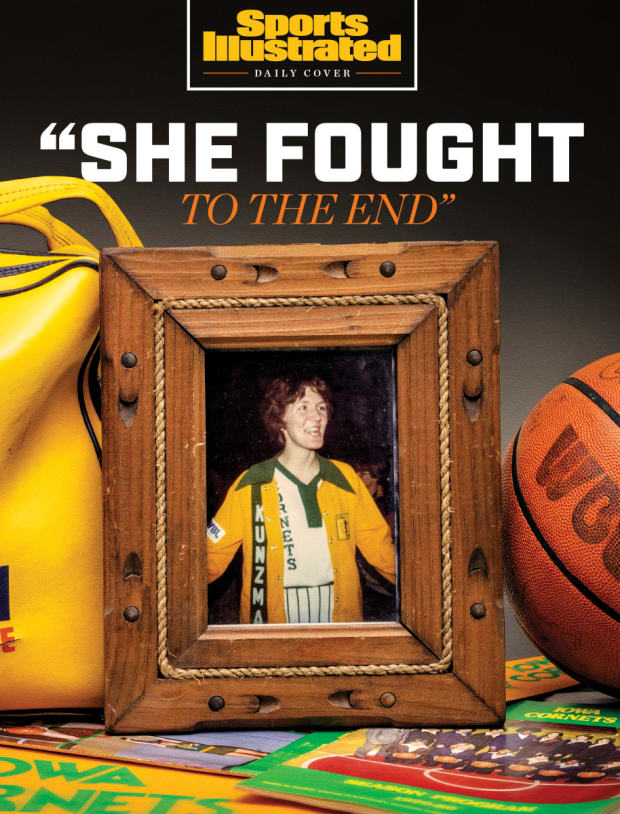

Long before the WNBA, there was the WBL. And there was Kunzmann, who scraped and hustled to relative fame in a shoestring, sexist league. You might know her name today, if not for a horrific act 40 years ago.

Two days before she was murdered, Connie Kunzmann played the game of her life.

