It has to do with tanks in Shenzhen, mariachi bands in Guadalajara and a legacy passed down by players for 50 years.

Steve Simon didn’t start the year expecting to be in central Mexico in mid-November. But COVID-19 has made improvisers of us all, including the CEO of the WTA Tour. He anticipated closing out the 2021 season in Shenzhen, China, at the WTA Finals, the event from which the Women’s Tennis Association derives a significant share of its revenue. Just three years earlier, to much fanfare, he’d signed a deal to hold the Finals there for the next decade, doubling the tournament’s prize money purse to $14 million. But when the event was canceled in July for the second straight year on account of COVID-19, Simon resembled a tennis player caught out of position and was left scrambling.

At one point in late summer, there were discussions about holding the year-end event in L.A., in conjunction with the release of King Richard, the Will Smith star vehicle that lionized Richard Williams, father of Venus and Serena. When that fell through, an unlikely substitute host emerged: Guadalajara. This wasn’t a city that had ever figured prominently on the tennis circuit. The organizers could put up only $5 million in prize money, roughly one-third of the Shenzhen haul. And the date on the calendar couldn’t move, so an entire year-end lollapalooza had to come together in a matter of weeks.

But come Nov. 10, the WTA caravan converged on the Panamerican Tennis Center in Zapopan, Mexico, and one of the great tennis stories ensued. Starting on the first night, an unmistakable energy pulsed through the stadium. While the inaugural Shenzhen event in 2019 was marked by oceans of empty seats, in Mexico, the stands were packed. (So much so that by the third night, Guadalajara had already drawn more fans than the entire week-long Shenzhen tournament.) Mariachi bands performed. The weather cooperated. Player after player gushed about the ambiance and hospitality.

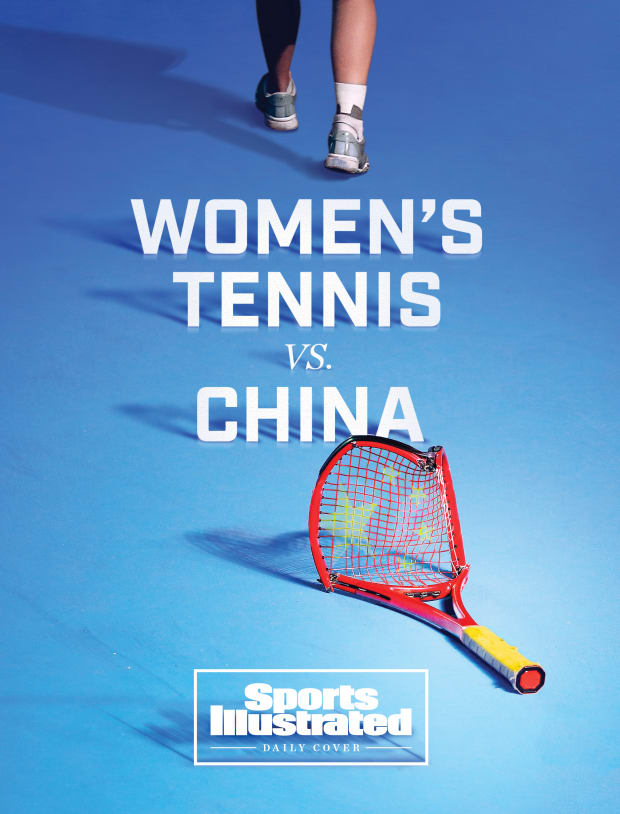

Photo Illustration by Dan Larkin; Hector Vivas/LatinContent/Getty Images (racquet); Alex Grimm/Bongarts/Getty Images (tennis shoes)

But these good vibes were offset by a diplomatic crisis emanating from the country originally slated—and now apparently destined—to be the focus of the tennis world that week. When Simon wasn’t watching the matches, he was on his phone or running through a gauntlet of meetings both at the tournament venue and at the tournament hotel, the Guadalajara Hilton. At breakfast, in meetings with the WTA Board, interacting with WTA royalty such as Billie Jean King, Martina Navratilova and Chris Evert, who had come for the festivities as honorary guests, the same fundamental questions surfaced: Where was Peng Shuai? And what was the WTA going to do about the 35-year-old veteran player, marooned in China, her health and her whereabouts uncertain?

