He’s dabbled in yoga and massage therapy, herbology and psychology. The latest for the famed pot purveyor? Astrology, which he says ties it all together.

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

The line forms early outside of Elevate, a cannabis dispensary in Woodland Hills, Calif., that sells Alien Mints, infused lotions and bath bombs. But they’re not here—the grandmothers and bikers and hipsters crowding forward—simply to celebrate 4/20. They’re here, clutching water bottles stamped with marijuana leaves, holding footballs and Sharpies, to commemorate Christmas for the stoner set by meeting Ricky Williams.

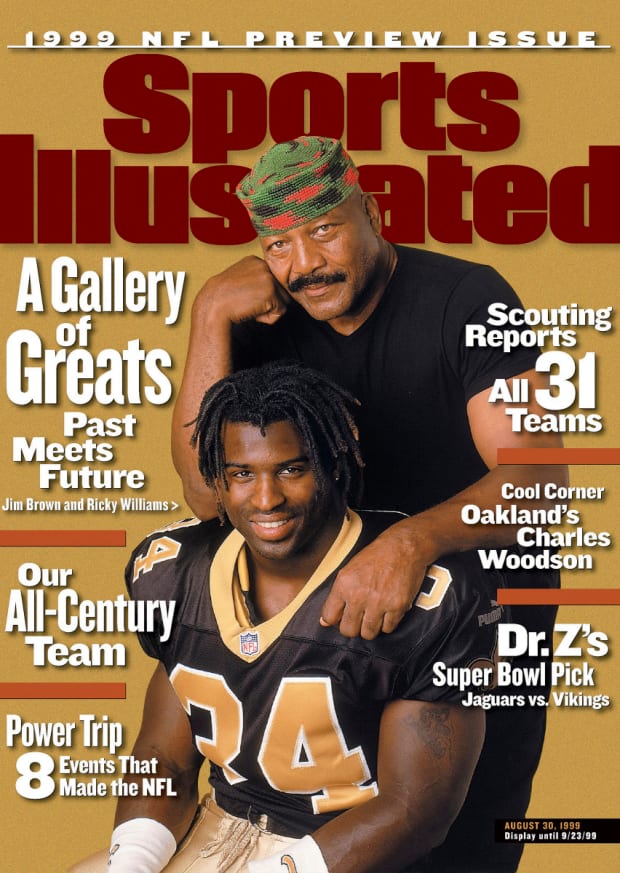

When their hemp hero finally walks up, heads snap like a hundred tennis umpires, everyone turning toward the man dressed in all black but for a tie-dyed facial covering. His dreadlocks, grown long, bounce atop the broad shoulders of a man who rushed for a shade more than 10,000 yards in the NFL. Williams waves shyly, then heads inside to a table set up in the back of the shop. But if these revelers are expecting some sort of gonzo experience, they don’t know Ricky Williams all that well.

He wants to dive deep, below surface connections. Beyond this whole We all love weed! vibe. Which is how he ends up at one point giving an unprompted discourse on mythology that speaks to how he landed at a business partner’s dispensary for a preview launch of his new cannabis brand, Highsman. This is classic “Ricky,” the catch-all term friends use to explain his erratic behavior, all the whims, all the metaphors and diversions.

In ancient mythology, Williams notes, the story arc rarely changes. The hero dies so that a young king can be born and grow wise. But in U.S. culture, specifically as it relates to professional sports, heroes aren’t supposed to age, let alone perish. “They’re meant to be young, vital and vibrant forever,” he says. “We don’t celebrate the wise king.”

In Williams’s head, that’s him, a king made wise by a lifetime of experiences. It’s not hard to find parallels to his story: the circuitous path for the sports star who famously walked away from football, pivoting into healing and philosophy while challenging social norms and the NFL status quo. His advocating for cannabis long before weed went mainstream, making him a hero to some—and a sort of alien to others, who mocked and meme’d him for potential unfilled.

Perhaps Williams, now 44, needed to die a death of public perception, needed to lose untold millions in NFL salary, in order to help create the more accepting world he lives in today. He certainly seems to see it that way. On a pothead holiday once celebrated in the shadows, he now hawks cannabis to the masses who came to find enlightenment, just like him. And today he wants to empower those masses, steer them toward finding their own inner Ricky, more or less. Show each of them that it’s O.K., preferable even, to become not who you’re expected to be but who you want to be. Who you are.