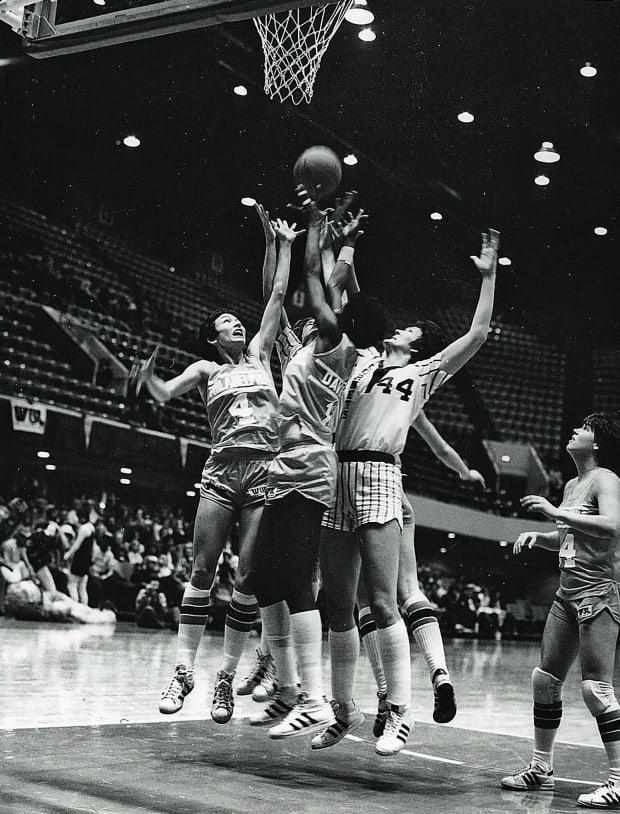

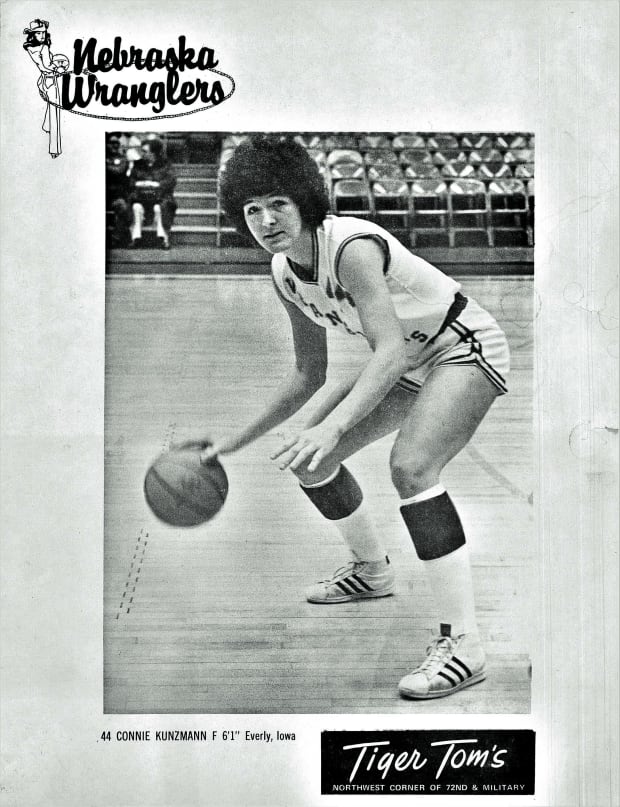

It was the evening of Feb. 5, 1981, and Connie, a long-limbed 24-year-old with a halo of curly brown hair, was matched up against the best women’s basketball player on the planet, Dallas Diamonds point guard Nancy Lieberman. The face of the nascent Women’s Professional Basketball League, Lieberman was as skilled a passer as she was a scorer. Kunzmann? She was a 6' 1" reserve forward for the Nebraska Wranglers known for her tenacity, defense and exuberance. If Lieberman was the WBL’s Magic Johnson, then Connie, as friend and one-time teammate Molly Bolin puts it, was “our Kurt Rambis.”

From the time she picked up a basketball, as a seventh-grader, Connie had devoted herself to the sport. A standout in high school and college, she’d jumped at the opportunity when invited to try out for the WBL, the first women’s pro league. The job wouldn’t pay much, but she didn’t care. She was all in.

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

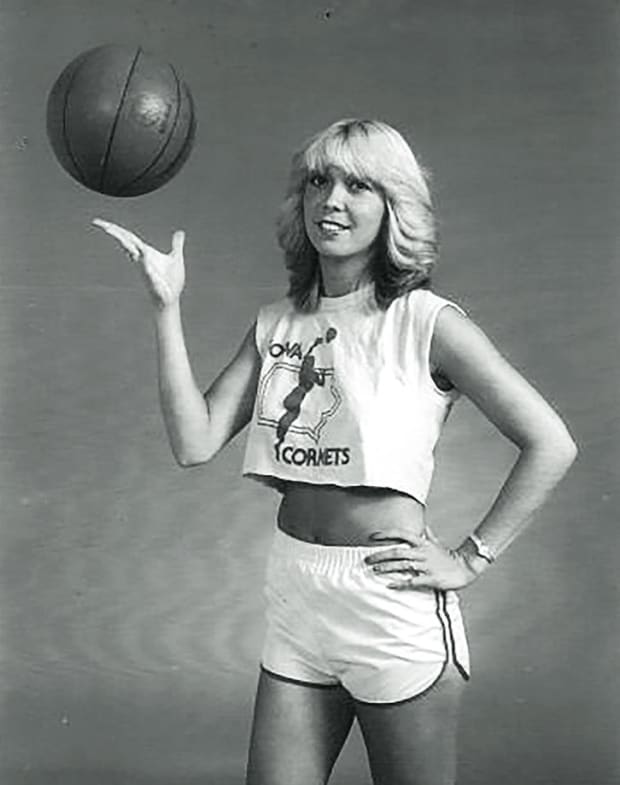

Since then, Kunzmann had been a key cog on the Iowa Cornets and then the Wranglers. She set a WBL single-game record with 11 steals, won her team’s Hustle Award and played in the league’s first two championship series—and she had a blast doing it, traveling coast to coast, goofing off in the back of the bus, seeing cities she’d only read about. But after a slow start to the season, Kunzmann found herself on the bench. Three days before the game against the Diamonds, Steve Kirk, the Wranglers’ humorless coach, told her he didn’t know whether she could cut it anymore. Play better, he reportedly told her, or you won’t travel with the team. Kirk’s words cut hard. Usually self-confident and extroverted, Connie began fretting and had fallen into dark moods.

In the second half against Dallas, though, Connie had a chance to redeem herself. Sent in to guard Lieberman, she took a charge and stole a pass. The bench roared. Kunzmann went on to lead the Wranglers with 19 points (she averaged 3.0 per game) and 10 rebounds. Even in defeat, Kirk praised her afterward. Lieberman, too, was impressed. “I remember driving down the middle and she was so strong that it was like hitting a wall,” she says. “Connie wasn’t flashy, but she was the player you needed on your team if you wanted to win.”

With the performance, Connie solidified her spot on the Wranglers. That Saturday night, still buzzing from the game, she headed out to her favorite sports bar in Omaha, Tiger Tom’s, to meet friends and celebrate. She was the type of person who could strike up a conversation with anyone over a beer, or three. She greeted strangers like friends and delighted in talking about the WBL. On many evenings like this, her roommate and teammate Genia Beasley came along. On this one, though, Beasley stayed in.

The next morning, Beasley noticed her friend hadn’t returned home. She figured Connie had stayed over with someone and would be back soon. It was only when she missed practice that Beasley, and others, began to worry.

