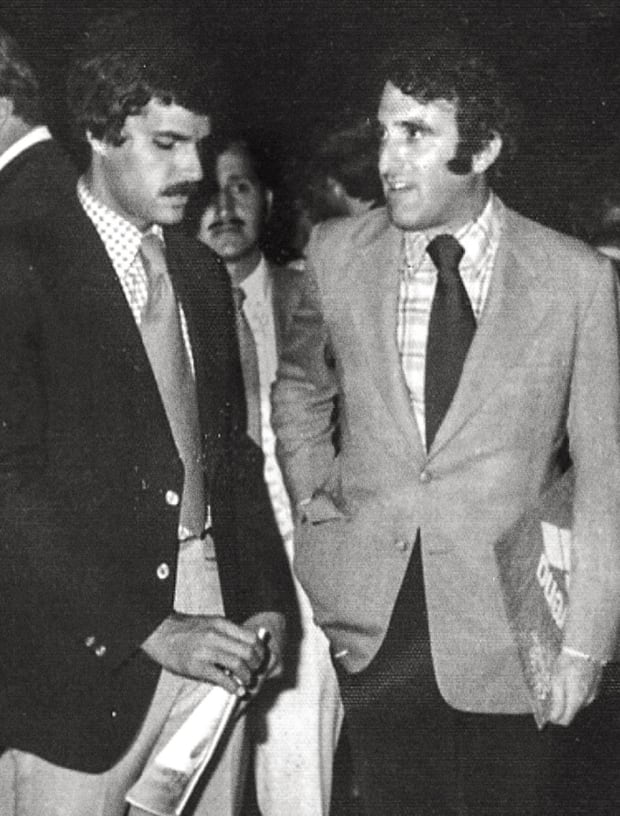

Courtesy of Jerry Kirshenbaum

It was obvious that the United States Olympic Committee’s media people hadn’t alerted Spitz to the assault at the Olympic Village, allowing him to arrive at the Press Center unaware. The USOC wasn’t known for its competence. In The 50-Meter Jungle, his memoir about training Spitz and other Olympic champions, Chavoor indicts the USOC for a worse transgression. He writes that USOC officials had met with Spitz and the coaches at 8:30 that morning “to discuss the press conference, and it was business as usual.” Astonishingly, according to Chavoor, “they knew but no one said a word to us about the tragedy that was taking place at the time.”

I sought to put Spitz’s mind at ease. I told him that what the assembled media, myself included, now most wanted was a briefing from authorities about the horrific events unfolding in the Olympic Village. I said I thought that the press conference with him would be put on hold.

I was wrong. A Press Center official approached, ready to escort Spitz to the stage. He would face the press after all. I said, “Mark, you do know that they’re not going to be as interested in the swimming. They’re going to ask you about what’s happening with the Israelis.”

“What should I say?”

“Just say what you feel,” I said. “But I don’t think you should say, ‘no comment.’”

That last part just came out.

The first question to him was indeed about his reaction to the assault against the Israeli athletes and coaches. “I think it’s awful …” he began, adding, in a panic, “no comment.” He slunk back from the microphone, wearing a stricken look. Other questions followed, but reporters yelled that they had trouble hearing his answers. Spitz’s appearance before the world press was a shambles. He hadn’t handled himself well, but the blame, I thought, had to be shared by USOC and Press Center officialdom.

Spitz was ushered off the stage. Outside the Press Center, a USOC van was waiting to take him to a pre-scheduled interview with German television. I opportunistically decided to skip the rest of the press conference and remain with Spitz in the hope of using my closeness to him more nakedly. I believed that being with him might get me into the Olympic Village, where the story now was. The Village was on lockdown, closed to the press and other outsiders, coverage of the hostage standoff largely confined to images captured by the long lenses of the ABC-TV cameras showing masked gunmen in tracksuits communicating with police crisis negotiators. I motioned to Anita to come with me. Together, at Spitz’s side, we would, I hoped, make it into the Village.

The German TV interview went off without a hitch. From the TV studio, the USOC van took us to the Olympic Village, which was ringed with police. At the entrance gate, a guard boarded the van. He studied Spitz’s credential, looked at his face, then checked the credential again. Finally, he said, “You go in.” Spitz may have been the most recognizable figure in all of Munich, but the guard was taking no chances.

Now it was my turn. The guard took one look at my press credential and commanded, “Out.”

I heard the familiar words, “It’s O.K., he’s with me,” but the Spitz magic no longer worked. The guard repeated, more urgently, “Out.” He ordered Anita off the van as well. As she and I were exiting, Mark asked me to meet him later at the hotel where his parents were staying. Standing together on the pavement, Anita and I watched the van pass through the gate and disappear inside the Olympic Village.

It wasn’t just the Munich Olympics that had starkly changed. Never would security at any future Olympic Games be as lax as it had been in the early days here.