Simon’s answer would plunge the WTA into direct conflict with a global superpower—the very one that figured so prominently in its finances and future growth plans. A source tells Sports Illustrated that more than one-third of the WTA’s roughly $100 annual million in revenue comes from its dealings in China. Simon’s response would also—one way or another—send a message to the global sports community, starting with his own players.

By putting, as he phrased it, “principles ahead of profit,” Simon and the Women’s Tennis Association decided to do what the NBA, Nike, Microsoft, Starbucks, Blackstone, Goldman Sachs and innumerable other global businesses vastly greater in size, power and revenue have not.

How was it that the WTA stood up to China’s authoritarian regime? It owes to a swirl of factors, figures and fortune—all rooted in the specific history and legacy authored by the WTA’s players over the last five decades.

Fred Lee/Getty Images

Years in advance of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, China made a massive national investment in sports. And in the early 2000s, it was starting to bear fruit. Around the same time that Yao Ming entered the NBA to great fanfare, going as the first pick in the ’02 draft, China was minting its first two stars in women’s tennis. Li Na was a limber athlete, an alloy of speed and power. The other prospect, Peng Shuai, was comparably talented, but her potential was complicated by her willingness to confront authority, particularly the state-run Chinese tennis system.

A prominent sports consultant in China put it to me this way more than 15 years ago: “[Peng] caused a bit of a stir last winter by effectively resigning from the Chinese Tennis Association. Peng was upset with the way the CTA was dictating her playing schedule and telling her what tournaments she could play and assigning her coaches without her input. In the West, it would be normal for the athlete to just walk away from the federation but in China, a very rare situation. But the CTA backed away after some very ugly PR moves backfired.”

Peng was 19 at the time.

Li Na would go on to win the French Open and the Australian Open, and in 2019 was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame. Peng Shuai had an accomplished career as well, establishing herself as a credible singles player, once reaching the semifinals of the U.S. Open. She also became a standout doubles player, reaching No. 1 in the rankings, winning Grand Slam titles including Wimbledon, and representing China at three Olympics.

As significant as her accomplishments are, though, she will be most known for the news she made off-court this fall. On Nov. 2, she posted on Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter, what was essentially an intimate first-person essay about feeling spurned and being a survivor of sexual assault. Her account was rich in detail and specificity, as she accused Zhang Gaoli, a former vice premier in the Chinese Communist Party, of carrying on a years-long affair with her, before forcing her into nonconsensual sex. Her account was also rich in length—more than 1,600 words—and in literary flourish, as she compared the power imbalance to “hitting a rock with an egg, or being a moth that flies towards the flame.”

This was believed to be the first public #MeToo allegation leveled against a public figure in China, never mind a high-up in the CCP. In a country that spends more on internal surveillance than on its military—a suggestion that it perceives its biggest threat to stability and unity as coming from within—this did not go over well.

Since his rise to power in 2012, Chinese president Xi Jinping has moved aggressively to squelch dissent, both in the streets and online. The world was now getting another vivid glimpse of what Chinese censorship looks like. It took barely 20 minutes for Peng’s account to be scrubbed from the internet. Zhou Fengsuo, a Chinese human rights activist and former student leader during the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, now exiled and living in U.S., says that one of the most sinister parts of life in China is knowing that the sword of censorship hangs over you. “There’s no clear line,” he says. “You live with this ambiguity: Is what I am saying—or thinking—O.K.? If not, it disappears.” One China expert, though, told SI that Peng’s essay was so full of terms and names that should have triggered the censoring algorithms, the real question is: How did it stay up for 20 minutes?

Peng followed her explosive, achingly emotional allegation with … nothing. No more posts. No interviews. No public appearances. Within days, #WhereIsPengShuai became a hashtag worldwide. Except in China. When the search term “Peng Shuai”—then simply “tennis”—was entered into Baidu, the Chinese equivalent of Google, it yielded no reference to Peng or a story that was making worldwide news.

Lintao Zhang/Getty Images

It’s easy to lapse into cliché and sentimentality, but there’s a sisterhood and lineage on the WTA Tour. Old players mentor younger players. Younger players pay homage to their forebears. This transacts in person and also on social media, where King and Navratilova and Evert will retweet teenagers. And vice versa. “It’s always been this way,” says Pam Shriver, a former player and current broadcaster for ESPN and Tennis Channel. “There’s a real sense of family.”