Today, a young girl staring up at a poster of Candace Parker or Diana Taurasi on her bedroom wall wouldn’t think twice about a career as a pro basketball player. For her the WNBA, which just celebrated its 25th anniversary, has always existed. A talented teenager can play AAU ball, earn a college scholarship and, with the advent of new NIL rules, perhaps earn a little money on the way to a pro league with a $60,000 minimum salary.

Such opportunities would have been hard to fathom in Connie’s era. This was before Cheryl Miller scored 105 points in a high school game, before Lisa Leslie dunked her way onto ESPN highlights. UConn was not yet UConn, and Rebecca Lobo was in elementary school. The NBA, meanwhile, was emerging from its own tenuous period, with Finals games relegated to tape delay and rosters beset by substance use problems. College basketball was the more popular men’s game, and March Madness for women wouldn’t even begin until 1982. Plenty of high schools didn’t even have girls basketball programs.

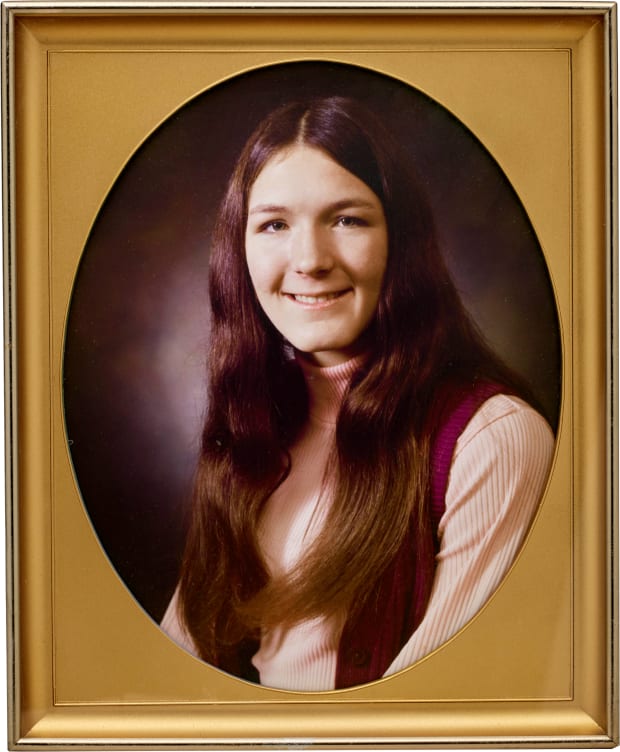

But Connie was fortunate: Of all the places for a basketball-loving girl to grow up in the 1970s, you’d have been hard-pressed to pick a better one than Everly. A town of 700 in Iowa’s northwest corner, Everly was known for corn, soybeans and hoops. The Everly High Cattlefeeders’ girls team was a local institution, winning a state title in 1966 and qualifying for the tourney almost every year for a decade. In Iowa, where girls teams routinely outdrew the boys and 15,000 fans packed Veterans Auditorium for the state tournament, this was a big deal.

Connie had grown up going to games with her father, Ray, who served in the Army Air Corps in World War II before settling into farming and raising cattle. She took after him: hardworking and competitive. But her world capsized at 13 when Ray died of a heart attack. That year she spent more time helping out on the farm. She also went out for the basketball team.

Back then, girls in Iowa still played six-on-six, with three “guards” on defense, three “forwards” on offense and neither unit allowed to cross half court. Strong and tough, Connie excelled on D and made the Cattlefeeders’ varsity as a freshman. Her senior year, switched to offense, she averaged 34 points and was all-state. Around town she was a celebrity; her younger brother, Rick, remembers people “always patting me on the back” just for being related to her. Later, on scholarship at Wayne State, Connie set a slew of school records, once pulling down 25 rebounds. “She kind of pitched her tent in the gymnasium,” Chuck Brewer, Wayne State’s coach, later told one writer. “Whatever you asked for, she always gave you more.”

Courtesy of the Everly Heritage Museum

Meanwhile, women’s basketball was slowly gaining in popularity. The sport had been around since 1892, when a Smith College physical education teacher named Sandra Berenson adapted James Naismith’s rules, creating the six-on-six format, outlawing steals and limiting players to three dribbles. But for almost another century the women’s game would be hindered by a lack of resources, Byzantine rules and antiquated and sexist views about women’s sports that limited opportunities. This all began to change in 1972, after the passage of Title IX, the landmark civil rights law that prohibited discrimination based on sex at any school that received federal funds.

Top college teams, like Immaculata, started drawing big crowds, as did the barnstorming All-American Redheads. After Billie Jean King’s televised defeat of Bobby Riggs in the 1973 Battle of the Sexes drew 90 million viewers worldwide, CBS greenlit a series of gender battles that included Redheads star Karen Logan facing the Lakers’ Jerry West in H-O-R-S-E. (Logan won.) And in ’76 the Olympics finally added a women’s tournament. (The men had been competing since ’36.)