Later, Williams heads out into the sunshine and cars zip by on Route 101, past the billboard that screams FED UP WITH DRUG PRICES?, past the silver 4-2-0 balloons, right through that unmistakable aroma of pungent, earthy, dank. The fans, the balloons—Williams pays it all little attention. He’s intent on pushing forward the only way he knows: his.

Over the past five years—in the time, roughly, since Sports Illustrated last spent significant minutes with the 1998 Heisman Trophy winner—Williams has moved from Austin here to Los Angeles; divorced and remarried; welcomed his fifth child, a boy named Sol; and inked a podcast deal. Americans have, in roughly that same span, embraced the broad legalization of weed—and Williams, Mr. Weed himself, has shifted his focus elsewhere, evolving, Ricky-style, in unexpected directions. Cannabis remains a part of his vision, but he has a new obsession, and it’s at the core of his plans. It helps explain his past, and it points toward a bountiful future.

Says Ricky Williams, now a licensed astrologer: “Everyone is living a story. It’s just how they make it.”

Astrology, as Ricky Williams has come to understand it, explains not only his entire life but everyone’s existence. That’s heavy stuff, but it’s also, for him, on brand. He understands the skepticism from those who might not take him or his new interest seriously, but he’s not looking to convince or convert anyone, either.

This is what he believes: We’re each born on a specific day, at a specific time, and those data points—the alignment at that moment of celestial bodies, like planets and stars—give us, essentially, a rough outline of the life we’ll live. This does not mean that our fates are entirely predestined. Rather, the choices we make in living inform whether we eventually reach our lowest or highest potential—or, like most everyone, fall somewhere in between. We’re each given the template for our life. We fill in the rest.

The admirers who lined up to see Williams on April 20—from the dude in the Looney Tunes jacket to the woman with red dreadlocks to a staggering number of patrons sporting man-bun-and-tank-top combos—have each been given, like Williams, a blueprint. They chose on this day to come to his store, to connect through him with something greater. Most, it seems, expect quick interactions. They’re looking for a photo, a story, a hug. And they came to the right place. Williams obliges.

They’ve come to the wrong place, though, too. Because Williams also wants more from them. As he dishes out fist bumps and pens autographs and gifts eighths of marijuana, strangers shift the conversation toward golf and NFL highlights and the Hibachi Pappi food truck out front. But Williams, as much as possible, turns every loose mind-of-a-stoner thread back toward astrology. He’s probing, asking about their lives and their signs. He doesn’t give off that fleeting-celebrity-interaction vibe, where every communication begins with a shot clock nearing zero. He’s an active listener and an avid questioner, genuinely curious.

Williams lives what he expects from others. He’s open, detailing his own story, how it changed, and how that changed him. His path into his latest obsession began on his break from the NFL, in 2004, when he visited an ashram in Northern California. After a meditation class, the director, Swami Sita, sidled up to Williams at brunch and asked, “Where’s your Mars?”

He didn’t know how to answer that, because, well, how would anyone? But he followed Swami Sita into her office anyway and learned the basics about how his astrology chart related to his life, based on her trained interpretation. “It was the first morsel of clarity I had in months,” he says.

Williams didn’t quite dive headfirst into astrology back then. He dabbled instead in other pursuits, searching all along for something that tied together so many disparate interests. But around 2016 he says he again felt a celestial calling, particularly to the idea that his parents, his upbringing and the messages he consumed over the years had pushed him away from his true, pure self. He simply needed to untangle the “knots”—his word—that had been tied inside him by everyone and everything else. Astrology, he says, gave him clarity and enlightenment, the ability to understand his own actions. Within the context of his chart, all information felt like “breaths of fresh air” that unraveled those knots. This process, he says, “became fascinating, enchanting, almost addicting.”

Such enlightenment will come to everyone, Williams claims, if they’d just follow the wisdom of their own chart. If they’d understand that they’re living in a movie, and that they can adjust the script. When Williams adopted that mindset, he says, he stopped seeing himself as a victim. Others would come to believe that the NFL had wronged him, by forcing him to choose between a now-acceptable means of pain relief from his injuries and, essentially, a lucrative career. But he no longer saw it that way. Always against the grain. His chart showed that he would encounter turbulence, and navigate it.

What happened was supposed to happen, with variance built in for choice.

He thought back to something his mom used to tell him: “You didn’t come with an instruction manual.”

Now, he would respond, “Well, actually I did.”