There’s also a real sense of activism and mission that goes beyond hitting yellow balls. Founded almost 50 years ago as a breakaway tour, separate from the men, where women could control their own destiny and finances, the WTA has always nodded to social justice. When the WTA’s founding members, the so-called Original Nine, were inducted into the Hall of Fame last July, the ceremony came drizzled with terms such as “trailblazers” and “moral courage.” That’s extended to today when, say, a player like Naomi Osaka generates as much attention for her stance on Black Lives Matter or mental health awareness as for her four major singles titles.

Suddenly, in November, Peng Shuai, a stalwart, a member of the sisterhood, was not only making a #MeToo allegation but was being censored by an authoritarian country. And then her whereabouts became unknown, as colleagues’ attempts to reach her proved unsuccessful. Looked at one way: Had the WTA community sat silently, it would have undercut credibility and undermined activist sentiment going forward. More charitably, the spirit and culture instilled by King, Navratilova and others would come to bear and China would feel the full force of the WTA’s collective voice, starting on social media.

Alizé Cornet, a French veteran, was among the first who expressed concern on social media over Peng Shuai’s situation. Dozens of other players followed. And then the former players—starting with King, Navratilova and Evert—weighed in, posting multiple times a day. Osaka appealed to her four million Twitter and Instagram followers, specifically referencing censorship, the great third rail when discussing China. Soon, #WhereIsPengShuai? was a trending hashtag.

All this stood in stark contrast to the minor crisis that occurred two autumns before, when Daryl Morey, then a Houston Rockets executive, issued a tweet expressing support for pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. China responded by banning the broadcast of NBA games. Faced with potentially even greater business losses, the league tiptoed around the situation with carefully crafted statements. LeBron James—who has significant business interests in China—scolded Morey. Other players and coaches, often outspoken, seemed to suddenly misplace their tongues.

In the WTA’s case, there was consensus. From players of all levels. From the alumnae. From their agents. From the WTA Board. Navratilova notes that for years it was axiomatic that there were “three T’s” that were considered taboo to the Chinese government: Tibet, Taiwan and Tiananmen. “Now, we can add a fourth: tennis.”

Matthew Stockman/Getty Images

Steve Simon, age 66, has been the CEO of the WTA since 2015, and you’d be hard-pressed to find both a more consummate tennis insider and a leader less inclined to grandstand. A former college tennis player at Long Beach State, Simon kicked around in tennis’s equivalent of the minor leagues—he once played a Wimbledon main draw match in mixed doubles—before taking a series of sales and sponsorship jobs in the sport. First with Adidas, then with the event held in Indian Wells, now owned by billionaire Larry Ellison, where Simon rose to become tournament director.

Measured and unassuming, Simon has always carried himself less like an ex-jock or slick salesperson than a cautious and thorough accountant. He began serving on the WTA Board of Directors in 2004, and colleagues say he was often the voice of reason in the room. “He’s introverted. I wouldn’t say he’s charismatic. And at the same time, he is such a strong communicator,” says Shriver, who praised the openness and transparency with which he’s piloted the tour through the pandemic.

In 2009, Larry Scott left the WTA CEO position to become commissioner of what was then the Pac-10 Conference. A board member encouraged Simon to take over. Simon demurred and suggested the WTA could use a female leader. He backed Stacey Allaster, who got the position. But when Allaster completed an unremarkable term, Simon replaced her in ’15.

Characterized by players like Victoria Azarenka as “more of a listener than a talker,” Simon was happy to let the players occupy the foreground and happy to let other WTA colleagues make the public appearances. One of his early accomplishments entailed brokering Serena and Venus Williams’s return to Indian Wells after an ugly, decades-long boycott prompted by treatment from the crowd that Serena has said had an “undercurrent of racism” that “was painful, confusing and unfair.” Simon took no victory lap. At the time, he turned down an interview on the matter, insisting this was the Williams sisters’ story to tell, not his.

Some of Simon’s close friends and colleagues say they don’t know his politics. The next person to describe him as ideological will be the first. There is, instead, a pragmatism and fidelity to the institution. “He’s one of those people,” says a former WTA Board member, “who has a knack for just looking at things calmly, clearly: I’ll analyze a problem and try to make the right choice. … He is a right-is-right and wrong-is-wrong guy.”