Bill Byrne, for one, believed the time was ripe for a women’s pro league. Part huckster, part visionary, part b.s. artist, he had run a sporting goods store and then founded an NFL scouting service and a short-lived pro softball circuit. Impressed by ticket sales at women’s college games and hoping to get in early on the next big sports wave, Byrne vowed, one night over beers in 1977, to start a league. He recruited Logan (who designed the 28.5-inch women’s ball, today’s standard) as a player-coach and came up with the league name, which he marketed as the WBL, instead of WPBL, because it sounded more like the NBA and the NFL. Then, to lure investors, he set about making a bunch of promises about scope and reach and return—some of which he even kept.

It worked. Sort of. In the spring of 1978 the WBL held tryouts across the country, followed by a draft. A few of the biggest names taken, including future Hall of Famer Carol Blazejowski, chose to retain their amateur status for the ’80 Olympics. Plenty of other draftees had no idea the league even existed: One day they were making their postcollegiate plans, and the next a friend or relative told them they were part of the WBL.

That December the league launched a 34-game season with eight teams, four fewer than hoped. Franchises cost just $50,000 and player salaries could be as low as $3,000. (Kunzmann, after a tryout, signed with the Cornets for $7,500.)

The WBL did garner press, though. FEMALE PROS MAKE HISTORY, announced The New York Times. On the night of the league opener Walter Cronkite ran a four-minute report on the CBS Evening News. Then, in front of 7,824 fans, the Chicago Hustle beat the Milwaukee Does, one of a handful of teams (the Minnesota Fillies, the Dayton Rockettes . . . ) that bore awkward gendered names.

Much about the league felt makeshift. Teams traveled great distances by bus and occasionally played in high school gyms. Players stayed in cheap hotels, sometimes six to a room. Depending on the club, and the owner’s liquidity, a paycheck’s arrival could be more a matter of if than when. Franchises, which lost an average of $260,000 in that first season, launched and folded in the span of months.

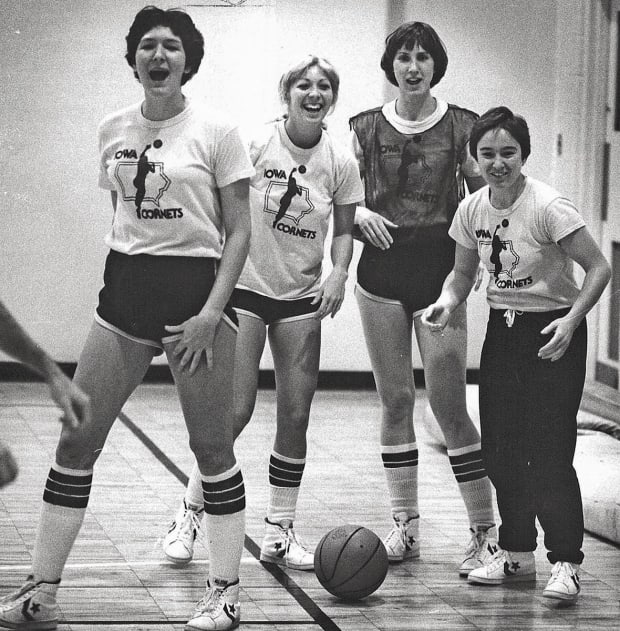

Connie, though, got lucky. Not only were the Cornets close to home, but they also were relatively flush, owned by George Nissen, a collegiate gymnastics champion who went on to invent the trampoline and start a sporting goods business. While other teams made do, Nissen handed out $100 bills at his Christmas party and bought a Greyhound team bus (dubbed the Corn Dog) that he outfitted with TVs, a refrigerator and a stereo system. On long rides, players slept on the carpeted luggage racks. Kunzmann and her teammates played cards, talked about Saturday Night Live and rocked out to AC/DC.

Courtesy of the Women's Basketball Hall of Fame

Right off the bat, Connie bonded with Bolin, the Cornets’ star guard, a fellow small-town Iowan who had gained renown—and the nickname “Machine Gun Molly”—for her deadeye jump shot. While Bolin led the Cornets (and later the WBL) in scoring, setting a league record with 55 points in one game, Kunzmann was a fan favorite. She averaged 11 points and 11 rebounds, and she led Iowa in steals. In photos you could see the bruises on her legs from diving for loose balls. She was the one who cracked up teammates by wearing Groucho Marx glasses or putting smiley faces on everything; the one who served champagne into plastic glasses after the Cornets made the finals their first season. She introduced herself, “Hi, I’m Connie Kunzmann and I play for the Iowa Cornets.” She kept a chalkboard in her room, on which she wrote inspirational maxims and she competed at everything, constantly playing a handheld electronic football game, the beeps of which Bolin can still recall to this day.