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

At least that’s what he came to believe when he signed up for astrology classes, chose a mentor, Steven Forrest, and asked for private readings, along with his second wife, Linnea Miron. (A corporate lawyer, Miron now helps him run their company, Real Wellness.) Forrest stoked Williams’s desire to explore deeper, helping the lifelong healer become a certified evolutionary astrologer. At Forrest’s home Williams went through eight sessions of training, four days each, plus a “master class,” reading strangers’ charts while Forrest gave feedback and critique.

Williams, all the while, was still seeking, searching, feeling his own way forward. For most of his life he’d told himself that he wasn’t trustworthy when it came to relationships, that he couldn’t commit. He tended to delay meetings, miss phone calls or leave behind family and projects to fly all over the world at a moment’s notice, damaging relationships along the way. Williams acted the way he did, in part, he thinks, because he saw himself that way. Ricky. But Forrest told him that his chart showed decades of restlessness, an extended search for purpose; now he was entering a period of maturity and growth. And Miron’s chart showed a close alignment with responsibility. Put together, Williams deciphered that he’d met the right person, at the right time, to seize the right moment.

If this all sounds convenient—a way to excuse his worst transgressions and make random events seem part of some celestial order—Williams says he can only speak from his own experience. His chart, he says, helped him put past events in context and showed him what he’s meant to be doing now.

“It’s not about having the right answers,” he says. “It’s about living my truth.”

In 2017, Williams completed his astrology courses, earned his license and started deploying the medium, for those who believe in it, to give his clients a clearer picture of who they are, before anyone ever told them what to be. (That picture isn’t free. A 90-minute “Introduction to your chart” session with Williams—a “conversation,” he prefers to call it, not a reading—costs $300. An hour of “Astrological tutoring” runs $150.)

Williams’s own chart, though, remains the center of his universe, the baseline moving forward. Around the time that he hung his astrologer’s license up on the wall he began to look back at the most important moments in his personal history—like the day he retired from pro football for the first time, after just his fifth season. He wanted to see if his interpretations of his chart helped explain why he felt so compelled to do certain things that other people found to be extreme or weird, like waving goodbye to millions of dollars and moving to Australia.

He looked at July 18, 2004, and interpreted what he saw: On that date his sign, Gemini (suggesting an endless curiosity), was in close proximity to Jupiter, the planet of expansion, or adventure. Jupiter was in what astrologers call “the first house,” representing a new cycle, or new beginning, often associated with travel. Uranus, too, aligned strongly with Jupiter, a signal to Williams that on that day he’d needed to activate something inside himself and “stop pretending that I’m something I’m not.” He looked back, and in the stars he saw the beginning of a spiritual quest, illuminating a pull he says he always felt but could never voice all those years ago. He sighs thinking about it now. “The astrological symbolism,” he says, “is right on.”

That symbolism wouldn’t have mattered, though, had Williams not followed his instincts and left the game he loved. That part was his choosing, not predetermined. Had he stayed in football, he believes he would have limited his future. He thinks he’d probably be a coach today. “The individuation I found in astrology, yoga and spirituality really set the stage for the things I’m coming into,” he says. “That’s the universe giving us an opportunity to become more of ourselves.”

Astrology came to serve as a dot connector—a way to look back and make straight a meandering path. The football, the interest in photography and the appearance on The Celebrity Apprentice. The yoga, Ayurveda, massage therapy, herbology and psychology … Williams sees all these pursuits as tethered to what his chart had in store for him. Sometimes he made choices that maximized what was possible. Sometimes he did not.

Williams believes he’s wiser now, and he knows he came to that wisdom by the scenic route. He cackles at a question about regrets. Is there anything you’d do differently? “Yes!” he shouts. “Hell yes!” And, “So many things!” He would have shifted into other interests sooner, and listened less to team doctors who pushed opioids on him and coaches who preached conformity.

More than anything, though, he says he would have paid attention to the stars. If he had, he would have noted that his chart painted him as a “healer”—something he always felt in his soul. He believes he left football instinctually, to find himself, because he knew that sports would never fully define him. He notes that his “south node”—in astrology, an indication of one’s past—is Ares, suggesting that in a previous life he was a warrior of some sort. And football, he says, fulfilled that part of him, helped him master his past. Indeed, he needed the game, just not as much as most people believed he needed it.

Williams says he first began to stray from conventions during his senior year at Texas, after he broke up with his girlfriend, who then started dating one of the Longhorns’ quarterbacks—a teammate he knew well. His roommate at the time suggested he smoke some weed. He did, and a calm washed over him. “I wouldn’t have won the Heisman without it,” he says.