As CEO, Simon was tasked with putting the WTA on firmer financial footing. One of his great dilemmas: figuring out what to do about China. Under Allaster, the WTA had embarked on what it called its China Strategy. Catalyzed by the success of Li—and to a lesser extent Peng—China had taken a liking to tennis, and its government was willing to fund WTA events. Bidding against the largest government in the world, the private promoters that had been hosting tournaments were little match for the Chinese sports machine. Event after event migrated to China. Other tournaments were created from whole cloth and added to the WTA calendar. By the late 2010s—despite no longer producing top players—China hosted 11 WTA events, more than any other country in the world.

There was a central, inconvenient truth, an open secret: The players had little use for China. There was something unseemly about this nakedly transactional relationship. The events were often staged in arenas devoid of fans and in uncomfortable situations. One example: When Shenzhen held the WTA Finals event in 2019, players could see Chinese tanks positioned menacingly in the direction of adjacent Hong Kong. In the stadium parking lot, Chinese soldiers practiced riot drills, preparing to squelch pro-democracy protests.

Factor in the travel, time zone adjustment, language barrier, even the traffic, and it’s no surprise that players developed a habit of withdrawing from events in China just before a tournament’s start, often with dubious injuries. Consider: While China figured prominently in the WTA’s business model, Serena Williams hasn’t played an event in the country since 2014.

On the other hand, the money sloshing around China was undeniable. Despite the militarized setting, at that 2019 Shenzhen event, Ash Barty won the title and earned $4.4 million, the biggest purse ever conferred on a player—male or female—at one tournament. The Chinese events paid the WTA comely fees to sanction their tournaments. The Chinese events also paid millions in operating contracts to U.S.-based management firms, like Octagon and IMG, to promote and run the events. And brands such as Nike and Rolex were all too happy when the individual stars they sponsor played in a market with 1.4 billion potential consumers.

It was under Simon that the WTA signed its deal to hold its championships in Shenzhen. But, privately, multiple sources tell SI, he was never comfortable with the heavy reliance on one market and had long been looking to rebalance the portfolio. Multiple sources say the WTA’s financial concerns have intensified given that Gemdale, the company underwriting the Shenzhen tournament, is a property development firm operating amid China’s real estate debt crisis.

When, on account of COVID-19, the 2020 Chinese WTA events were canceled from the calendar, Simon could glimpse a world without China. Then, in the fall of ’21, amid a new crisis, he was really confronted with the prospect of the WTA leaving the country.

Matthew Stockman/Getty Images

To Simon, the WTA Board and the players, the success of Guadalajara was proof that the WTA Tour was nimble. In a matter of weeks, it could switch to an entirely new venue on an entirely new continent, and a successful event could materialize. The prospect of leaving China was suddenly looking less daunting.

With the clear backing of the tour’s players—past and present—on Nov. 13, Simon aired his grievances and frustration publicly. Expressing his inability to connect with Peng directly, he demanded that the Chinese officials conduct a “full, fair and transparent investigation” into her allegations. He also demanded proof of her safety. He added that if China was not in compliance, he would have to consider taking his business elsewhere.

To some, the salvo may have seemed naive. The notion that China—an autocracy with no free press and censors that block search terms—would capitulate and suddenly issue an investigation because a women’s tennis tour based in the U.S. made a demand, was optimistic at best. But to others, it read as strategic. As Shriver says, “You don’t make a threat you’re not willing to carry out.”

China returned serve, making no reference to any investigation or willingness to take seriously Peng’s allegations. Instead, through a state-run media outlet, it released a statement attributed to Peng.

Sounding nothing like the player writing on the 1,600-word cri de coeur—or the words of a player who, 15 years ago, was already known for confronting Chinese authority—it read in part: “Hello everyone this is Peng Shuai... I’m not missing, nor am I unsafe. I’ve just been resting at home and everything is fine. Thank you again for caring about me. If the WTA publishes any more news about me, please verify it with me, and release it with my consent. As a professional tennis player, I thank you for all your companionship and consideration.”

It also walked back the allegation of sexual assault.