Connie and the Cornets won both because of and in spite of the men in charge. After hiring and firing three coaches before the first season, ownership settled on Kirk, who, like the majority of his WBL peers, had never before coached women. (Nearly all of the WBL’s coaches were male.)

Though players recall Kirk as a mostly effective tactician, he seemed lost when it came to relating to 21- and 22-year-old women. He tried to micromanage everything from the fast break to his players’ social lives, laying down a series of rules, with fines for breaking them. He prized discipline and motivated by criticizing. “He felt like he could coach us the same way he coached the men,” says Bolin. “He didn’t have a high level of tolerance.” (Kirk died in 2014 at age 71.)

When the team goofed around in the rear of the bus, Kirk would storm back and holler, “Get your game faces on!” Which, of course, never helped. It was, says Bolin, “like being in church and not being able to laugh.”

Banned from smoking or drinking, players would stash single-serving wine bottles from airplane trips and break them out in their hotel rooms. They held team parties, sang and performed skits, imitating their coach’s scowling demeanor. They gawked as they passed the strip clubs in New Orleans, marveled at the beaches in California and tried to sneak into Studio 54 in New York City, wearing their green satin team jackets.

Through all of this the Cornets flourished, racking up wins and leading the WBL in attendance two years in a row. But the league’s fortunes seesawed. Some teams, like Chicago, drew thousands of fans; others, hamstrung by poor leadership and a lack of promotion, drew crowds in the low hundreds. Byrne had expanded the WBL to 14 teams before the second season, and that stretched thin the talent and resources. Two franchises collapsed within the first 10 games.

When the league did receive press, the focus often wasn’t on the game. A 1981 story in Sports Illustrated centered on Bolin, who was pictured wearing a skintight leotard. The lede ended: “Suffice it to say that if beauty were a stat, Molly Bolin would be in the Hall of Fame.”

Meanwhile, players chafed at the league culture. According to former WBLers interviewed for this story, plenty of male coaches slept with at least one of their players, which led to favoritism, among other problems. Women say they were expected to look like sex symbols or to show up in pigtails, without makeup. Early on, Logan, one of the few players with leverage—she was the first woman to receive a Nike contract: $3,500 to endorse waffle running shoes—tried to lead a union drive. As a result, she says, she was blackballed, unable to find a team for the WBL’s second season. “The message was: Don’t come here, because we don’t want any trouble,” she says. “The power structure was male and certainly didn’t want women to unite and have any kind of voice.”

Des Moines Register/USA Today Network

By the end of the second season, the WBL was foundering, Iowa included. To publicize his team Nissen had poured $1 million into a movie called Dribble, an uncomfortable comedy, never released, that starred Pete Maravich alongside the Cornets. (The movie’s tasteless tagline: “A battle of the sexes . . . who’ll end up on top?”) Facing losses, Nissen divested most of his stake, and the next owner started bouncing checks. Even though they made the finals for a second time—falling to the New York Stars in the clinching Game 4, despite 20 points and 12 boards from Kunzmann—the Cornets folded that fall.

The players dispersed. Bolin headed to San Francisco, enticed by the chance to play for coach Dean Meminger (an NBA champion as a guard with the Knicks). She tried to recruit Connie and might have succeeded if not for the formation of the Wranglers, a new Omaha franchise, closer to home, where Kirk took the head coaching job.

To this day, Bolin wonders how things might have turned out if only she had persuaded her friend to join her.

Missing one practice was weird. But two? That was unheard of for Connie, especially since each absence came with a $50 fine.

Still, her older brother, Craig, tried to stay optimistic, even after their mother, Eleanor, called him on Feb. 9, 1981, to say that she had heard from a police sergeant in Omaha, and that Connie hadn’t been seen in more than a day. A handwritten missing persons report stated: “This person is a pro basketball player for the Wranglers. . . . She has never missed practice in the past like she has for the past two days.”

That night, Craig and Rick drove to Eleanor’s house. Craig did his best to comfort her. “Connie has always been able to handle herself,” he recalls saying.

Indeed, she had. She had settled into Omaha. The Wranglers were winning, fueled by the dominant post play of top draft pick Rosie Walker and the floor leadership of point guard Holly Warlick, both All-Stars that season.

Omahans had responded, thousands coming out to the Civic Auditorium on winter nights. Even so, the franchise struggled under the ownership of Larry Kozlicki, a Chicago tax attorney who, like many WBL stakeholders, knew little about basketball but enjoyed the publicity and hoped to cash in on the next big thing. Kozlicki had already run one team, the California Dreams, into the ground the previous season; players had walked out over months of unpaid salaries. (Perhaps it had to do with allocation of funds; Kozlicki reportedly enrolled the whole team in John Robert Powers charm school, where they learned how to apply makeup and walk runways.)