Later he would look back and see those moments as his first glimpse into meditation. It calmed him, made him more reflective, more introspective, even a better player, he says, as he spent more time thinking about how to improve. After his roommate handed him that first bong, he ripped off a series of 200-yard rushing games.

Introspection, though, stoked social anxiety, which the Saints exacerbated by trading a bounty of picks to draft him at No. 5 in 1998. Near the end of a bumpy, injury-filled rookie season, coach Mike Ditka summoned Williams for a meeting. “They love you—they just don’t understand you,” Ditka told the running back of his teammates, even though both men knew he was “Ricky Weirdo” to most. Williams believes Ditka considered him aloof, but not in a bad way; the coach just wanted Williams to let his teammates in. But in the masculine, less-than-evolved world of pro football, Williams says he didn’t feel safe showing his true self.

The stoner-outcast portion of his story—the 500-plus cups he says he peed into for drug tests, the two league suspensions, the yearlong sabbatical he embarked upon—can now seem out of some distant past. In hindsight, the NFL’s harsh treatment of Williams feels uninformed, misguided or draconian, depending on how one views the evolution of cannabis reform. But don’t mistake that to mean that he’s sitting around, waiting for an apology. It was never the point to prove wrong people whom he knew to be wrong. The point was to find his purpose, his way. To evolve. Strangers—people who hadn’t lived his life, who didn’t understand him—wanted money and celebrity to fulfill him. But all those things just made him anxious, like he didn’t belong or wasn’t worthy or hadn’t been let in on the secret to a happy life.

Williams believes he would be in the Hall of Fame had pro sports in his time been more accepting, more understanding, closer to what they are today, inching toward enlightenment. But he rejects the notion that he should have sought only money and celebrity. To him, a bust in Canton without the rest of what he calls “my path” would have been an unfulfilled life. He says he would have “hated myself.”

The more he has studied his own past, the more astrology has explained Ricky to Ricky, the more his future has crystallized, he says. Making sense of what happened made clear what should happen next. “The universe is challenging me now to do something with all this” information, he says.

At the weed-apalooza in L.A., Williams confesses: This April is the first time he celebrated. He’d imbibe in the past, of course, but not for the holiday specifically. “I guess I didn’t get it,” he says. “For me, every day is 4/20.”

That he’s now embracing it speaks to where his astrological chart pointed him, toward a “midlife opportunity.” Chatting with one fan who goes deep on cold-water-immersion therapy, Williams discovers they’re close in age and tells the man that most people, if they’ve sought wisdom and applied it, peak after 40. Sometimes long after. “Serendipity is everywhere,” he says, “as long as you’re open to it.”

Enter Highsman, his cannabis business. If weed helped Williams win college football’s most coveted trophy 23 years ago, and if weed contributed to his football downfall, then weed can help him make back what he lost.

For now, his offerings include three strains, each expected to sell for $45 per eighth-ounce, each built to attain a certain high. The lemon-flavored Pre-Game is a sativa, grown to stimulate; Post-Game, a berry-flavored indica, induces relaxation; and Halftime is a hybrid of the two. The varieties even come packaged in team colors tied to Williams’s career: burnt orange for Texas, black-and-gold for the Saints, and that obnoxious Dolphins teal.

If that sounds like he has sold out, consider: Maybe the world has just evolved to his thinking. The NFL and other leagues have relaxed long-held stances on marijuana. Sixteen states have legalized cannabis; 37 now permit use for medical purposes. Meanwhile, Williams, who played a role in that sea change, has evolved, too. His life isn’t defined by weed anymore. And his chart, he says, indicated that he would harness his business acumen right at the midlife opportunity point. In other words, now.

It might seem like an unexpected turn, the infamous pothead becoming an entrepreneur, settling into a CEO role, with endless discussions about price points, distribution and branding, all leading up to a full rollout of the Highsman product right before football season. Even Williams admits he initially balked at the idea of going full-fledged capitalist. “My whole life, I’ve had an internal resistance to that space,” he says. Sure, he made millions playing football, but he was still a laborer—the talent, not the boss.

In recent years, he unwound that particular knot in therapy, plunging into conversations about manhood and toxic masculinity, exploring how both concepts, he says, had limited him. As a business leader he started to draw on the leadership styles of past football coaches and mentors. Meaning: Of all people, Bill Parcells, who overlapped with Williams in Miami, influenced his commercial turn.

His therapist pointed out that by being compassionate, loving and in charge, he could, as Williams says, “bring more consciousness into the world.” They settled on a term he loves: the conscientious CEO.