Simon shared the skepticism of many and reiterated his demand for an open investigation and independent proof that Peng was safe. The Chinese government did not address this request but did make Peng available to the IOC for a video chat. With just three months until the Winter Olympics in Beijing, the organization had every reason to want a story about China’s oppression of an athlete to fade from the headlines and from social media. After the call, IOC president Thomas Bach expressed satisfaction that Peng was unharmed and acting on her own accord. Few were convinced.

Simon was among those who remained unsatisfied, and on Dec.1, he followed through with his threat. Two weeks had gone by without evidence that Peng was able to speak freely or that the demands for an investigation were taken seriously, and so he announced that the WTA was suspending tournaments in China indefinitely. “None of this is acceptable nor can it become acceptable. If powerful people can suppress the voices of women and sweep allegations of sexual assault under the rug, then the basis on which the WTA was founded—equality for women—would suffer an immense setback. I will not and cannot let that happen to the WTA and its players.”

The hypothetical had now become concrete. The WTA is out of China, at least for the foreseeable future. And—absent a considerable change in policy by China, or considerable capitulation by the WTA—this freeze isn’t thawing. And still, Simon has faced virtually no internal opposition. Says one top U.S. player, “Everybody is relieved to have it not be a choice.” Adds Shriver: “The discomfort of going, it’s been taken out of their hands.”

As Simon put it to me during an interview for Tennis Channel: “There’s been unanimous support for the direction and the approach. … More importantly, there’s [unanimous] deep concern for Peng Shuai and making sure she’s O.K.—and not just from a physical perspective.”

Prioritizing principle ahead of profit. Ceasing to do business with a country with values inconsistent to yours. Effectively standing up to a bully. … It sounds fundamental. But companies with far more leverage and far more revenue haven’t shown a fraction of this conviction.

The WTA, however, remains largely out on an island. In a repudiation of the WTA, the IOC said it preferred “quiet diplomacy” when dealing with China. Trying to save face a week after the video conference with Peng, it walked back its breezy assurances of her well-being. But it was all the typical IOC buffet of garbled statements, clumsy PR, and rank hypocrisy. The organization had shown itself to be a tool of Chinese autocracy. The Winter Games in Beijing will go on as planned.

It should be noted that Zhang Gaoli, the man that Peng says sexually assaulted her, was the face of China’s organizing efforts for those games.

For now, anyway, men’s tennis events will go on in China as well. ATP players have been supportive of their WTA counterparts. But the organization is a 50-50 partnership between players and tournaments. The tournament side–including a board member who runs the Shanghai event—has been cautious not to follow the path the WTA has blazed. Though it enraged a good many players who considered it a spineless response, the ATP issued a statement that essentially argued for a wait-and-see approach.

It remains to be seen to what extent NBC and other broadcasters address Peng Shuai during February’s Olympic coverage. It will be interesting to see what will happen when athletes interviewed in Beijing or on the medal stand will use the occasion to call attention to Peng specifically and China’s human rights abuses more generally. It will also be interesting to see whether and how Chinese events pursue action against the WTA for breach of contract.

Meanwhile, the most pressing question inside women’s tennis remains #WhereIsPengShuai? At this writing—more than six weeks after her initial post—she has not reengaged on social media, not reached out to Simon, nor to any player. (SI contacted the Chinese Embassy in Washington for comment but received no response.)

There is also the future of the tour. To maintain its growth, the WTA will need to alchemize all this goodwill and publicity into revenue—specifically the revenue it will lose by divesting from China. Sources tell SI that in recent weeks, Procter & Gamble has reached out to the WTA about potential new business. Simon is optimistic that other markets and host cities will surface to take over the Chinese sanctions. But seldom does a business self-exile from a market and jeopardize one-third of its revenue without a concrete backup plan. “This is not where we wanted to end up,” Simon told SI. “But here we are. Some things are more important than money.”

Zhou Fengsuo, the former Tiananmen Square student leader, now living in the U.S., has watched this unfold with a mix of concern and admiration: “We may not know for sure what is happening with Peng Shuai. With China you never know. But we know she is safer now than before because of the international attention. Because the WTA is standing so firm. That’s what makes her safe.”

• He Nearly Died on ‘Drive to Survive.’ Now He’s Faster Than Ever.

• Tom Brady Wins the 2021 Sports Illustrated Sportsperson of the Year

• Billie Jean King Wins SI’s Muhammad Ali Legacy Award