That Kozlicki got another chance is evidence of how desperate Byrne and the WBL had become. On the occasions when the Wranglers did get paid, it was often by personal check or cash in an envelope. Management forced players to wear Wrangler boots, cowboy hats, jeans and red-and-white checkered shirts when they traveled. (“Godawful,” says Beasley.) Sometimes, on the road, they had to hitchhike from the hotel to the arena because Kozlicki was too cheap, one player says, to pay for buses.

As in Iowa, Connie was the heart and soul of the team. Even though she came off the bench, she was named captain. “You could count on her,” says Warlick. “She was just a solid person.”

Courtesy of the Women's Basketball Hall of Fame

Not long after arriving, Connie had adopted Tiger Tom’s as her local hangout, always arriving in her yellow Mustang, with kunz license plates. She even wrangled a personal sponsorship from the pub, and for a while she dated one of the bartenders, Tom Christensen, who was surprised by how open and friendly she was. After meeting only once, she began writing him letters. “Connie was the most upbeat person I have ever known,” he later told Inside Sports. “She made you feel at ease.”

Connie wasn’t looking to settle down, though. In January 1981 she had gone to Tiger Tom’s to help promote the WBL, handing out free tickets, and she hit it off with Lance Tibke, a security guard at a nuclear power plant. At the time, the 25-year-old Tibke was either engaged or about to be. It seems unlikely, though, that he told this to Connie. That night, after hanging out over beers, the pair left together and spent the night at Kunzmann’s place.

They didn’t see each other again until late in the evening of Feb. 6, when Tibke dropped off his fiancé at her house and then swung by Tiger Tom’s a little after midnight. Spotting Connie leaving the bar in her satin green Wranglers jacket, he pulled over.

She said she was headed out to meet friends at an all-night diner. Tibke offered to give her a ride.

Even 40 years later, the details of what happened next are difficult to relay.

Connie got in the car and Tibke drove toward a quiet, private area, turning down a gravel road beside a cemetery and parking where they had a view of Omaha, lit up at night. Tibke later told police that he intended to have sex with Kunzmann, but precisely what occurred remains unclear. He would say that he felt guilty and backed off, angering Connie. Those who know her, though, doubt this. They think it’s far more likely she was the one who said no.

One thing is clear: Tibke snapped. He attacked Connie with a pocketknife, then grabbed a tire iron that he kept under his seat, hitting her “five or six times” in the head, according to his police statement.

Connie fought back. Friends and family take a sliver of comfort in the fact that Tibke was left bruised and battered in the end. “She didn’t go down easy,” says Warlick. “That guy had scratches on his face. She fought to the end.”

At some point Tibke realized that Kunzmann was dead. Panicking, he buried her jacket and wallet in the cemetery and drove to Dodge Park, along the Missouri River, where he backed his truck up to the icy water, lugged out Connie’s body and then let the current take her away.

At 4:30 a.m. on Feb. 10, three days later, Tibke, at the urging of his father, arrived at the Omaha police department and confessed to the murder.

The weeks that followed remain a blur for those who loved Connie. Eleanor proved inconsolable; when her sons came to tell her of the confession, she “just kept saying, ‘No, no, no,’ ” according to Craig. Friends and teammates were crushed. Since the police hadn’t yet found a body, some clung to hope that Connie was still alive.

“Just disbelief,” says Warlick. “You kind of think she’s going to come through the door any second.” Beasley still vividly remembers small details, such as how, when police officers finally arrived at their apartment two days after Connie’s disappearance, her game-worn uniform remained damp with sweat in her bag.

Those looking for an explanation found none. Tibke had neither an obvious motive nor a history of violence. He had no criminal record—“hadn’t even gotten a parking ticket,” says Craig. When Tibke spoke about it, a year later for a story in Inside Sports, he provided no reasoning. “I couldn’t control it,” he said. “I began to pound her and pound her and pound her. She said, ‘Stop it, stop it, stop it. Please don’t.’ But I couldn’t stop. I don’t know why.”

As the community grieved, national media picked up the story. FEMALE BASKETBALL PLAYER MISSING AND BELIEVED SLAIN, ran The New York Times headline; A DEATH STUNS THE WBL, wrote The Washington Post.

The Wranglers postponed their game that week and, after a team meeting, decided to wear black armbands the rest of the season. They released a statement that began: “Connie was more than our teammate. Connie was a member of our family. In any situation, in any game, in any relationship, she gave more than she had to get. . . . Never did you hear her complain about her position on the team or in life. . . . People like Connie do not come along every day. . . . Her memory will remain with us forever. Her life will become ours. We will live and play as Connie would have, as Connie would want us to do.”

Seven weeks after the murder, on March 28, two boys fishing along the banks of the half-frozen Missouri spotted Connie’s body in the water. An autopsy determined the cause of death as “blunt force trauma,” from the tire iron. Tibke would be convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 40 years. Slowly, and then all at once, the finality sank in for relatives

and teammates.