Inside the dispensary, Williams sits at a table in the back, Sharpie in hand, samples of Highsman stuffed in the bag at his feet. Someone mentions the George Floyd murder case—the jury has just returned a guilty verdict against officer Derek Chauvin—and cellphones light up with news alerts. Williams smiles. Something about the world, the direction he’s headed, the fight against social injustice, just feels right.

“That’s great,” he says. “That would have put people in a tough spot. I mean, it’s 4/20. … It’s smoking season, baby! We’re talking about peace!”

Peace is an important concept to Williams these days. He found his own calm as the world descended into chaos and division. While COVID-19 shut down sports, closed borders and threw economies into recessions, he decided to expand his aims. And as he started to put everything together, he found something unexpected. Balance, more or less. Calm. Clarity. Just as his astrological chart had shown him.

The next afternoon Williams will drive from his home in Venice Beach to Van Nuys, where there’s a building near a golf course and strips of rundown houses, with no sign out front. This is where Elevate’s owners grow Highsman and other strains. The giveaway isn’t the unmarked door but the unmistakable smell that wafts halfway down the block. Williams will be greeted there by his Highsman partner, Matt Cohen, and Elevate’s Kevin Krivitsky. They’ll head inside for a tour, passing through grow rooms full of Biscotti and Krypto Kush blends, then into drying rooms, pausing for smell tests. They won’t smoke weed here, only discuss how to market their cannabis product, and how to align it with Williams’s now grander aspirations.

Williams has dreamt big before, only for plans to fall through, business ideas to bomb at the planning stage, scorned partners to split. Whether he’s more serious now is less important than this: He’s better equipped, he says.

He points out that Sol was born on June 1 at 9:21 p.m., or 21:21, which is significant. For one, they’re both Geminis, father and son. Also: The time of birth was later than expected, requiring a C-section; Sol arrived at the exact time that the rising Capricorn sun hits zero degrees, right when the days are starting to get longer, indicating a bountiful life. Or something.

In his own future Williams can see himself chairing a university department—something like the Ricky Williams School of Cannabis, maybe at the University of Texas. He can envision running wellness centers that feature all of his favorite types of healing, plus cannabis, plus astrology. Ultimately, he’d like to open an ashram, the same kind of facility where astrology first called to him. Then, he says, he’ll become the Michael Jordan of sports wellness.

He says he has never been happier. That contentment derives from relationships new and old. From all of the clients who tell him he changed their lives. From all the strangers who reach out to him, thanking the infamous stoner for the path he blazed. From the onset, again, of fatherhood—and from, he says, being more prepared for it this time. From a rekindled connection with his mother, who endured so many jokes and criticisms pointed at her son, who didn’t understand his relationship with marijuana until she dealt with her own health problems in recent years. The two smoked weed at a relative’s house on Thanksgiving, mother and son, leading not to an apology but recognition, understanding, healing.

“To a certain extent, I feel sorry for people who are so close-minded,” Williams says of those who shamed him over the years. “I guarantee they’re suffering more than I am.”

It’s difficult to fully square this latest iteration of Ricky Williams with all the previous versions—football star, pariah, journeyman, healer, cannabis researcher. … Maybe he’ll change his mind again, or five more times, pivoting into something new. Chances are, he’ll be ahead of his skeptics, ahead of perceptions, and he won’t care one bit.

There’s a Bob Marley lyric he likes, from the song “Corner Stone,” that speaks to all of this—his life now, everything changing rapidly once again. The stone that the builder refuse will always be the head cornerstone. (It’s actually a Bible verse, but why quibble?)

On 4/20, Williams begins walking down Ventura Boulevard. He has been rabbit-holing on astrology, charting stars, getting deep with strangers and handing out weed samples for hours. So it’s only fitting that he strikes up a conversation with a stoner whose T-shirt is stamped IT MUST BE 4.20 SOMEWHERE. This man—young and fit, his Dodgers cap turned backward—doesn’t know who Ricky is. But Williams doesn’t feel the need to enlighten him on this particular point. Not exactly.

“What’s your name?” the man eventually asks.

“Ricky,” he says. “I was a football player. And then I wasn’t. And that became part of my story.” He pauses, as if reflecting, looking back.

“Everything is different now,” he says.

More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• The Charmed Season: Revisiting Derek Jeter’s Origin Story

• We Could Sure Use Dick Cavett Right Now

• Pete Sampras Is Doing Just Fine