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

Lenore Spitz, Mark’s mother, wasn’t in the hotel room when I got there, but Arnold and Mark were. There was a lot going on. Mark had been planning to stay on in Munich for a couple of days after the swimming was over, but because of the terrorist attack, Olympic and U.S. officials had decided it would be best for him to leave that very day. Arrangements were being made for him to fly home to California by way of London. Chavoor was to go with him.

The phone in the hotel room was constantly ringing. Once, Arnold answered and told Mark it was a reporter for the Associated Press. The reporter had tracked him down and wanted a statement from him about the assault on the Israelis. Arnold bellowed, “Why the hell are they asking Mark about it? It wasn’t his fault.”

“Arnold,” I said. “Nobody is saying it’s Mark’s fault.”

Mark ignored his father. He knew he should talk to the Associated Press. He asked me to help him prepare a statement. I once more inched across the line, but the words that went out over the AP wire were mostly his: “As a human being and as a Jew, I am shocked and saddened by the outrageous act in the Olympic Village.”

A few hours later, Spitz and Chavoor landed in London. As I would later learn, before proceeding on to the U.S., Mark posed in London for a photographer for the German magazine Stern for the iconic poster of him, hands on hips, in his star-spangled U.S. swimsuit, his seven gold medals hanging from his neck.

Following a one-day suspension of Olympic competition and a memorial ceremony in the Olympic Stadium for the slain Israelis, the Games resumed. I wrote Sports Illustrated’s story about the tragedy, titled, “A Sanctuary Violated.”

As the upended Olympics dragged dispiritedly toward their conclusion, during a free moment, I asked a German driver the magazine had been using, an obliging man named Hans probably in his late 20s, to take me somewhere, anywhere, away from Munich. Hans spoke no English, and my German was extremely limited. He and I ate bratwurst and drank beer in a beerhalle in a wooded area near the Bavarian border with Austria. It was the breather from the damaged Games that I needed.

After the closing ceremonies, I walked through the Olympic Village. Athletes were packing to go home, and the Village was emptying out. Outside the Israeli quarters at 31 Connollystrasse, a newly famous address, there were notes of sympathy posted on a wall expressing condolences in various languages, and wilting flowers were on the ground. Next to the front door was a discarded stack of the Israeli team’s press guides. I took one of them. It contained photos of the team’s athletes and coaches. A few of the pictured Israelis were smiling, but most wore determined, bring-on-the-Games expressions. I brought the press guide home and placed it in a plastic bin labeled “collectibles.” I’ve thought many times that I should change that to something else.

On May 16, 1973, eight months after Munich, Spitz married Suzy Weiner, a former UCLA student and sometime model he had been fixed up with shortly after his return home from the Games. Sports Illustrated’s editors saw the marriage as a good time to do a cover story on the ways Spitz’s life had changed since the Olympics. Heinz Kluetmeier and I were reunited with Spitz in Los Angeles for the assignment. Heinz’s photograph of a beaming Mark and Suzy Spitz graced the magazine’s cover. My story, “On Your Mark, Get Set, SELL,” recounted the business deals being negotiated on Mark’s behalf by William Morris superagent Norman Brokaw.

During our visit, Heinz and I joined the about-to-be-wed couple aboard Mark’s new 39-foot schooner, Sumark 7. Mark was excited that some of his Indiana teammates were coming to the wedding. “I wonder what they’ll think of my boat,” he chuckled expectantly. He said he was sure they’d be impressed by Suzy. Heinz and I agreed.

Mark and Suzy have been married 49 years and have two sons. Mark reportedly has done well in real estate. I haven’t seen him in ages. In the first years after Munich, I crossed paths with him at major swim competitions, where he was working as an ABC-TV analyst. He and I also spoke several times by phone. Once I asked him what he was up to. He said he’d been giving speeches at sports banquets and other gatherings. “I tell a few annydotes and if something in the news is bothering me, I give them a piece of my ear,” he said.

His occasional malaprops aside, Spitz did a good job for ABC, his commentary infused with insight and enthusiasm. In public appearances and in television interviews he has spoken feelingly about his experiences at Munich during the hours when the Mark Spitz Olympics morphed into the Terrorist Olympics.

In September 2007, my wife, Susan, and I vacationed in Germany. We visited Berlin and Munich, with a stopover in Würzburg, where we were shown the sights by a German-American friend who is a native of that beautiful city. In Munich, Susan and I had dinner at Käfer-Schänke, still one of the city’s most popular dining spots.

I mentioned to the maître d’ that being at the restaurant was nostalgic for me because I had gone there with Mark Spitz after he won his final gold medal at the 1972 Olympics. I wondered whether the maître d’ had heard about Spitz having had dinner at the restaurant that night. To my surprise, he told me that he had been present. He said he was then a young man working at Käfer-Schänke as a waiter. He remembered the occasion well.

“That was a wonderful night, wasn’t it?” he said.

I knew he was referring only to Spitz being there and not the carnage that followed, and I said yes.

More SI Daily Covers:

• Predicting Every Game of the 2022 NFL Season

• The Return of the Backyard Brawl

• Inside LeBron’s Grand Plan to Play With His Sons