Everly is not an easy place to get to, and the Kunzmanns didn’t know how many mourners to expect at Connie’s funeral. But friends—from childhood, from college, from the WBL—kept arriving. The church balcony filled, then the chapel, then the basement. Craig recalls little about that terrible time, but he can still picture the funeral and the outpouring of people whose lives his sister had touched.

That April, the Wranglers’ season came to a bittersweet end. They finished atop the standings and swept the Hustle in the semis to set up a best-of-five showdown against Lieberman and the Diamonds. It should have been reason to celebrate, the reward for all the hard work. Instead, players grieved . . . and worried about their futures. They reportedly hadn’t been paid in months and considered walking out, as the Hustle and the Fillies had a month earlier. But they wondered what that would accomplish. “You can’t boycott, because there’s no money,” says Warlick, who estimates that she received about half her salary that season. “You can’t sue them; they’ll go bankrupt. So we decided to play it out.”

At least the finals provided a thrilling showcase. Walker and Lieberman each averaged more than 30 points. Seven thousand fans showed up for each game at Moody Coliseum in Dallas, and 3,500 in Omaha. During the series, the league awarded the Connie Kunzmann Hustle and Harmony Award, honoring a player, New Orleans Pride captain Sybil Blalock, who personified Connie’s attitude and spirit. To watch the surviving footage of that series—a bit shaky, filmed by someone in the stands—is to get a glimpse of what the WBL might have been. The crowd, men and women and kids of all colors, in suits and in bellbottoms, is raucous. The players move with pace, nailing midrange jumpers, pressing on defense and, in Lieberman’s case, whipping one-handed passes.

On April 20, 1981, in what would be the WBL finale, the Wranglers beat the Diamonds 99–91 to take Game 5, and the title. Had Connie lived, she would have become not only a champion but also the only player in league history to make all three finals.

When the end came, the WBL went out with a whimper. No confetti fell after the clinching game in Dallas. “We didn’t even have a party,” says Beasley. Most of the players were too preoccupied with how they would find a way home after the season.

That fall the WBL finally, officially disbanded. And while the ensuing decades were littered with well-meaning attempts to start new leagues—the WABA, NWBA, WBA, ABL and the regrettable LPBA, with its 9' 2" basket and skimpy leotards—none lasted more than a few years.

Finally, in June 1997, the inaugural WNBA season tipped off with eight teams. New heroes arose—Leslie and Sheryl Swoopes and Cynthia Cooper. The league had its ups and downs but survived and ultimately thrived, providing a measure of stability in the women’s professional game.

The original WBL players went on with their lives. Many became coaches. Others became biochemists, college professors, athletic administrators, doctors, businesswomen, lawyers and real estate agents; wives and mothers. Many lost touch with one another and the world moved on.

While the NBA has gone to great lengths to venerate its foundational stars, the women’s game doesn’t display the same institutional memory. As a result, the saga of Connie Kunzmann and her fellow trailblazers has been increasingly lost to time, preserved only in faded game programs, grainy VHS tapes and the memories of those who lived through the WBL. The best feature written about Connie at the time, by Ira Berkow for Inside Sports—an article that was instrumental in piecing together the story you’re currently reading—isn’t online. When Nissen died, in 1996, his 800-word New York Times obituary didn’t even mention the Cornets. The only book about the league, Mad Seasons (another valuable resource for this story), was written as a labor of love by Karra Porter, a Salt Lake City lawyer who represented women’s players, and published by a university press in 2006.

And so it seemed that, as coaches and players moved on or passed away, all memory of the league threatened to go with them. That is: until 2018, when a group of alums, led by former New Jersey Gems shooting guard Ann Meyers and Hustle coach Doug Bruno, lobbied and pushed and pestered the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame long and hard enough. That June, more than 100 of the original WBL players walked onto a stage in Knoxville, Tenn.

There was Warlick, now an assistant at Tennessee. And then Notre Dame coach Muffet McGraw. And Lieberman, the most famous WBL alum, who’d gone on to become a WNBA coach and the first female NBA assistant, with the Kings. And, in a bright blue dress, there stood Bolin. (She now goes by Molly Kazmer.) The WBL’s all-time leading scorer (25.4 points per game) played briefly in the WBA and the LPBA, and she even shot a Spalding commercial with Larry Bird. She joined her peers, signing autographs for fans and laughing about old rivalries. That afternoon, the museum enshrined every WBL player into its Trailblazers of the Game wing, where Connie’s uniform is featured prominently. Now, any young girl or boy who comes can read about WBL stars, right alongside presentations on Pat Summitt and Dawn Staley.

Only a fraction of the history is there, of course, and it captures mostly the good stuff. Those who played in the WBL readily acknowledge its flaws. Though the league was intended to be a progressive venture, too many of those in power were men motivated not by progress but by entrepreneurial dreams, or having a franchise of their own to brag about. Plenty who played wonder what their lives would have been like if only they were born a decade or two later. Just imagine the endorsement opportunities for players like Lieberman or Walker or Bolin, who says, “Everybody knew that women’s basketball was going to make it. We just didn’t know when.”

Bolin in particular suffered due to the chauvinistic attitudes of her era. When she and her first husband divorced, after the WBL folded, she lost custody of their young son, based in part on the argument that, as a professional basketball player, her travel and promotional duties had made her an unfit parent. (A year later, the Iowa Supreme Court overturned that decision and gave Bolin full custody.) Teams, meanwhile, profited off her looks, once posing her for a swimsuit poster. But when Bolin decided to take control of her image and sell her own posters, to add to her paltry $6,000 team salary, press and management criticized her. “What I did was super conservative, as far as the cheesecake photos and marketing and promotions—but it was such a big deal,” she says. “Now, nobody would even blink at it. Not only that, I might have a million followers on Instagram.”

Some, like Logan, look back on that part of their lives as a painful period. They believe that pain makes it all the more important that they preserve the whole history, so others can learn from it. “I’m not trying to be old and bitter; I want to be authentic and honest,” Logan says. “Ours is the story of the struggle for women’s basketball to get off the ground. The struggle has some not-so-nice parts to it, and some nice parts.”

In this way, the story of Connie Kunzmann’s death is inextricably tied to the WBL, its darkest moment. It’s also a marker of the league’s struggles. After years of courting the country’s press, the most attention the WBL received after its founding came not when its players thrived, but when one was murdered. (Decades later, it’s part of why this story is being told.)

Maybe that can change, though. Elizabeth Galloway-McQuitter, a defensive specialist on the Hustle who went on to coach high school and college for 28 years, was sick of hearing people refer to the WNBA as the first professional women’s league. She kept asking: “Whose responsibility is it to tell the history?”

Fed up, she decided it was hers. So, after the Hall of Fame ceremony, she and a group of WBL players founded a nonprofit, Legends of the Ball, geared toward raising awareness of the league. Galloway-McQuitter organized meetups, wrote a mission statement and, to inspire her peers, quoted Maya Angelou: “How important it is for us to recognize and celebrate our heroes and she-roes!”

Now, as Title IX nears its 50th anniversary and the WNBA moves into its next quarter century, there is talk of a documentary, maybe even a scripted TV series, like GLOW for basketball. Galloway-McQuitter aims even higher, hoping for a permanent display in the women’s Hall of Fame. And induction into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. And then the Smithsonian.

Bolin just wishes her friend was here to be part of it.

Like so many small farm towns in the Midwest, times haven’t been easy of late in Everly. In 2019, the middle school and the high school shuttered, taking with them the Cattlefeeder legacy.

That’s why it was so exciting for the Kunzmann family when the Everly Heritage Museum opened its doors last fall. Sure, it’s just one room in a community center on Main Street, and it’s open only two days a week, by appointment. But that doesn’t matter to Craig and Rick. What matters is that Connie has her own display, with photos, plaques, news stories, trophies and her yellow WBL travel bag.

For the most part, the Kunzmanns have left Everly. A bunch of relatives headed to the West Coast. Rick is in South Dakota. But Craig is still in town, where he co-owns a construction business. Eleanor died in 1993. “She never quite got over Connie’s death,” says Craig. “Like part of her was gone.” It particularly vexed Eleanor that Tibke served only nine years of his 40-year sentence, getting paroled in ’90. “She wanted to go after him and put him away for as long as she could. I said it wasn’t worth putting yourself through that.”

Those who knew Connie wonder now how her life might have played out. Warlick thinks she may have gone back and worked on her parents’ farm, adding, “She would have been a good coach, too. She’d have had a family and a bunch of kids by now; I’m positive about it.”

Courtesy of Molly Kazmer

Craig and Rick agree that she’d be coaching. “I think she’d be there, supporting some kids who were saying, ‘I don’t think I can do this,’ ” Craig imagines. “She’d say, ‘Yes, you can. I know you can. I did, and I know you can do it, too.’ She’d be right there, pushing, not getting upset.”

On occasion Rick still hears from his sister’s teammates. Tanya Crevier, a guard on the Cornets, once came into the auto shop where he worked. Bolin recently sent him some old photos. She hopes that people remember Kunzmann not just for how she died, but for how she lived.

In Everly, people still know Connie’s name. As Craig points out: “It’s a small town, and people here don’t move much. Most of them know me.”

Outside of town, largely, it’s different. Still, every once in a while, out of the blue, Craig says someone will hear his last name and pause for a second. “They’ll say, ‘Kunzmann? I think there was a girl who played for the Cornets with the name. Any relation?’ ”

• Michael Jordan’s Final Reveal

• Inside the Life of a 7'6" Shot Blocker, Paralyzed in a Bike Crash

• Coach K: The Ultimate Team Builder